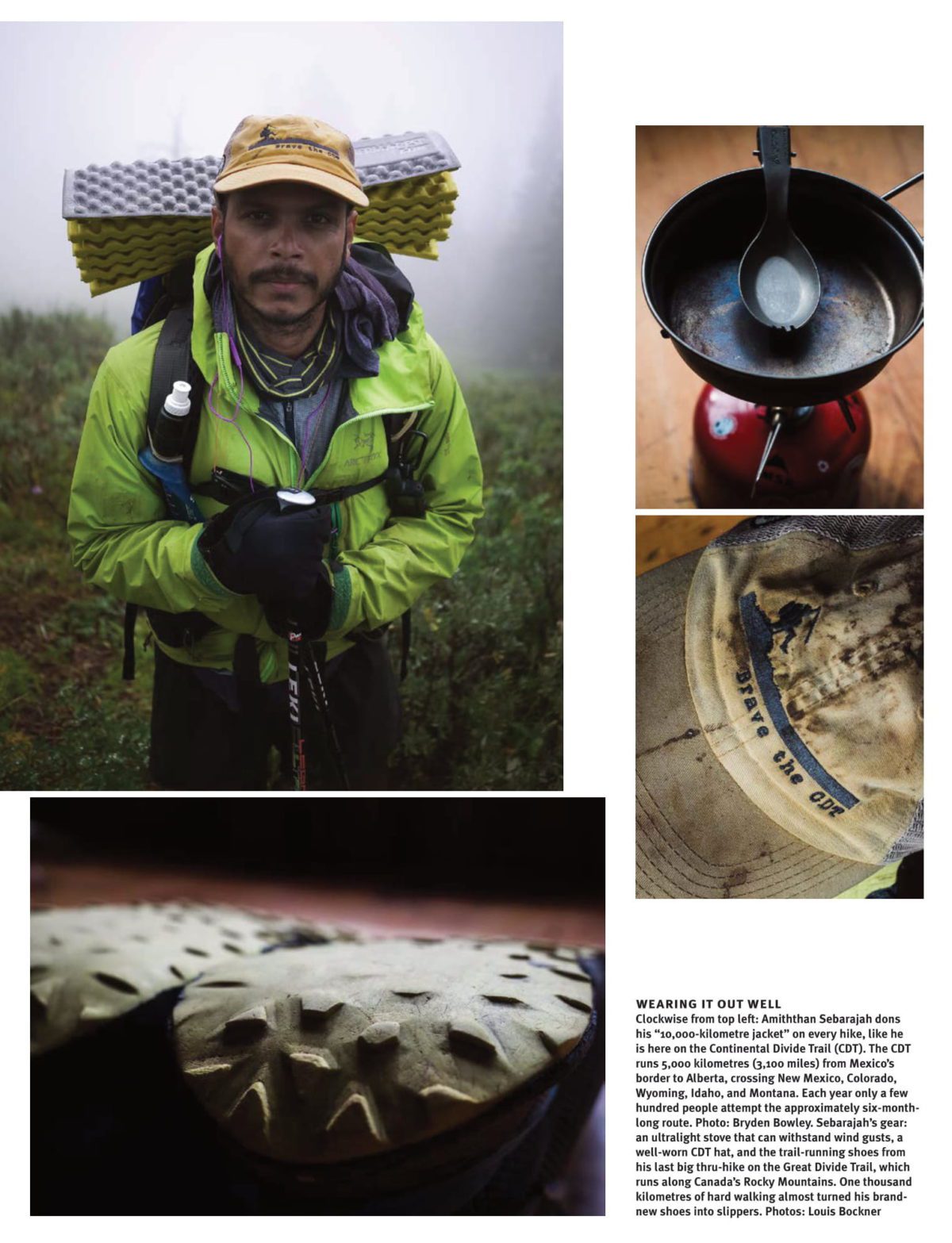

Amiththan Sebarajah was a child when he immigrated to Canada from Sri Lanka to escape his birth country’s violent civil war. Now a Kootenay resident and accomplished thru-hiker, the 38-year-old tackles the duality of challenging long-distance solo routes and the lingering trauma of redefining home. Words and photos by Louis Bockner.

DEEP IN THE CANADIAN wilderness, a man walks. He moves quickly along a faint trail, powerful legs propelling him onward, step by step, through the rugged, humbling expanse. His name is Amiththan Sebarajah and he’s in the middle of a 1,130-kilometre hike, shadowing the spine of the Rocky Mountains. It’s a formidable journey. Forty-kilometre days are common, and by the third week his body begins to eat itself. Yet somehow, out in the wildness, there is healing in the hardship. And compared to other journeys he has taken, this one isn’t so bad.

IT IS JUNE 22, 1995, and a young Sebarajah, wearing an oversized orange puffy jacket, steps out the doorway of a commercial airliner. Despite the warmth of a new Toronto summer he is cold. He has come from Batticaloa, a town in the eastern province of Sri Lanka, an island country off the southeast coast of India entrenched in a civil war since 1983. Until now, he has only known ubiquitous, chaotic violence and repression. And all he knows about this new home of unimaginable strangeness is that apples grow and snow falls. One foot in front of the other, he descends the stairs to the tarmac.

Almost three decades later, Sebarajah, now 38, lives in the small community of Meadow Creek, British Columbia, at the north end of Kootenay Lake. The natural beauty and quiet lifestyle drew him here in 2013, and after visiting on and off, he and his partner, Valerie, finally moved to the region in the spring of 2020.

He is stocky and strong; a patchy black beard matches his cinder eyes. As a thru-hiker — someone who hikes an established long-distance route with continuous footsteps in one direction — he has clocked over 10,000 kilometres on trails across the world, including the Appalachian and Arizona Trails in the United States, the Great Divide Trail in Canada, and the Te Araroa in New Zealand. Yet when he walks, he carries with him more than meets the eye. Somewhere between the ultralight tent and quick-cook rice is a history of hard journeys with life-shattering transitions, and there, nested beside the thin sleeping pad, is a mind simmering with deep contemplations on the state of the outdoor community he has, against many odds, become a part of.

The utter displacement that occurs when a refugee undertakes a journey like Sebarajah’s leaves little to hold onto. “It’s a total epistemological shift, where everything that you conceived of how your life would be changes fundamentally,” he says between mouthfuls of curry, which he is eating with a collapsible spoon from a lightweight, sealable metal container while sitting on a friend’s porch. “It’s a reformation of ideas about how much place becomes part of your identity and how that can become fractured, splintered, and dislocated.”

But pieces do remain. There is the lingering aroma of spiced food, or the hint of an accent when he speaks in his thoughtful, decisive, and articulate way. And there are the memories of war that resurface when only heartbreaking beauty and inescapable silence accompany him on the trail. “The war is always there; that dislocation is always there,” he says. “I’m always reminded of it by how much I can feel at home in a little tent, something that will forever be superimposed on having not felt a true sense of home in a very long time.”

When he was eight, his father fled Sri Lanka illegally, eventually seeking asylum in Canada. While the details of that journey are unknown to Sebarajah, the reason behind his father’s decision to leave is clear: if he hadn’t, he would have been assassinated. Three of Sebarajah’s uncles were murdered by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) — one of the separatist guerilla groups at war with the Sri Lankan government. One of his uncles, a school principal, was tortured for several days before being killed. His body was hung from a lamppost to convey a message: dissent against the cause is unacceptable, even if you are Tamil, like Sebarajah’s family. He, along with his mother and two sisters, wouldn’t reunite with his father for four years.

This fight for nationhood left him aware that land holds power, and it’s something he thinks about often on the trail. While hiking the Great Divide Trail through the Rockies, he came across a boulder covered in petroglyphs painted millennia ago. The visceral knowledge that Indigenous Peoples had been treading that land and calling it home for so long brought a sense of perspective to many issues he sees plaguing the outdoor community. “I think we have to really think about our relationship to the land,” he says. “The land does not belong to you; you belong to the land, and anyone who tries to tell you otherwise is trying to impose an arbitrary, antiquated, colonial system. No one should be able to tell you that you can’t be somewhere from that context.”

Yet the world doesn’t always see it that way, and old systems cling. While hiking the Appalachian Trail — a 3,500-kilometre thru-hike that runs from Georgia to Maine in the eastern United States — a female hiker he met on the way didn’t make it to the meeting point they’d agreed upon. Fearing the worst, he flagged down a passing police car to get help. He was immediately detained in a jail cell, his skin colour making him a prime suspect. It wasn’t until she called his cell phone that they released him.

So, despite a desire to tell people of all races that they belong outside, Sebarajah often doesn’t know what to say to fellow people of colour who ask him how they can stay safe while thru-hiking or discovering the outdoors. “If it’s going to happen, if the machinery of white supremacy is going to turn against you and you become the target,” he says, “there is nothing that you are going to do that will save you.”

This weight, unlike the carefully measured gear he packs for a thru-hike, is unquantifiable. It’s the constant requirement of situational awareness that Black writer and hiker Latria Graham wrote about in a 2020 article for Outside magazine titled “Out There, Nobody Can Hear You Scream.” “I want to tell you to make sure you know what it means not to need, to be so prepared that you never have to ask for a shred, scrap, or ribbon of compassion from anybody,” she writes. “But that is misanthropic — maybe, at its core, inhumane.”

When asked why he continues to go into frontier spaces, despite the threat of violence and uncertainty, Sebarajah is quick to answer. “Because I’m a human being on this planet and I have every right to be there, just like everyone else. It’s as simple as that.”

FOLLOWING HIGH SCHOOL, Sebarajah received a full-ride scholarship to study engineering at the University of Toronto. He began attending meetings put on by other Tamil students that focused on raising awareness about the struggle of Tamils in the civil war. At the time, the greater Toronto area had the largest population of Sri Lankan Tamils outside of Sri Lanka. Sebarajah was impressed by the people he met and soon became a founding member of the Tamil Student Volunteer Program, which grew rapidly, chapter by chapter, across Canada, the United States, and England.

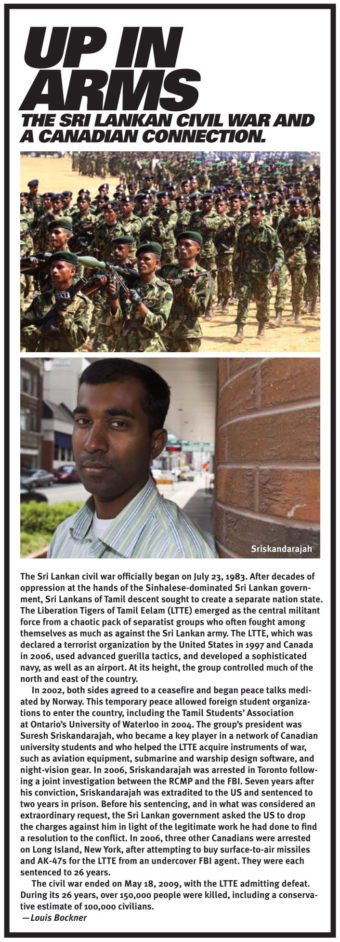

In 2002, when Norway intervened in Sri Lanka to hold peace talks, he helped organize a trip to Sri Lanka to deliver used computers and other aid to LTTE-controlled regions — his first and only time returning to his country of birth. As he lifted .50 calibre shell casings from the sand of old battlefields and met leaders of student movements and the LTTE, the war became real all over again. It was also a pivotal moment for the LTTE’s relationship with Canada. The organization saw an opportunity to create influence abroad in the impressionable young minds of these students. Ultimately, this relationship would lead to the arrest of four young Tamil Canadians (see sidebar).

Shortly after returning home, Sebarajah left the volunteer program and decided to transfer to Toronto’s York University, where he completed a master’s degree in English with majors in discourse analysis and cultural studies. It was between this graduation and the beginning of a PhD program that he discovered the Appalachian Trail and the world of thru-hiking. His life was blown off course and onto the trail.

While researching the hike, he was unsure whether he could spend one night alone in the wilderness, let alone 30. Having lived in Toronto since arriving from Sri Lanka, he came up against what he calls the green ceiling, a barrier to the outdoor world that seems almost impossible to overcome, especially for people of colour. “It’s the gear, the cost, the knowledge, plus the logistics of getting out of the city,” he says. In addition, he didn’t see himself in any of the stories that were represented in the outdoor industry, and despite working as a gear tester for companies like Icebreaker and Arc’teryx, he still doesn’t always feel at home. “The first time I saw the Icebreaker Touch Lab store in Vancouver I felt this huge inferiority complex, this body feeling of ‘that place doesn’t belong to me,’” he says. “Even if I do see myself represented in that space, I’m constantly reminded that I’m an anomaly, which reinforces the idea that you’re an outsider.”

Now, 10,000 kilometres later, he is a vocal advocate of inclusivity and diversity in the outdoor community and recently helped found a non-profit organization, Unfilter, dedicated to helping new thru-hikers overcome these barriers by offering gear, mentorship, and financial support. While he admits there is no formulaic answer to the issue of inclusivity, he does believe that challenging, disruptive conversations need to happen. “I think the work has to be done on all fronts and people like me need to say, ‘Yes, what I do is different, but at the same time there’s all these other things that I do that are more or less the same and those are just as worthy of representation.’” To make his point he pauses and adds, “Ask me about what I eat on the trail, not what I eat on the trail as a coloured person. That’s a very different question.” The answer, in case you were wondering, is often rice and curry.

“The land does not belong to you; you belong to the land, and anyone who tries to tell you otherwise is trying to impose an arbitrary, antiquated, colonial system.”

IN THE OPENING PARAGRAPH of an article Sebarajah wrote for the CBC about his experience hiking the Arizona Trail, he mentions a man named Earl Shaffer. Shaffer was a World War II veteran who hiked the Appalachian Trail in 1948 to “walk the army out of my system.” For Sebarajah, this idea of using thru-hiking as a means of reconciling a painful past and unsettling present rings true.

According to Sebarajah, everything you do on a thru-hike is determined by two decisions: where you’re going to eat and where you’re going to sleep. Everything else hinges on these two factors, which leaves plenty of time to think. “When you’re alone for 23 days, your body is being deprived of nutrients and you’re constantly being bombarded by this magnificent sublime and the relentless silence; you realize that there’s just you and the parts of yourself you may have hidden or run away from. You realize that the idea of something being inhuman is an oxymoron because everything we do, every act of kindness and every atrocity, is human.”

Seeing the world through this lens has offered a certain sense of understanding for the violence he has experienced and the oppression he continues to witness. They are symptoms of humanity caught in the chaos of itself, a revelation encountered when there is enough space to see the Anthropocene from a distance. For Sebarajah, it’s hard to imagine a better place to gain that perspective than within the vastness of wilderness. “People do all sorts of meditation, and personally, for me, that’s all it is,” he says. “You match your footsteps to your breath, and you meditate as you walk and walk and walk.” On the trail, kilometres pass and time fades. Memories and thoughts ebb and flow as exhalations follow inhalations and heartbeats follow footfalls.

Louis Bockner

Louis Bockner was born, raised and still lives in Argenta, British Columbia, where the toes of Mount Willet dip into the cold, clear waters of Kootenay Lake. He is a photographer and writer who loves delicious food and quirky characters.

Related Stories

Summer 05 – The Evolution of the Revolution

Seasons, weather . . . life. Cycles are fascinating things. Spinning on a never-ending journey, always coming back on…

Summer 06 – The Four Points of Adventure

For centuries human beings have broken complex realities and concepts into groupings of four called quaternities.…

Winter 06/07 – The World of Mountain Culture

While each continent has its highest peak, it also holds the people who live under those peaks. Those who look up to…

Backyard Booty Cometh…Again

It was another glorious evening of multimedia marvelousness. The 6th Annual Backyard Booty at Nelson's Capitol Theatre.…

Powder Highway Ultimate Ski Bum Contest

We had to post this simply because it features KMC Editor, Mitchell Scott, in his formal acting debut. The contest is…

The Gathering at Red Mountain

This upcoming Easter weekend RED and POWDER Magazine are presenting the 2nd annual Gathering at RED. Come hang with…