Slocan Valley paraglider Benjamin Jordan describes his record-breaking journey from Mexico to Canada and the resultant butterfly effect.

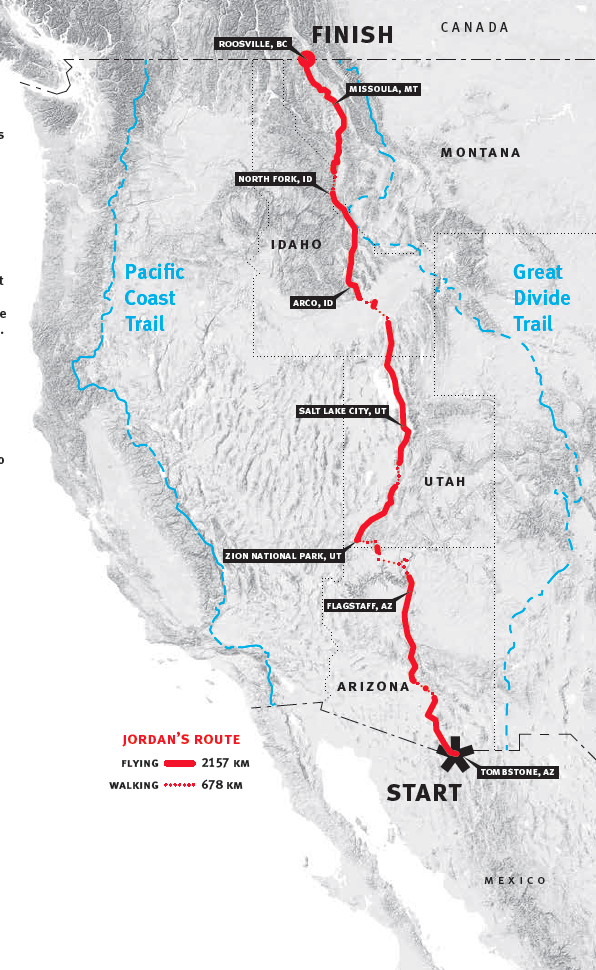

Inspired by the epic migration of the monarch butterfly, Slocan Valley, British Columbia, resident Benjamin Jordan recently completed the first-ever paragliding journey from Mexico to Canada, setting a world distance record. Over the 150-day trip, he covered 2,835 kilometres, spending 2,157 kilometres in the sky and 678 kilometres walking between launch sites. During his odyssey, he subsisted mostly on peanut butter, and finding drinking water was a constant concern. But Jordan persevered, living his dream on wind and a wing. Below are photos from the epic, the Fly Monarca film trailer, and what he endured, in his own words.

My trip started on April 8, 2020, south of Sierra Vista, Arizona, at the Mexico border, and it ended on September 4 at Roosville, British Columbia, a border town just north of Montana. During those five months I saw some dramatic landscapes, from towering peaks in Utah, Montana, and Idaho to the scorched earth and deep valleys of Arizona, including the deepest valley of all, the Grand Canyon. In total, I covered 2,835 kilometres, which is about the average distance monarch butterflies travel during their migration from Canada to Mexico, although eastern populations starting their journey from the north shores of Lake Ontario and Lake Erie can travel as far as 5,000 kilometres.

To launch from high ground, I often had to hike, which wasn’t easy considering I was carrying 14 days’ worth of food and 13 litres of water and my pack weighed 45 kilograms. My gear consisted of a tent, a sleeping bag and pad, a Jetboil stove and fuel, water bladders, a headlamp, camera gear, solar chargers, InReach satellite communicator, cellphone, clothing, first-aid kit, repair kit, passport, toothbrush, and my paragliding equipment. I also carried a small banjo, which was invaluable during those long stretches when I had to wait for good weather. It was worth the extra kilogram.

I began my journey at a section of the infamous border wall separating the United States from Mexico. Border patrol vehicles were constantly driving past me, and I had to explain myself to an officer multiple times. About 300 kilometres south of this spot is a high-altitude oyamel fir forest, one of only 12 in Mexico, where monarchs overwinter. The butterflies prefer these zones because they’re moist and cool—but not too cold, as monarchs become paralyzed in temperatures below 4°C—while the rest of the region is hot and dry.

The monarch is the only insect on Earth that performs this annual epic two-way migration, and scientists are still unsure how it manages this. One theory is that a small quantity of magnetite in their bodies acts as a kind of compass that leads them to the magnetic iron found in their wintering grounds. To learn more about migration patterns, the non-profit Monarch Watch has developed featherweight stickers that affix to monarchs’ wings. Citizens can note the date and place where they discover the butterfly’s body and upload the information to the organization’s website.

Scientific data collected by the World Wildlife Fund found that monarch populations wintering in Mexico had decreased by 60 per cent in 2019 compared to the mid-1990s. Industrial farming is thought to be one cause of their decline, as herbicides kill milkweed, the sole food of monarch larvae. The monarch butterfly is now a candidate under the US Endangered Species Act, and associations such as Monarch Watch offer free milkweed seeds for schools and non-profits to plant in an attempt to curb the monarch’s decline.

As with any adventure, I encountered hazards, including gun-toting landowners wary of trespassers. Luckily, these three folks I met in North Fork, Idaho, were friendly. The fall-out from the COVID-19 pandemic wasn’t much of a concern because I was alone most of the time, but it did cause some anxiety when I tried to restock at various grocery stores and their shelves were almost empty.

My biggest hardship was finding water during the first half of the trip when I was in arid environs. At one point, east of Phoenix, Arizona, I had to settle for filtering water from a puddle of sludge. Another challenge was wildfire. California was experiencing its worst fire season in history, and the smoke wafted as far east as Europe. I was 50 kilometres south of the Canadian border when I took this picture, and I had to hike high above the smoke to gain visibility.

I subsisted mostly on peanut butter spooned from plastic bags during the five-month odyssey, so for my sixty-ninth and final flight, I splurged. I ordered a pizza in Whitefish, Montana, and ate it while flying north of the appropriately named town of Eureka, where my journey ended at the British Columbia border.

I became interested in paragliding after being evicted from my apartment in Toronto. I was crashing on my cousin’s couch when I saw a paraglider on TV. I was immediately intrigued, but a voice in my head said, “You can’t do that” and then it listed all the reasons why. I eventually realized I was simply afraid, so I signed up for a course and fell in love the second I was airborne. The first thing I learned is that paragliders are always flying down. The trick is to emulate butterflies and birds of prey by finding air that’s rising faster than you are descending, which happens once the sun heats the Earth and certain areas release that heat. A good trick is to imagine turning the landscape upside down: features water would drip from—think summits, spines, and buttes—often act as triggers where heat rises and paragliders will find lift.

Sometimes you can’t find pockets of rising air and you’re forced to land. Ideally, you’ll navigate to a ridgeline or another elevated area before touching down, but a lot of times it doesn’t work that way and you’re faced with a long, hot slog back up again. In this photo, I’m northeast of the Grand Canyon, and because paragliders aren’t legally allowed to launch in national parks, I had to hike 210 kilometres. I love flying, but sometimes you just have to walk.

This story first appeared in Kootenay Mountain Culture Magazine #39. Benjamin Jordan is an award-winning filmmaker. His movie about his world-record journey from Mexico to Canada is called Fly Monarca and can be viewed at flymonarca.com.

Related Stories

Surf Canada Now Ranked Top 10 In The World

Thanks to an historic showing at the World Surfing Games in Japan, the Surf Canada team is now ranked 10th overall in…

Her Highness: Mia Noblet Sets Yet Another World Highline Record

From Brazil to China to Norway, British Columbia highliner Mia Noblet has spent this past year walking her way into the…

How One Man Broke a World Record Paragliding The Rockies

Talk about tales from the gripped. Paraglider Benjamin Jordan shares his first-hand reports from a record-breaking…

KAVU Canada Lands First in Fernie

On March 22, 2014 KAVU & Elevation Showcase Presents KAVU Canada. KAVU athletes and KAVU staff will be dropping…

The Craziest Rope Swing in The World

Oh. My. God. This is absolutely terrifying. The look on their faces tells you just how terrifying it must have…

2012 Freeskiing and Freeride World Tour

2012 Freeskiing and Freeride World Tour was in Revelstoke BC on Jan 4-11. Mens Results, -Canadian Kye Petersen took…