They lie underfoot and on tree branches, the tops of old fence posts, and way up high on alpine rock. Built not of one organism but a symbiosis of two, lichens are a fascinating natural phenomena, one Trevor Goward has dedicated his life to. In the woods behind his home near British Columbia’s Wells Gray Provincial Park, the famed lichenographer waxes poetic on how much we have yet to learn from lichens. Story and photographs by Louis Bockner.

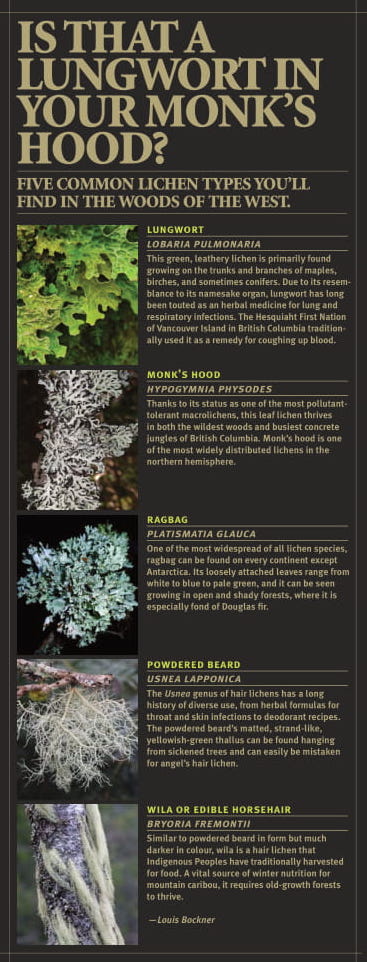

Amid the long shadows of an October afternoon, Trevor Goward stops beside a wheelbarrow-sized boulder; its surface is an abstract canvas of green, orange, and blueish-grey blotches, easily mistaken as stains to the untrained eye. But Goward is an expert of this particular natural wonder, especially here in the forest near his home on the border of Wells Gray Provincial Park in interior British Columbia’s upper Clearwater Valley. The circular swatches on the boulder are in fact a family of lichen called crustose, or crust lichen, and as Goward stoops his six-foot-five frame to examine them, he pulls a worn hand lens from the pocket of his well-loved black-and-red flannel jacket. Goward, who has penned several guides to lichens and is the namesake of the genus Gowardia, is renowned in the eccentric world of lichenology. He is the soft-spoken curator of lichenology at the University of British Columbia and a born naturalist in the tradition of Charles Darwin and Henry David Thoreau. Perhaps the most fascinating thing about him, however, is how four decades of self-taught, lichen-obsessed study have formed the 67-year-old’s world view, which bridges both spirituality and science. “It’s through the work of people like Trevor that we’ve really transformed our understanding of what it is to be a lichen,” says Goward’s long-time colleague Andy MacKinnon, the co-author of such seminal plant guides as Plants of Northern British Columbia, Plants of the Pacific Northwest Coast, and Edible and Medicinal Plants of Canada. “They’re organisms that can upend and upset some of our world view of how systems function,” he continues. “They are disrupters, and Trevor’s a bit of a rebel in lichenology.”

In biology, lichens have long been viewed as the archetypal example of symbiosis. They are a case “of multiple organisms living together in some sort of dynamic harmony,” Goward explains, as we stroll slowly through the forest behind his home, his eyes scanning for flashes of colour. They also present a conundrum that has puzzled and divided lichenologists for over a century. Until 1867, when a Swiss botanist named Simon Schwendener turned everything upside down, lichens were viewed as a singular organism, just like plants or fungi. The microscope-wielding Schwendener was the first to suggest that a lichen was actually a union between two organisms, a fungus and an alga or cyanobacteria, and although it took some time to catch on, Schwendener’s hypothesis was widely accepted as the norm by the beginning of the 20th century. But it wasn’t all unity and rainbows. Because the fungus quantitatively dominates the lichen body (or thallus as it is formally called), the assumption was, and often still is, that the alga was submissive, forced by the almighty fungus to photosynthesize from dusk until dawn to create sugars for its hungry host. “I think to this day, many lichenologists see the lichen relationship as being governed by the fungus,” says Goward, “but that’s a very two-dimensional way of looking at it. The way my essays look at it is that lichens are a system.”

Goward’s essays are a manifesto of sorts called Twelve Readings on the Lichen Thallus, which he published on his blog, Ways of Enlichenment. Written between 2007 and 2011, the essays provide a glimpse into Goward’s deeply philosophical views that both inspire and are inspired by his lifelong love affair with lichens. “Lichens, but especially macrolichens,” writes Goward in the essay “Reemergence,” “exist at a kind of conceptual doorway, a portal. When we look out this portal in one direction, through the microscope, what we see is multiplicity: the lichen as its parts, as fungus, as alga, as symbiosis, as ecosystem. But when we peer through the same portal in the other direction, at macroscale, what comes into focus now is unity: the lichen as emergent property, as physiologic entity, as organism.”

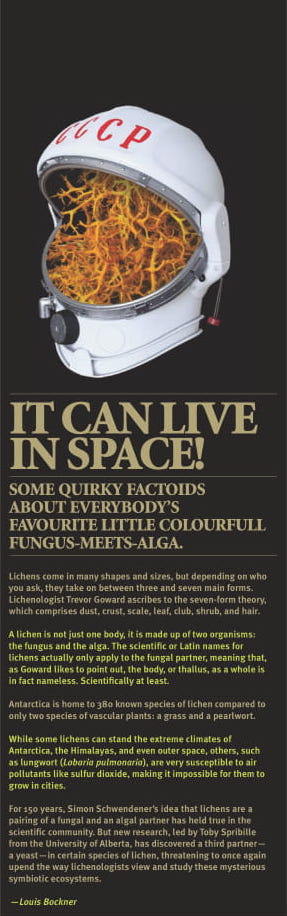

Much like mycology, the study of fungi, lichenology tends to attract eccentric naturalists who do not fit the classic image of a terse, lab coat-wearing scientist — a fact borne out by the common names of lichen, which often read like a fantastical science-fiction cookie recipe. Blistered navel, chocolate chip, fairy puke, moon glow, and witch’s hair lichen are just a few examples from the nearly 15,000 different lichen species on our planet. Types range from the flat-crust lichens that transform the surface of rocks to the trumpet-like pixie cups that create splashes of colour and are able to survive in the harshest of conditions. In a 2015 experiment, researchers at the Complutense University of Madrid sent two kinds of lichen — Rhizocarpon geographicum, or map lichen, and Xanthoria elegans, or elegant sunburst lichen — into space, where they were exposed to the environment for 15 days. Upon their return to Earth, all was well and they continued to thrive.

Goward first discovered these shape-shifting botanical mavericks while completing a seven-year undergraduate degree in Latin and French. In his early twenties, he began dedicating each calendar year to the study of a different facet of the natural world; having already knocked off astronomy, insects, birds, vascular plants, and mushrooms, he turned to lichens. It was a largely understudied field with few guidelines, a perfect fit for a passionate naturalist who recoiled at the academic hoop jumping that hard, reductionist science demands. Soon his backpack was filled with new species ready to be catalogued, scrutinized, and written about.

Thanks to the once-thriving BC Parks naturalist program, Goward got a seasonal job after university in Wells Gray Provincial Park, just two hours north of Kamloops, where he spent much of his childhood. This homecoming of sorts helped him realize the value of learning from a place over the course of a lifetime, much like Indigenous Peoples had done for generations before the arrival of colonialism. The park and its incredible diversity of lichens, plants, and wildlife became his muse, and by 1984, at the age of 30, he had bought a property adjacent to the park’s southern border. Thirty-seven years later, he still lives there with his partner, Curtis Björk, a botanist and fellow naturalist, and their friend Purple, a seven-year-old Australian Shepherd.

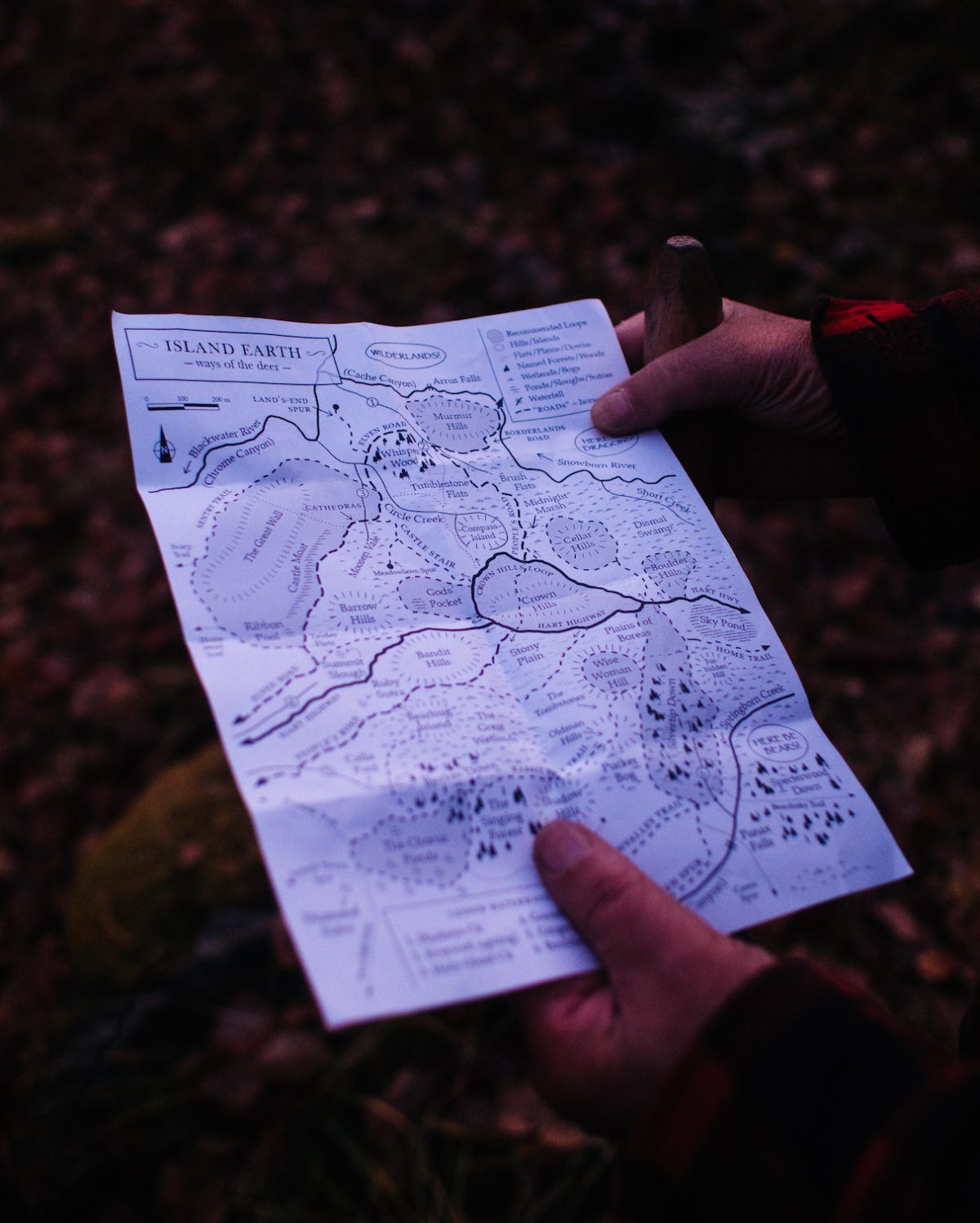

Goward’s rootedness in the land is apparent as he moves through the maze of deer trails he has mapped out and named in the forests near his home. His intimacy with the land comes from a deep, intellectual understanding garnered through a life of scientific learning and the specific wisdom that comes with observing an ecosystem season after season, year after year. It is this sense of place that Goward sees as the ecologist’s role in a future made increasingly uncertain due to climate change. “The naturalists will be the knowers of place,” he says, passing through a grove of cottonwood trees he has dubbed “Cathedras.” “They’ll be the knowledge keepers who spend an entire lifetime, a career you might call it, learning about the place they inhabit and learning its relationship to the planet as a whole.” He calls this keeper of knowledge the “naturalist of the middle way” in reference to uniting Enlightenment-era reductionist science with the holistic ecosystem- and relationship-based world view traditionally practiced by Indigenous Peoples across the globe. He calls this time of merging the “Enlivenment.” Currently he sees Western culture and its love of the “Enlightenment narrative” as being unsustainable and deeply damaging to the natural world. This belief, that human-caused climate change is eroding biodiversity, is backed up by the 2019 United Nations Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services report, which warns of a sixth mass extinction, an ongoing, human-caused phenomenon estimated to affect one million species, many over the coming decades. “We’re not doing it because we’re bad, we’re doing it because we’re embedded in a toxic story,” says Goward, “and if there is to be a future, what needs to change are the stories we tell ourselves, the stories we’re embedded in that define ourselves to one another and ourselves to the living world. Currently the dominating story is driving us to a place where we will, for generations to come, be impacted by the decisions being made today.”

This changing of narrative in Western culture, from human-centric indulgence and environmental ignorance to recognizing humanity’s role as stewards of the Earth, is being championed by teenage climate activists like Sweden’s Greta Thunberg and Autumn Pelletier, a member of the Wiikwemkoong First Nation in northern Ontario, who have both delivered speeches to the United Nations. But perhaps, given the Catholic Church’s traditional emphasis on relationships between human to human and human to God, the most telling sign of a shift from Enlightenment to Enlivenment can be found in Pope Francis’ 2015 encyclical letter on climate change titled Laudato Si: On Care for Our Common Home. In it he writes, “I urgently appeal . . . for a new dialogue about how we are shaping the future of our planet. We need a conversation which includes everyone, since the environmental challenge we are undergoing, and its human roots, concern and affect us all.”

So what is the best way to move from the antiquated, destructive narrative of the Enlightenment to the biodiversity-focused tale of Enlivenment? For Goward, the answer is found in the lichen thallus. “Lichens are sort of a key to both looking at the past . . . and looking to the kind of story we would need to enter if we ever hoped to give the world and our unborn children some sort of livable future,” he says, pointing out some thread-like angel hair lichen. “One of the things you learn that is true of all life on Earth is there is some sort of relationship between the parts to the whole and the whole to the parts. And that’s, of course, exactly what lichen is: a consortium of living organisms, unrelated, who are living as one.” By examining these relationships in lichen, Goward believes we, as human beings, might better understand our role in the larger ecosystem that is Earth’s biosphere. “We believe that we are entitled to certain things, but we forget that we also have responsibilities,” he says. “We focus on our rights and our individuality, but we don’t give much credence to our responsibilities to the greater whole.”

FOR THE PAST SEVEN YEARS, Goward has dedicated much of his time to raising awareness around the rapid decline of the mountain caribou, an animal that relies on hair lichens found in old-growth forests for sustenance in the winter months. He sees caribou as an archetype of Canadian wilderness, and while the provincial government and many scientists have taken the stance that the most immediate cause of their extinction is predation, Goward has maintained that habitat loss due to old-growth logging practices is the root cause of the issue. Now, with many of British Columbia’s herds either extinct or on life support and logging continuing apace, his hope for the species has dimmed, leading to a grim predicament he calls “the caribou prophecy.” “If we let the caribou die out,” Goward says, “then we are faced with the conundrum that the amount of caring it would have taken to save them is the same amount it would take to save our children or any other species.”

As he speaks, it is clear he that feels the window for saving the caribou has closed, a fact he is slowly coming to terms with. The silver lining is that he will have time to open a new chapter, one that involves the passing of knowledge from mentor to mentee. Over the past decade, he has been slowly transforming his property, Edgewood Blue, into a learning campus, where naturalists of all fields can come to share knowledge between generations. Working with The Land Conservancy of British Columbia, a non-profit organization dedicated to protecting important ecological landscapes for plants and wildlife, he has acquired funding to pay the bursaries of young naturalists who would benefit from mentorship. In May 2019, they launched the Deertrails Naturalist Program, described as “an intergenerational, place-based learning opportunity designed to facilitate the transfer of naturalist knowledge, both scientific and traditional.” Over the course of a week, 13 aspiring students gathered at Edgewood Blue to study with Goward, as well as fellow naturalist Briony Penn and ecologist Lyn Baldwin. There were also cameo instructions on volcanology by Catherine Hickson and mycology by MacKinnon. “I see Edgewood as being a place from which you go out into the wild rather than bring the wild inside,” Goward explains, going on to say that reading about the natural world is akin to reading a bike manual and thinking you can ride a bike. “They’re different experiences, and I’m not into teaching people how you theoretically might ride that bike,” he continues. “I’m into helping people get on that bike and ride into wild places where they can create a different relationship with nature than most people have these days.”

Standing beside Purple in the twilight of another passing day, on the land they both know so well, Goward is clearly embedded in this place. He is more at home than in his house, where the number of books rivals the thousands of lichen specimens he has carefully named and filed in little white envelopes. “Every now and then I find lichens looking back at me, and because they’re midway between an ecosystem and an organism, they lead us out of ourselves and into different ways of seeing and believing,” he says. Pausing, he takes one last look at the fading orange of the western sky before adding one last thought. “All this to say that the time of the naturalist, as ambassador to the wild, has come.”

Since writing this article, Louis Bockner has purchased a small hand magnifying lens and can be found crawling around the forests that surround his home in Argenta, British Columbia, examining the magical and mind-bending microscopic worlds of lichens.

Louis Bockner

Louis Bockner was born, raised and still lives in Argenta, British Columbia, where the toes of Mount Willet dip into the cold, clear waters of Kootenay Lake. He is a photographer and writer who loves delicious food and quirky characters.

Related Stories

Why You Tour Contest

This has nothing to do with our magazine, other than the fact that we're big fans of CMH (Hans Gmoser is a Kootenay…

Shredding Fairy Meadows

In this latest ski vid by Danny Leblanc, featuring Dave Crerar and Tom Harding, it's obvious Fairy Meadows is…

Why Japan Skiing is Awesome

For the past two seasons, Washington student and videographer Mattias Evangelista has skied the slopes and documented…

Why Locals Ski Naked in Golden, BC

Every summer, indecently exposed to the sun’s sizzle and with winter’s last vestige all but shrivelled up, boarders…

Why Do You Ski (or surf…or ride…or kayak…or…)?

An interesting little film here..the trailer for Lifted was released this past weekend at the Leavenworth Film…

Why Kootenai Fungi is The Shiitake

The Kootenai Fungi business in Kimberley, British Columbia, may have an unorthodox farming style, but its crops are the…