The tiny town ski hill: Open four days a week. One T-bar or a rope tow. Night skiing. A lodge so retro you should be wearing jeans. For many communities off the beaten path, they are a lifeline to family winter fun. But tight margins, rising insurance costs, and aging equipment make it challenging for hills to stay afloat. With a global pandemic impacting international travel, however, struggling community ski hubs may be the next destination hot spots. By Matthew Tufts

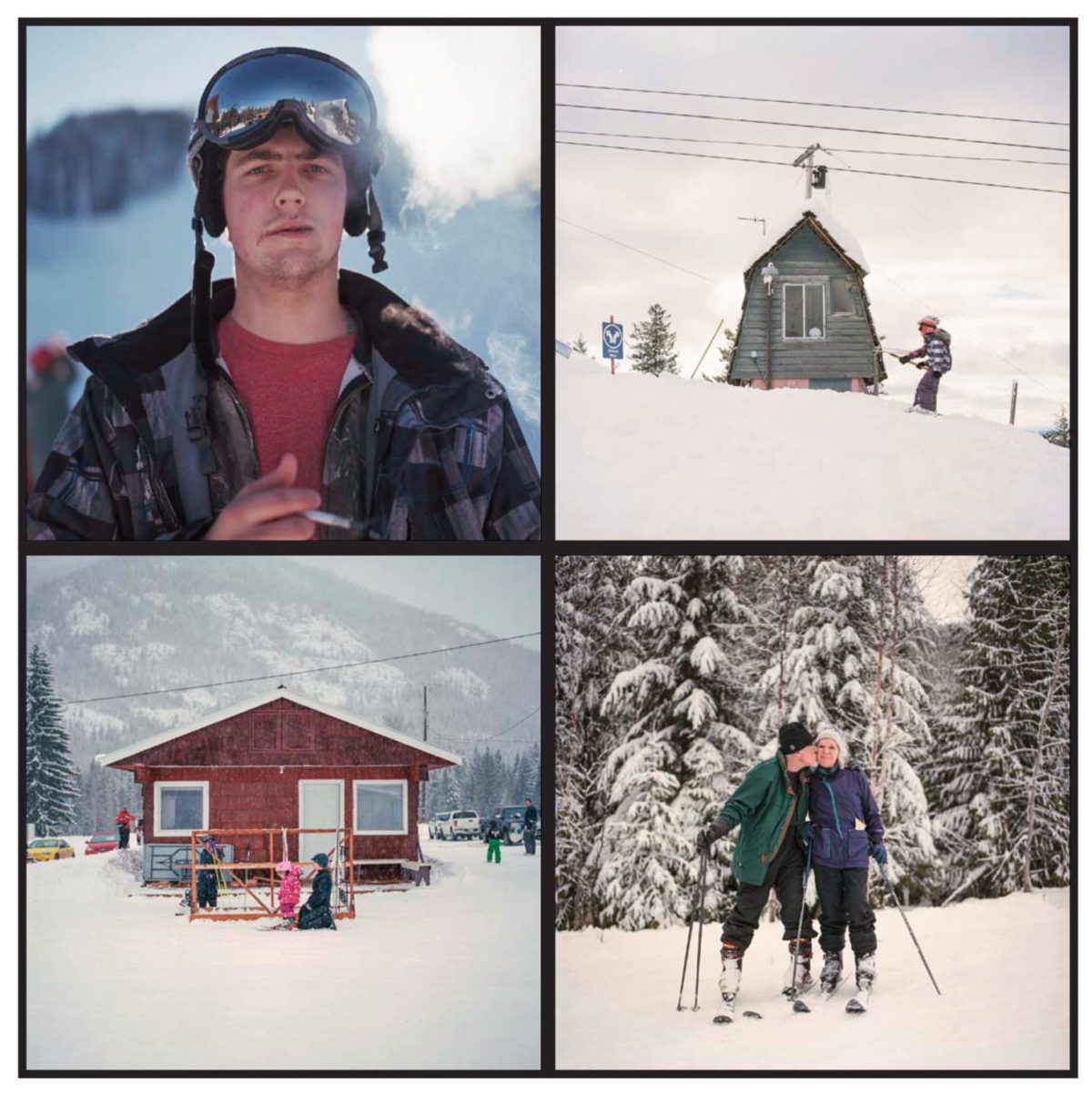

it’s 6 p.m. on a Friday in February, and three men gather within the incandescent lighting and cedar aroma of Butch Warantz’s woodworking shop, deep in discussion regarding a most pressing matter: an overabundance of hot dogs. Talk of superfluous sausages and the looming youth ski race soon fades, and the conversation shifts to a groomer in need of repair, T-bar gremlins, and early rumours of the locally coined “Kelowna virus.” One could assume the Old Milwaukee can on the table signals the end of the work week, but the work is just beginning for Summit Lake Ski and Snowboard Area volunteer directors Warantz, Rob Stevens and Vice President Mike Webster, as it is with numerous small ski-hill operators around the Kootenays in British Columbia.

Summit Lake is 19 kilometres southeast of Nakusp and 27 kilometres north of New Denver on the edge of the Slocan Valley, the west side of British Columbia’s famous Powder Highway. Since 1961, a simple T-bar and rope tow have provided access to the hill’s modest 150 metres of vertical relief on 12 hectares of skiable terrain. Surreptitiously located in the geographic heart of skiing’s most coveted cold-smoke haven, the community hill joins the ranks of the Salmo Ski Hill, the Wapiti Ski Club near Elkford, and the Phoenix Ski Area between Greenwood and Grand Forks, to round out an array of family-friendly feeder hills in the Kootenays. These operations provide a community service for rural, working-class locales with simple but efficient means: surface lifts, small cafeterias, and day-use “lodges” that better resemble warming huts.

While appearing like pared-down versions of their full-scale resort neighbours, these rural hills all offer an amenity not so commonly afforded by industry heavyweights: night skiing. But Summit Lake’s night moves are less a nostalgic novelty and more a service emblematic of what the small ski hill and its peers stand for: accessible entry to a sport that increasingly plays to a more exclusive crowd. After-dark turns cater to local children and families that can’t get away from the standard work week and school, and its $16 price tag for Friday evenings keeps that door open to the masses. As Summit Lake supports skiing in its community, the community reciprocates support for its local hill.

During my visit, I enjoy a handful of dimly lit T-bar laps before meeting a family from Revelstoke, British Columbia, at the top of the hill. They drove two hours south after work, skied, rented an Airbnb in Nakusp, and took the family out to the nearby hot springs — a complete ski-weekend vacation — all for less than the price of a single day pass at Whistler. There are no lineups, and the hill was better suited for the young family because of its beginner-friendly terrain. “Without kindergarten, it’s hard to progress,” another parent tells me. “It’s tough to just jump into first grade.” World-renowned destinations like Revelstoke Mountain Resort and Kicking Horse Mountain Resort in Golden, British Columbia, are lauded for many things, but beginner terrain and an introductory atmosphere aren’t among them. For parents, Summit Lake serves as both an escape from the crowds and a stepping stone for children.

Closer to home, the hill has had to adapt to frequent fluctuations in Nakusp’s population, following the economic decline of the timber industry in the region. “There are hills and valleys for every resource-based community, but we feel pretty good,” says Stevens, whose parents were deeply involved with the hill at its inception nearly 60 years ago. “In the past few years, there’s been a whole lot of young families moving out here.” While the population roller coaster of resource-driven rural towns can spell the end for team sports, the flexibility of individual and small-team competition has allowed skiing to survive the Kootenays’ boom-bust cycle. That’s particularly critical for small ski operations like Summit Lake, where youth ski instruction and competition are core tenets — and principal financial drivers.

“Our elite clientele is school kids and their families,” Warantz chuckles outside his garage workshop, 100 metres from the hill. He has been involved with the ski area since he moved to a house across the street from it several decades ago. “[The kids] get their lessons during the school program and then bring their families up skiing. So it’s gotta be affordable or we just won’t get anybody coming down to the hill.” This puts small ski operations like Summit Lake in a unique position for the upcoming 2021 season. As destination ski resorts around the world prepare procedural changes to deal with concerns around the COVID-19 pandemic, community operations stand to face a different array of challenges and, perhaps, benefits.

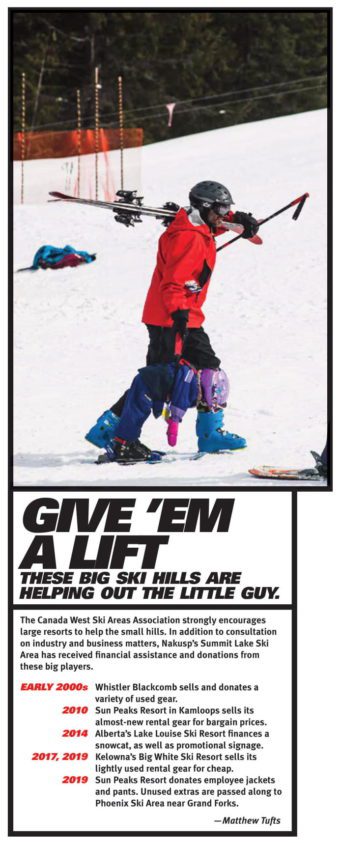

For subsidized, non-profit ski hills, the bottom line doesn’t carry as much weight on a year-to-year basis as it does for a large commercial operation seeking return on investment. Many rural hills never break even on their own between equipment upkeep, rental fleets, and necessary capital expenditures, even with strong volunteer action and generous support from large resorts (see the “Give ‘Em A Life” sidebar above); as a result, many are funded as public services. About 15 years ago, Summit Lake’s insurance policy climbed beyond their means, from several thousand dollars annually to nearly $20,000 today. Thankfully, the neighbouring communities passed a small tax via reverse referendum — approximately $2.50 per resident from New Denver to Fauquier to Nakusp — and the region saved its ski hill. “Without that we for sure would’ve had to fold because we just don’t generate quite enough money,” recalls Warantz. “The way it ends up, [the municipality] is pretty happy about the fact that we create jobs, and we don’t really put much money away. We’re a non-profit society.”

For subsidized, non-profit ski hills, the bottom line doesn’t carry as much weight on a year-to-year basis as it does for a large commercial operation seeking return on investment. Many rural hills never break even on their own between equipment upkeep, rental fleets, and necessary capital expenditures, even with strong volunteer action and generous support from large resorts (see the “Give ‘Em A Life” sidebar above); as a result, many are funded as public services. About 15 years ago, Summit Lake’s insurance policy climbed beyond their means, from several thousand dollars annually to nearly $20,000 today. Thankfully, the neighbouring communities passed a small tax via reverse referendum — approximately $2.50 per resident from New Denver to Fauquier to Nakusp — and the region saved its ski hill. “Without that we for sure would’ve had to fold because we just don’t generate quite enough money,” recalls Warantz. “The way it ends up, [the municipality] is pretty happy about the fact that we create jobs, and we don’t really put much money away. We’re a non-profit society.”

Moreover, hills of that size don’t rely on out-of-town visitors. Ahead of a season presumed to emphasize local travel, Summit Lake and its diminutive peers won’t have trouble filling accommodation — because they don’t have any. While the base lodge is small and may struggle to accommodate social-distancing protocols, being indoors is not integral to its operation. Local families show up. They ski. They drive home. There’s little to no emphasis on the auxiliary amenities proffered by full-scale resorts. And that simple assertion, at the end of the day, is what keeps locals coming back. “You can still get first tracks at three o’clock because you’re only battling the 10-year-olds,” grins a middle-aged skier one bluebird weekend. A quick dip into the trees on the next lap validates his claim.

School ski programs and ski hills will likely undergo a variety of changes for large events and group activities in 2021, as the world adopts new procedures to mitigate the COVID-19 pandemic. Small hills will face challenges, likely larger than having 150 hot dogs for only 100 hungry groms. Summit Lake was one of the last ski areas still operating in 2020 after most large resorts were forced to close. With a standard local clientele they might have stayed open even longer, but the number of out-of-town visitors spiked significantly after lifts stopped spinning in Revelstoke, Nelson, and Kelowna, forcing them to re-evaluate the risk and shut down. Now, it’s unclear whether the 2021 season will entertain scenes like the one I witnessed late last February: 100 youth ski racers and parents, from as far away as Cranbrook and Rossland, competing and celebrating rural skiing at a small hill tucked away in the West Kootenay. Yet, there’s still reason for the community to be optimistic. Beyond new protocols designed to keep individuals physically distanced, there are deeper and stronger cultural ties in rural ski communities, and people will never relinquish support of the hills that raised them.

Between a voracious appetite for human-powered vertical and a dirtbagginess rivalling Fred Becky, Matthew Tufts avoids ski resorts at all costs; however, when he does cheat on his earn-your-turns morals, he prefers creaky T-bars to high-speed quads.

Related Stories

Why Locals Ski Naked in Golden, BC

Every summer, indecently exposed to the sun’s sizzle and with winter’s last vestige all but shrivelled up, boarders…

Why Do You Ski (or surf…or ride…or kayak…or…)?

An interesting little film here..the trailer for Lifted was released this past weekend at the Leavenworth Film…

Ski Your Ass Off

Winter is upon us. But as we look to the future, it's not a bad idea to drift back into the past. The glorious, super…

History of Ski Aerial Acrobatics

One of the most influential ski films of all time. Dick Barrymores documents what started freestyle skiing. From 1969…

Powder Highway Ski Bum at SWS

Chris Tatsuno has done an amazing job chronicling his Ultimate Ski Bum Powder Highway winnings. In this episode he…

Powder Highway Ultimate Ski Bum Contest

We had to post this simply because it features KMC Editor, Mitchell Scott, in his formal acting debut. The contest is…