For centuries they have been cast as evil incarnate by history’s cruel puritans and Hollywood’s horror genre. But from the Okanagan to Northern Montana, and around the world, witches exist not to spook nor hex, but to enlighten and empower. By Clare Menzel

I am late for the sabbat. Speeding into town, I blow past the signs promoting the First Baptist, Lutheran, Christian, Pentecostal, Roman Catholic, Anglican, Gospel Chapel, United, Seventh-Day Adventist, Russian Orthodox, and Baptist churches of Grand Forks, British Columbia. “Everyone welcome,” one sign says. I park outside the white two-storey home with a bronze van in the driveway and a chalkboard sign on the porch that says “tarot cards.” There is movement in the temple, obscured by stained-glass bay windows. Before I can knock, High Priest Lord Lunar Wolf opens the door to greet me. Underneath his long-hooded robe, he wears fleece pyjama pants patterned with pool balls, a sheath for a ceremonial blade, and a T-shirt screen-printed with a pentagram, the protective five-pointed star, which must surely bewilder members at those other holy places in Grand Forks.

Inside, his wife, Lady Morgana Spier, who is high priestess of the nine-person Sacred Moon Coven, is beginning her closing blessing of the sabbat, one of eight pagan holidays celebrating the procession of seasons—think May Day and Yule. She also has a robe on, cornflower-blue Crocs, and a palm-sized Dalmatian jasper pendant for clarity and calmness. “Mother Goddess,” she starts, “the source of lice….” She chokes back a laugh. The other robed witches, who stand in a circle holding hands around the altar table, giggle. Children of all ages, including Lady Morgana’s great granddaughter, look on. “The source of life,” she corrects herself, and then concludes the blessing by inviting any listening gods or goddesses to stay and enjoy the afternoon festival.

Polytheism—the worshipping of more than one deity—is perhaps the single universally shared value of paganism, which is the broadest category used to describe non-Abrahamic (non-Christian, non-Islamic, non-Judaic) Western spirituality. Witchcraft is a strain of paganism. Many witches worship at least a dual goddess and god; many worship figures from one or more pantheon. Even if practitioners worship only one goddess, they will at least validate other deities, including the Christian God.

Think of witchcraft like a choose-your-own-adventure book. Every witch’s path is his or her own bespoke expression of a relationship with the divine. Witches reject commonly held dogmas and authority figures. The “craft” is simply the practice of magic, which ranges from everyday folk herbalism to high ceremonial rituals conducted inside a sacred circle. Many witches follow particular pre-Christian Northern European traditions. Others pull from worldwide cultures, tweaking and melding different aspects of them. Certain sects accept a natural law of retribution similar to karma. Most witches agree on the principle, “do what ye will, yet harm none.” For many, this rules out spellwork cast upon others, a violation of their free will.

Ethics aside, the most effective way to change circumstances, witches have found, is to bend their own perspectives. It’s something like attracting a lover by building your own confidence. Or quitting bad habits and watching toxic people drift away. At its best, this spiritual work cultivates accountability, concentrates willpower, and can lead to radical self-transformation.

Lady Morgana, whose everyday name is Mitch Regnier, grew up with these ideas. Her maternal grandmother spent a sheltered but whimsical childhood in a Danish windmill, offering honey to faeries and collecting herbs on edelweiss-covered hills. Regnier also told me about two great-aunts who were killed for their work as healers. When the family fled to British Columbia in the 1950s to escape the Gestapo, it brought its spirituality. Regnier met Lord Lunar Wolf, whose everyday name is Wayne TK, more than 40 years ago, as kids in Vernon. Their parents were in the same coven, the name for a group of witches whose paths run parallel and intertwine. Together as teens, they discovered Wicca, an English sect that codified witchcraft theology in the mid-20th century. They formed their own coven. Now in their fifties, they travel the summer festival circuit selling divination services, tinctures, and other wares. One top seller is a “vanishing spray” Regnier makes with mugwort, lavender, and a tiny white quartz crystal—her mom’s recipe. It’s for children who are afraid of monsters. Even if it doesn’t “work” in the mundane sense, “it gives a child their power back,” Regnier says. That’s witchcraft.

One top seller is a “vanishing spray” Regnier makes with mugwort, lavender, and a tiny white quartz crystal—her mom’s recipe. It’s for children who are afraid of monsters. Even if it doesn’t “work” in the mundane sense, “it gives a child their power back,” Regnier says. That’s witchcraft.

Witchcraft is so self-defining and anti-authoritarian that it’s hard for the general public to pin it down. Add in myths about cat sacrifices from “Hollyweird,” as Regnier calls it, and there’s legitimate concern about judgement, discrimination, or persecution. The earliest recorded laws stipulating punishment for malevolent spellwork and supernatural communion date back to ancient Egypt and Babylonia. But witch trials really kicked off in early modern Europe, with the spread of Christianity and fictions of devil-worshippers ready-made to justify the organized killings of social scapegoats. Related deaths from this period are estimated between 40,000 and more than one million.

The 16th-century witch trials of Puritan colonial America, known for their mass hysteria and moral panic, led to the murders of 20 people. More than once during my research, I was warned of modern-day witch hunters. In September 2017, experts gathered for a United Nations workshop correlated misunderstandings of witchcraft with ongoing “appalling” and “serious” violations of human rights—including ostracization, mutilation, and violent vigilante murder—in all regions of the world.

The modern revival of witchcraft is commonly traced to the mid-20th century and the repeal of European legislation criminalizing witchcraft. Stateside, it spread from the eastern seaboard to the Pacific coast, before reaching Canada. Regnier thinks the free love, free choice, “free this, free that” movement of the 1960s created fertile ground for the craft to blossom. “Even though it [the movement] wasn’t designated for witchcraft,” she explains, “I think witchcraft squeezed through that open door.”

Regnier estimates there are easily thousands of practicing witches in the Kootenays, and even more pagans, as well as people who don’t use these words but embrace similar nature-based spiritualities. She doesn’t see witchcraft dying, not at all. These days, you can meet witches on Facebook and learn how to do spells on YouTube. “I see it getting better and better,” she tells me. “More people are coming out of the closet. It’s like going to a dance and the dance floor is empty. You’ve got to start waltzing, and everybody will follow.”

I MEET TRACI SAVEL in Kelowna, British Columbia, on a Sunday at the women-owned barbershop where she does nails and reads tarot cards. Her powder-blue Volkswagen bug is parked right outside. She looks the part of a witch, with vibrant shoulder-length red hair and a flowy black outfit.

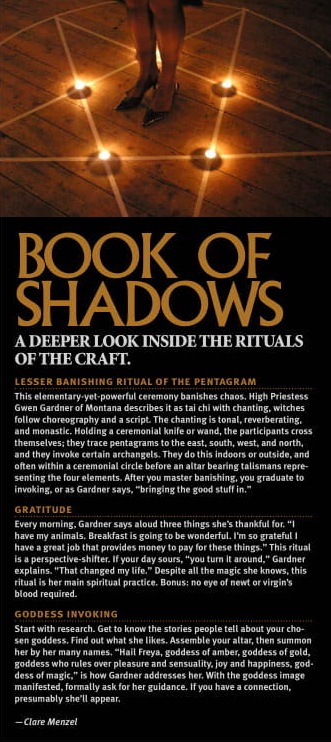

“I’m into dark stuff: blood sorcery, poison plants,” she tells me almost immediately. “Tea?” Savel puts the kettle on. As I select a bag of green tea, she pulls out her book of shadows, where a witch records rituals, recipes, and notes. She makes one every month, and eventually burns them. “I don’t show a lot of people,” she says. Shadow books are like scrapbooks stuffed with writing, art, tokens, and calendar pages. Each day’s entry is punctuated with a roundish, rusty-red mark.

Savel explains how, nearly every morning, she plucks a thorn from the bearberry bush in her yard, pricks her skin, stamps the book with a pea-sized drop of blood, and burns the thorn with a candle. She’s done this for so long, she can’t remember how she started. Her version of witchcraft isn’t populated with deities—her blood is the sacred force. She believes that drawing it, in symbolic amounts, helps to release any darkness inside and manifest her metaphysical intentions in the bodily world.

Gardner’s practice these days is invoking Freya, or opening herself for Freya to literally enter her physical being. She describes it as being “downloaded” with the spirit. This is worship for witches.

Using her own blood also connects Savel to her ancestors, who were Welsh herbal healers. An essential practice of hers is necromancy, or communing with the dead. “I wake up everyday asking for their guidance,” she says. “It takes a village, regardless of if the village is alive or not.” She often practices at a graveyard in Kelowna, favouring pitch-black new-moon nights because they represent gestation. She doesn’t participate in a coven, despite living among some 2,000 to 5,000 witches in the Okanagan Valley—her estimate, as an organizer of the local Pagan Pride. In her view, communal witchcraft is more susceptible to dogma and rules and structure. “I’d go to church if that was the point,” she jokes. She also thinks mainstream witchcraft’s aversion to hex work is unrealistic, even a bit fluffy. “If you harm me in any way, you are going to get screwed,” she warns. “That’s where the darkness comes in. Humans aren’t creatures of logic. We’re emotional.”

After I page through her shadow books, Savel takes me to the Mission Creek Greenway, five minutes from her childhood home. Walking toward the trailhead, she notes small bunches of catnip and stinging nettle encroaching on the gravel parking lot. There’s usually more, she says, but they mowed it down recently. Nearly year-round, Savel forages in Kelowna for plants to make teas, tinctures, and other medicines. She prefers to stick within what she calls her four-block radius, to maintain a close relationship to the land. After harvesting, she sprinkles a homemade mixture of dried blood, tobacco, and used tea over the plants. It’s another way to connect. Every existing thing has a soul, she says, whether it’s a person, a pebble, or a plant. In witchcraft, this belief is called animism. Depending on the season, Savel can spend 10 hours outside harvesting. She usually works alone. Sometimes she brings her pet bearded dragon.

I ask Savel to show me someplace significant to her practice. She leads me under a leaning ponderosa pine, through a hallway of yellow aspen, and into a cedar grove by the creek. The 48-year-old is fashionable, well-coiffed, but, while I wouldn’t have picked soft-soled ballet flats for trail travel, she doesn’t look out of place here. The bond she’s cultivated is palpable. She points out a mossy stump she’s used as an altar, as well as rune symbols carved into bark. An existing pit is suitable for fire offerings; the creek provides water to conclude rituals. She also comes here to meditate. The cedars seem to have the presence of female ancestors, she says. In silence, we stare into the rushing creek.

BY EMAIL I ASK LADY GWEN Gardner, high priestess of northwest Montana’s Garden Crescent Moon Coven, to show me what it looks like to commune with a goddess. She demurs, saying it would be like inviting a stranger into a therapy session. But she offers to show me her altar to the Norse Goddess Freya, so I drive to her home just outside Kalispell, Montana, on a clear, sunny afternoon. Gardner, 50, is petite and has straight brown bangs. She meets me outside. She wears a raspberry-red tie-dye shirt, neatly applied eyeliner, and a silver anklet with pentagram charms. She blushes as her many dogs and cats swarm, begging for pets, but she doesn’t shoo them away.

Her coven isn’t of any particular tradition. “Early on, we realized we have to be eclectic,” Gardner explains. “There’s not that many people here…. In a big city, you can have a tiny coven of the Immaculate Circle and everyone is the perfect witch. We can’t be cliquish here.” Membership has fluctuated, from 15 at times to two—just Gardner and High Priest Lord Shawn Forsyth. Now, there are five serious members. There are more in the “outer grove,” people who come to events but aren’t enrolled in the formal classes Gardner teaches. The coven’s Facebook group, in which Gardner posts funny memes, event notices, and inspirational quotes, has more than 230 members. Turnout to Pagan Pride varies, and Gardner suspects most attendees would not call themselves witches. Still, she hints that it’s no minor success to be spiritual, but not Christian, in Trump country. Among certain crowds, Gardner says, “I don’t not talk about it, but I don’t bring it up.”

She tells me about how, after growing up Catholic, she encountered witchcraft in a college “her-story” course. The empowerment was tantalizing. “I’m not a victim,” she learned. “I am a witch. I create and I do. I make things happen. I’m in control of my world. I haven’t given my power up.” She honed her skills in increasingly advanced ceremonial rituals, complete with ancient languages and intricate choreography. When she sought a higher power, she called on earth, fire, water, and air.

Then, after nearly three decades of spellwork, she found Goddess. “It was funny, I felt like a Christian,” she says. “What we find is what they find: a deity that connects. It’s joyful.” Gardner believes that there is a universal goddess, but also that it’s hard to fathom something so powerful and infinite. Everything that exists derives from this energy—not only humans but also thousands of goddesses, who Gardner sees as accessible archetypes representing every facet of life. When Gardner got divorced, her instinct was to close off entire parts of herself. “I was putting off dealing with goddesses of sexuality, but then I realized, that’s crippling. I had to explore that.” So, with an affinity for the Norse pantheon, she sought out Freya, the goddess of love, sex, beauty, and war.

Gardner’s practice these days is invoking Freya, or opening herself for Freya to literally enter her physical being. She describes it as being “downloaded” with the spirit. This is worship for witches. Gardner might chit-chat, offer gratitude, seek healing, ask a question, or meditate in silence. Sometimes she’ll share a cup of tea and a snack, or play music. Another deity Gardner worked with demanded tobacco, which she dutifully left, unlit, on the altar. She’s not a smoker. Her altar to Freya, arranged on a small circular table, includes rose potpourri, golden amber, and a falcon feather.

“I’m into dark stuff: blood sorcery, poison plants,” she tells me almost immediately. “Tea?” Savel puts the kettle on. As I select a bag of green tea, she pulls out her book of shadows, where a witch records rituals, recipes, and notes. She makes one every month, and eventually burns them.

After months of communication with Freya, the goddess arrived unannounced during a sabbat. Gardner used to be a dancer, but arthritis keeps her on the sidelines during bonfires. She was drumming, when she felt a sudden urge to dance. “All of a sudden, I’m floating and I’m just flying and leaping and twirling, and my skirt is going and I’m on fire,” she says. “I just. Feel. Beautiful.” The next morning, a stranger told her that she’d seen Freya whirling around the bonfire, ten feet tall and with a head of flames. That’s exactly how Gardner had felt.

NOT LONG AFTER REGNIER’S ceremonial sabbat blessing at the Sacred Moon Coven in Grand Forks, the potluck commences: spiced chicken, quinoa, potato salad. Dessert is served simultaneously. While eating, Wayne TK s Tummarizes the historical sci-fi fantasy self-help book he’s writing. Within 10 minutes, we are deep in a discussion about free will and alien overlords. He also seems pleased to have a new audience for his punny jokes. When he asks me, “Where does happiness come from?” I think he is setting up another punchline. But he just says, “Within,” and turns away.

I sit down in the temple next to Dani Gulietta, a young witch with champagne-blonde hair who is new to the coven. She grew up “Amish Christian,” she says, in a home she describes as strict and destructive. Even when speaking about childhood trauma and mental disorders, she is upbeat in a way that makes me think she’s gaining confidence in her mastery over that part of her life. Therapy and medication are crucial. So is witchcraft: she began exploring the craft on her own at age nine. Now she has Wicca stickers on her locker at high school. Her grandmother still leaves Bibles in her room, held open with a crucifix, to pointedly particular pages.

When most of the children go to bed, Regnier regales me and Gulietta with tales of backfired spellwork, egos destroying covens, and the time a woman’s pubic hair caught on fire during a ceremony performed “skyclad,” or nude. Amid discussion of building a bonfire, Gulietta’s grandfather arrives on pickup duty. He waits outside. When darkness falls, Regnier curls up for the night on a couch in the temple. She likes to sleep in there, she tells me. The next morning, though overcast, dappled light shines through the stained-glass windows into this house of Goddess.

Related Stories

Take Part in the Smart Kootenays Challenge

Columbia Basin communities are looking for your input on how to make the region’s coveted lifestyles even more…

Merry Christmas People

We here at Kootenay Mountain Culture Magazine would like to put out a big giant snow filled hug to everyone who's been…

A New Book Offers Up Amazing Old Photos of the Kootenays

The recently released Lost Kootenays book provides a glimpse back at a simpler time in the region, when things were…

Alien Encounters in the Kootenays

From audio anomalies to celestial orbs, there is no shortage of Kootenay UFO sightings. Are they hallucinations?…

Fly-Fishing in the East Kootenays

After a couple of bad breaks, an upstart East Kootenay angler learns the river's ropes and finds revival in the…

Singletrack 6 Race To Visit West Kootenays for the First Time

Singletrack 6, a mountain bike event that runs over six days in various communities in Western Canada, is coming to…