If a foreign army invaded Vancouver or Seattle, would you help defend your country? Ukrainians faced that choice when Russian troops attacked in early 2022. Ukrainian professional athletes and guides who joined the civilian defence force have found their skills invaluable on a battlefront far from the summits and slopes they used to visit regularly. We reach out to skiers, bikers, climbers, and other mountain recreationalists to learn how their lives have been impacted by war. By Tyler Austin Bradley

“The big day has come. Severodonetsk, the front. It is my turn to rest on duty in the trenches, and I, as unit commander, gather with our boys before going to ground zero. Suddenly, a dense mortar shelling begins. Everyone manages to hide in a hole, but it goes on for a long time. Then someone screams. Pasha. I see a hole through his chest. Fuck, that’s a pneumothorax. I cover the hole with my palm and another soldier assists. I will never forget that feeling of bloody bubbles forming around my hand.”

WHEN HE WROTE the above, 36-year-old Andrey Nenko was helping defend Ukraine against the Russian invasion. He shared his story with me in between tours on the battle lines, a world removed from the mountain slopes he was accustomed to. As an owner-operator at Golden Ride in the Ukraine Carpathians, Nenko works as a guide, cat driver, avalanche safety coordinator, instructor, and first-aid attendant. It’s a lifestyle many Kootenay residents can relate to: he gets paid to ski tour in the winter and he mountain bikes in the summer. But when Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24, 2022, Nenko felt compelled to help defend his country. He left his job, said goodbye to his wife and daughter, joined the army, and travelled 1,000 kilometres (620 miles) west to the front.

He quickly found himself moving up through the ranks. “Avalanche risk management is not so different from risk management in war,” he says during one of our late-night phone conversations. “But in war, the danger is often all around.” As with forecasting and avalanche fieldwork, the habit of observing and recording becomes second nature amid hostilities. Nenko is also accustomed to rationing, multi-day traverses, and operating in challenging conditions with little sleep, so he’s better equipped than many in a freshly mobilized, civilian-heavy defence force.

Whether in a military capacity or in response to the unfolding humanitarian crisis, members of Ukraine’s mountain community have found their skills invaluable. Olenka Filipova, 42, is a celebrated climber, skier, and instructor who had to flee her home with her young son. “My outdoor skills did help me to cope with stress, assess the risks, and plan the course of action,” she says. “For example, I was able to pack the essentials for a long journey into the unknown very quickly. Knowing my equipment was also very reassuring and helped me to stay organized.” She eventually found sanctuary in Poland.

Manufacturers of outdoor gear and clothing were also pulled into the fray. People behind such local brands as Hard Ride and Newborn pivoted in the early days of the invasion and are now supplying the military with tactical webbing, packs, camouflaged clothing, and army boots. Vladimir Degtiarov, 43, owner of the retail store Pro Boardshop in the country’s capital city of Kyiv, says working in a war zone presents logistical challenges. “It is not easy when there are air-raid alerts in your city every day and you have to go down to the bomb shelter.” Like Nenko, Degtiarov misses the mountains. Underground shelters, subway tunnels, and basements are the antithesis of what his peacetime life looked like. “We constantly travelled to the mountains, organized music and sports festivals, competitions, and spring camps,” he says. “We have a lot of beautiful places that can only be reached by splitboard or ski touring. But for now, we live one day at a time and can’t plan anything for the future. We cannot hide from Russian missiles anywhere in Ukraine.”

THE 2022 INVASION OF Ukraine bookends a century of conflict and hardship for the country, the second largest in Eastern Europe after Russia. Its battle for independence began with the Ukrainian-Soviet War, which lasted from 1917 to 1921, and ended with Ukraine’s defeat at the hands of the Red Army. A decade later, an estimated three and a half to five million Ukrainians perished in the Holodomor, or Terror-Famine, which was caused partly by communist agricultural collectivization strategies and their fallout. Political strife continued through the 20th century until 1991, when the Soviet Union dissolved and Ukraine emerged as an independent state. But in 2013, Ukrainians rose up again during what are now known as the Euromaidan protests, a reaction to the refusal of then-president and Russian ally Viktor Yanukovych to sign an agreement that would have integrated the country more closely with the European Union. Yanukovych was ousted in early 2014, and weeks later, Russian President Vladimir Putin sent forces into the Crimean Peninsula, an important naval staging area on the Black Sea, and annexed it from Ukraine.

These instances of Russian political interference and state-sponsored violence are integral to modern Ukrainian identity politics and have spurred the country’s youth-driven renaissance, which looks westward and embraces such cultural symbols as punk rock, hip-hop, skateboarding, street art, cafés, and micro-brewing. The younger generation now stands shoulder to shoulder with traditionalists whose values neatly overlap theirs: freedom, independence, and self-governance.

Many of the people I interviewed for this story see their struggle as deeply existential. For example, mountain biker Kyrylo Sirenko, 29, remembers the conflict of 2014 well because it changed the trajectory of his life. “In 2014, right in the middle of a bike trip, I found out that I can’t go home anymore because Russia occupied Luhansk,” he says. He lived in a hostel room in Kyiv with 13 other people until he eventually secured his first bicycle-industry job wrenching in a shop. He firmly believes that bikes helped him survive that difficult time, as well as films, like the New World Disorder mountain-bike series, produced by Kootenay-based Freeride Entertainment, which encouraged him to carve out an existence where mountains are key. “Step by step, I came to the races, podiums, bicycle-events organization, trailbuilding, and working in the industry,” he says. “I fell in love with the mountains for the rest of my life.”

Fast forward to 2022 and Sirenko has had his life changed a second time. “I woke up at 5 a.m. because of the explosions,” he says. “My brother called me and said that Russia began a full-scale invasion.” He finds comfort in movement and continues to bike and train when he can, but his voice carries a note of lingering bitterness. “This year, I planned to organize a second season of [the] Ukrainian Enduro Series, a few downhill and pump-track races. I planned to restore a bike park, buy a new bike for this season, and spend my vacation riding in a few other European countries,” he says. “It’s all gone now.”

LIKE NENKO AND FILIPOVA, Sirenko hopes the global community recognizes not only the importance of Ukrainian sovereignty but also the similarities between them and mountain people around the world. Every Ukrainian climber, biker, skier, snowboarder, or guide who was contacted for this story emphasized the importance of recognizing how precious peace is, as well as the freedom of spending time in high places.

When his daughter Victoria was two months old, Nenko and his wife, Anna, took her on a trek through five countries, from Ukraine’s Carpathians to Romania, Serbia, North Macedonia, Albania, and Montenegro. It was a self-guided trip, and the young family wandered past 2,500-metre (8,200-foot) peaks, swam in mountain rivers, and slept in a tent most nights. “The people we met were surprised, to say the least,” Nenko recalls. “The Romanians nicknamed my daughter ‘Super Beba.’ We’ve been calling her that ever since.”

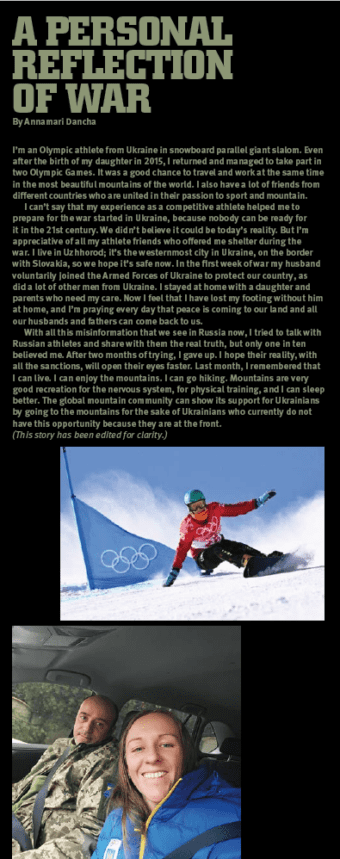

Ukrainian Olympic snowboarder Annamari Dancha, 32, also has a daughter. She takes care of her at home while her husband fights with the Armed Forces of Ukraine. Recently retired from the competitive circuit, Dancha was not content to just sit by while others fought, so she joined the battle in her own way by contacting Russian athletes directly to refute the claims made by state-owned media that Putin’s invasion is a special operation to rid Ukraine of so-called dangerous nationalists. It was an uphill battle. “Only one in ten believed me,” Dancha says. “After two months of trying, I gave up.” (For more about Dancha, see the sidebar above.)

When the subject of propaganda comes up with Nenko, his response is adamant. “The most important thing is publicity. All over the world there are millions of refugees, people that lived peaceful lives, had their dreams, their families, their businesses. The destruction of our homes, our culture, this should be talked about and addressed,” he insists. “It mustn’t be forgotten or forgiven.” It’s obvious war has changed Nenko. Still, he holds fast to the prospect of peace for his loved ones and better times ahead when they’ll be able to enjoy the mountains together again.

“There is nothing worse than realizing it is the end. I hold Pasha’s head, cover his eyelids with my hand, and pray over him. Pasha gets put in a carry bag. I put his camouflaged panama hat in too. For the past two days, I’ve noticed I stutter a little. From time to time, I cry when no one can see. No one has died in my arms like that. I know for sure that we didn’t have a chance, but we tried and did everything we could. Pasha has two children.”

Tyler Austin Bradley is a writer who lives in Hills, British Columbia. He looks forward to an eventual trans-Carpathian tour with his Ukrainian friends.

Tyler Austin Bradley

Tyler Austin Bradley lives in Rossland, British Columbia, earns his day-job paycheque in the neighbouring city of Trail and plays in the mountains as much as possible. He is currently adapting Ski Bum: The Musical for screen, busy at work on his art and is developing a children’s storybook about a flying squirrel.

Related Stories

RED Mountain Releases Athlete Video

A lot of people may not realize just how many pro athletes RED Mountain and Rossland have been cranking out over the…

Insane Mountain Beat Boxin’

We don't know who this guy is, or where he came from. He showed up at the Kootenay Coldsmoke PowderKeg Slopestyle last…

The Gathering at Red Mountain

This upcoming Easter weekend RED and POWDER Magazine are presenting the 2nd annual Gathering at RED. Come hang with…

The Gathering Returns to Red Mountain

Presented by Salomon, the Gathering at Red Mountain, an event of mountain photographers, filmmakers, and artists is…

Framed in Leavenworth With Coast Mountain Culture

This past weekend, CMC was on hand to sponsor and participate in Leavenworth's Framed Photographer Invitational, where…

Coast Mountain Culture Launches Premiere Issue

You may have seen a copy of the new Coast Mountain Culture Magazine (CMC) floating through outdoor veins throughout…