Coast Mountain Culture writer Vince Hempsall burns rubber at one of the Pacific Northwest’s oldest and toughest raceways — following in the tread marks of his grandfather’s checkered past.

Despite the assault of sound, I can appreciate the beauty of this place. Two concentric circles of perfectly smooth asphalt fan out from a rectangular core filled with colourful vehicles including a lime green stock car, a neon blue jalopy and a red and white ambulance. The lush rainforest encroaching on the south fence is a perfect foil to the empty blue and white grandstand. Bon Jovi on the stadium speakers and the incessant crescendos of six-cylinder engines are a reminder of why I made the pilgrimage to the land of the Flying Plumber.

The last time I was in the grandstand at Western Speedway in Victoria, British Columbia, I was a fetus. My grandfather, David Cooper, nicknamed the Flying Plumber, was participating in one of the final races of his long, storied career and my mother (who also raced cars during her teens) was there cheering him on with me in her belly. He retired from racing two years later, in 1974, and I was always disappointed to have never seen him in action. Because he was good. Damn good. For forty years he raced in his hometown of Victoria and throughout the Pacific Northwest winning stock car and sprint car races. He was the track champion at Western five years in a row. He’s been inducted into two halls of fame. He’s hobnobbed with the likes of Mario Andretti. And one Victoria fan, David Cooper McGuire, is even named after him.

Grandpa is 96 years old now and still driving but his arthritis keeps him from sliding in and out of the confined seats of race cars. So I came here without him to experience for myself a sport that I have very little appreciation for because:

- I was raised in rural Manitoba, away from any racing scene and

- I drive a Honda Element.

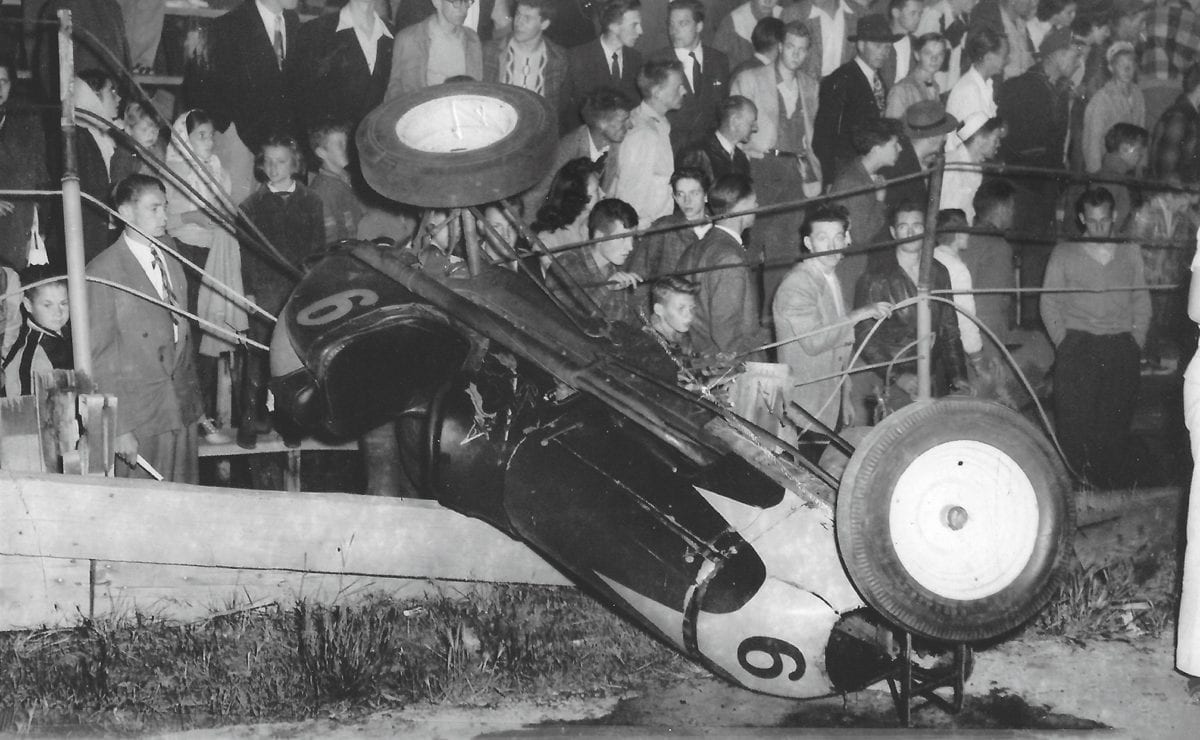

Opened in 1954, Western Speedway is Canada’s oldest racetrack still in operation. My grandfather installed the plumbing in the grandstand facility and remembers that much of the wood in its construction was salvaged from war-time houses. “I tell ya, I would finish a race in those early days and expect to see everyone on the ground,” he says, laughing. Instead, he and his fellow racers would occasionally find themselves on the ground after crashing and being thrown from their cars.

It’s crazy to me that Grandpa has survived as long as he has. In the early days he was reaching speeds of 140 kilometres per hour in open cockpit cars without roll bars. He tells tales of careening over fences and into trees, flipping upside down and breaking bones and various hospital visits including one in which he was suffering burns on his leg from a broken radiator. “That was a catholic hospital,” he remembers. “This nun came and asked what was the matter and I said my leg’s hurting but these guys only care if my neck is broken.’ So she came back with a whole bunch of gooey stuff and slapped it all on and wrapped it up. Jeez, I almost became a Catholic that day.” Incidentally, that story ends with him leaving the hospital and almost crashing into a gas station after his buddy fell asleep at the wheel.

He goes on to say that Western Speedway was the perfect place for him to hone his skills because the track is one of the hardest in the Pacific Northwest. Manager Daryl Crocker concurs. “The characteristics of our track are unlike any other in North America,” he says. “Other tracks have banked corners but ours are completely flat, yet they’re still tight and we have fast straightaway speeds. That’s why when our drivers venture out to other places, they’re usually quite successful, which is a reason our racing community is so strong here.”

Indeed, the scene in Victoria is very healthy given that the average attendance at Western Speedway on any given weekend evening is 2,000 people. A large part of this popularity has do with family ties, says Crocker. “It was so popular in the early days and bred so many racers that now we have a generational thing. When you’re born into it, it just becomes a part of you. There are tons of families who do this.”

All except mine. After my mother gave up racing to pursue a job as a flight attendant, no other relative followed my grandfather onto the track. This sport meant everything to him. And he means everything to me, which is why I don a fireproof jumpsuit and crawl into a stock car that once ran in the Daytona 500. The thing is literally held together by duct tape and zip ties but unlike most race cars, it has a passenger seat where I sit to enjoy the ride around the big oval at Western while local driver Gary Smith does all the hard work. And it is hard work! Before now I didn’t even know why car racing was deemed a sport. But Smith’s reflexes are so fast I can’t see his right hand lever the gearshift. The car vibrates at a rate that has my teeth chattering yet his gaze is steady as he accelerates to 170 kilometres per hour on the straightaways and avoids the walls by about 25 centimetres. I’m terrified.

When we finally pull into the pits I thank Smith and rejoin my wife who’s waiting for me in the grandstand. I tell her the experience was exhilarating but in my mind I think there’s no way I could do ever do that and be in the driver’s seat. Part of me feels bad, like I’ve failed our family’s legacy somehow. But perhaps this story will allow it to live on just a little bit longer.

Vince Hempsall lives in Nelson, British Columbia. A month after his experience on the racetrack he learned his wife was expecting their first child. He plans to take the family to Western Speedway as soon as the baby can walk.

Vince Hempsall

Vince Hempsall lives in the beautiful mountain town of Nelson, British Columbia, where he spends his time rock climbing, backcountry skiing and mountain biking (when not working). He is the editor of Kootenay Mountain Culture Magazine and online editor for the Mountain Culture Group.

Related Stories

Kaslo’s Flying Car Salesman

Got the nerve to fly a mini-car 180 clicks an hour? If so, make the trip to the historic town of Kaslo, British…

New BC Bike Race Movie Lands Today

BC Bike Race has released its third feature film, "The Journey," documenting the 2017 event. Watch it below. Director,…

Montana’s Barstool Race Turns 40

It's time to get stooled! Montana’s Barstool Race Celebrates 40 Years of downhill drinking. By Clare Menzel It began…

Singletrack 6 Race To Visit West Kootenays for the First Time

Singletrack 6, a mountain bike event that runs over six days in various communities in Western Canada, is coming to…

Cedar Shaker Cyclocross Race Returns to Revelstoke Oct. 21

The Cedar Shaker Cyclocross race at Revelstoke Mountain Resort returns for its fifth year on October 21, 2018.…

Rossland Bobsleds Race This Weekend – With New Rules

The Rossland Winter Carnival, which first began in 1898, happens this weekend and will include the ever popular Sonny…