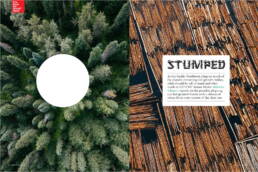

From Mushrooms to Huckleberries, the rampant, unmonitored harvesting of non-timber forest products for commercial purposes is a new challenge facing lawmakers. By Dave Quinn.

“Huckleberries are basically religion around here,” says well-known Cranbrook forester Jeff Allen. This sentiment neatly sums up a Kootenay reality: many locals plan entire summer and autumn activities around huckleberry picking, setting aside freezers full of the tart, sweet purple-black berries for winter smoothies, pies, pancakes and jams. That right to access local berries seemed inalienable, at least until last summer, when it was discovered that a commercial huckleberry harvest crew was in the Yahk region, south of Cranbrook, harvesting and sending hundreds of pounds of the prized wild fruit across the border to US buyers daily. It was the first time this activity had been documented in the region, and it set an ominous stage for yet another land-use conflict.

Michael Keefer is the Kootenay’s foremost expert on non-timber forest products (NTFPs), and he’s worked for over two decades with local native plants. In that time, he’s concluded that the harvest of wild NTFPs should, at the very least, be regulated, and for some highly valued products, like huckleberries, it should be banned outright. “I was very sad to see that activity had come to BC,” he says of the commercial harvest last year. “Heavy picking takes no account of wildlife or recreational or indigenous pickers.”

An NTFP is defined as anything that’s harvested from a forest except wood for lumber; items such as wild mushrooms, tipi poles, decorative plant materials and wild berries. When Keefer first began his job, there wasn’t any NTFP harvest data available in the province, so he and his colleague Tom Hobby undertook their own survey of wild harvesters, trying to determine how much product was being removed and what it meant to the people doing the removal. The results were intriguing. “The morel pickers were pretty much unanimously against regulation, but berry pickers had a higher level of agreement that there should be some sort of regulation on their activities,” Keefer says. “Morels are not really eaten by wildlife in any appreciable amount, as they tend to be really transient in the landscape. They show up for a few years after a fire, then they are gone, whereas huckleberries and other wild berries tend to represent a long-term, dependable food source, critical to grouse, bears, and many carnivores. Huckleberries are sacred to many people as well.” Those people, such as the Ktunaxa Nation, have constitutional rights to non-timber resources.

First Nations have relied on local berry patches for thousands of years, a cultural right theoretically guaranteed through the treaty process, and as of press time, the Ktunaxa were still formalizing an official response to this latest case of commercial interests raiding their cupboard. The provincial government’s stance on the issue is reminiscent of having a fox guard a henhouse. According to Jeremy Uppenborn, a senior public affairs officer with British Columbia’s Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development, “There are no current regulations specifically restricting commercial harvesting of huckleberries.” However, he recommends commercial harvesters remain aware of the impact that overharvesting could have on local wildlife populations, as well as general environmental, wildlife, land, and forestry legislation to avoid being faced with fines or legal action.

A commercial huckleberry harvest crew was discovered south of Cranbrook, harvesting and sending hundreds of pounds of the prized wild fruit across the border to US buyers daily.

“If we want to commercialize huckleberries let’s do it, but let’s do it in our farms,” says Keefer. “A team in Idaho was one step away from commercial viability of a cultivated huckleberry bush before they lost funding. There could have been mass releases of these plants that would have done well on our marginal farmland and acidic soils.” Another consideration for huckleberry harvesting is forest management. Productive huckleberry crops often take eight to ten years to establish after a fire and can last for many decades if left alone. Planting high-density conifers across a clearcut landscape minimizes this potential.

Following up on official complaints, natural resource officers inspected the commercial pickers’ campground. They observed no contraventions of the Land Act or the Forest and Range Practices Act; however, a dangerous wildlife protection order was issued by a conservation officer under the Wildlife Act, as a result of large quantities of culled berries left to rot in and around camp, and the presence of a young grizzly bear near camp. Essentially, the province’s message to pickers in the first conflict around British Columbia’s commercial huckleberry harvest was to clean up their camp. That said, this is likely only the opening act in a clash that could pit commercial harvesters against local sustenance pickers, wildlife advocates, and treaty-backed First Nations.

Dave Quinn

Born in Cranbrook, British Columbia, Dave is a wildlife biologist, educator, wilderness guide, writer and photographer whose work is driven by his passion for wilderness and wild spaces. His work with endangered mountain caribou and badgers, threatened fisher and grizzly, as well as lynx and other species has helped shape his understanding of the Kootenay backcountry and its wildlife, and help shape his efforts to protect what remains. His writing and photography has helped fill the pages of publications such as British Columbia Magazine, Westworld, the Financial Post, Backcountry, Adventure Kayak, as well as the Patagonia and MEC catalogs.

Related Stories

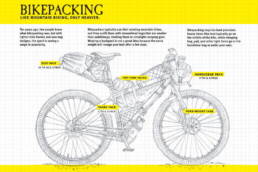

Bikepacking Versus Bike Touring – What’s The Difference?

In the recent issue of Kootenay Mountain Culture magazine we feature a story about writer Andrew Finley's experience…

BC’s Old Growth – What Should Be Cut and What Should Be Left? Various Voices Weigh In.

As the Pacific Northwest clings to much of the planet’s remaining old-growth timber, what should be left to stand and…