Backcountry skiing has exploded in popularity. In the West Kootenay region, the sheer number of adventure-tourism tenures is causing conflict among users and instigating impassioned pleas from the public for the government to press pause on the process. Residents of one East Kootenay town have weathered that storm by developing a local multi-user approach of patient collaboration that has pushed — and literally altered — everyone’s boundaries. By Jayme Moye. Illustration by Ian Johnston.

ALEX ROSS HAD A KOOTENAY dream to offer guided ski-touring trips out of a yet-to-be-built backcountry lodge through his fledgling business, Fresh Adventures. He would helicopter a small group of guests into his chosen area and fill their week with unforgettable powder days, long evenings by the fire, good food, and friends. The steps from dream to reality seemed straightforward: First, Ross filled out an application for tenure, which would grant him permission from the provincial government to operate commercially on Crown land. Next, he placed two ads in the local newspaper notifying the public of his tenure application and soliciting feedback. That’s when “Kootenay scrutiny” smacked him in the face.

Ross, who is originally from Toronto, had unknowingly chosen a section of Crown land just north of Nelson, British Columbia, that included a relatively new recreation site called West Kokanee, which prohibits commercial use. It also overlapped with a hallowed locals-only powder stash near the south boundary of the region’s beloved Kokanee Glacier Provincial Park. Last March, when word got out on social media about the tenure application by Fresh Adventures, Ross experienced an intense backlash. He was inundated with hundreds of emails and Facebook comments opposing his business and berating his apparent disregard for local backcountry ski-touring turf and the disruption he would cause residents, wildlife, and the environment by using a helicopter to shuttle guests to his proposed lodge. Multiple industry partners cut ties with his business. Ross’s favourite ski buddy disowned him, forcing Ross, who lives mostly out of his van, to change his mailing address from that friend’s place in Nelson to another friend’s residence in Vancouver. “Suddenly, I was a leper,” Ross says, “the evil empire trying to kill everybody.”

The tenure process has become so divisive that numerous groups are trying to find their own solutions to address what they see as an overcrowded tenure landscape.

Tenure is a touchy topic in the Kootenays. Multiple tenure holders who already operate successful backcountry ski lodges declined to go on the record for this story because they’re afraid of Kootenay scrutiny. If they try to expand their tenure area because, for example, they’re trying to steer clear of a herd of mountain caribou or there’s demand to add a new operating season to their business — like mountain biking in the summer — their tenure addendum application must first go up for public comment. And it can get ugly. “I can’t go to the farmers’ market or a school event without someone unloading their opinion on me,” says one well-established local tenure holder, who wants to remain anonymous. “No matter what I say, I’m going to get crucified.”

The tenure process has become so divisive that numerous groups are trying to find their own solutions to address what they see as an overcrowded tenure landscape. But perhaps the best approach dates back to 1995, when a grassroots organization in Golden, British Columbia, became a model for creating policy at a local level; they developed a framework for a sustainable regional tenure system that serves everyone’s interest in the backcountry — and they enforce it with the support of the provincial government.

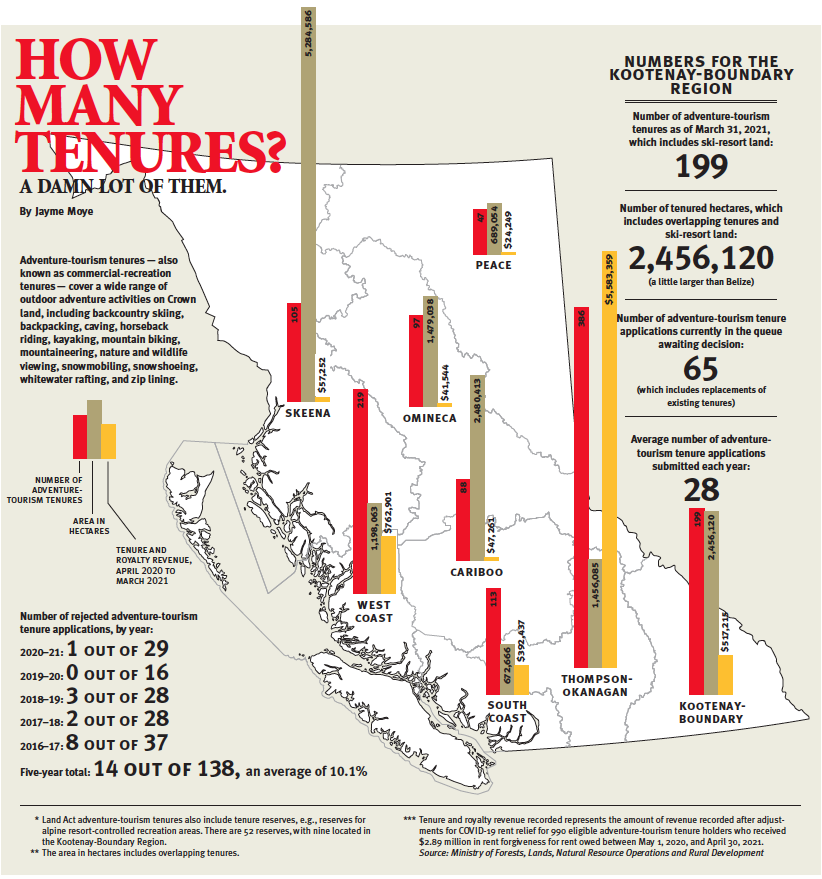

BRITISH COLUMBIA’S LAND ACT is a tool used by the provincial government to manage Crown land, which encompasses 94 per cent of British Columbia’s land, rivers, and lakes. The act makes it possible to grant tenure. In addition to commercial-recreation tenures (also known as adventure-tourism tenures), the Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development also grants tenure for a wide range of commercial activity, including forestry, mining, and hydroelectric power.

Adventure-tourism tenures span everything from guided nature walks to whitewater rafting to heli-skiing. Basically, if you want to earn money through outdoor recreation on Crown land, you can’t do it legally without holding tenure.

“I can’t go to the farmers’ market or a school event without someone unloading their opinion on me. No matter what I say, I’m going to get crucified.” — Local tenure holder, who wants to remain anonymous

The amount of land granted under tenure is based on the activity. If you’re a small, family-owned business offering human-powered ski tours out of a 14-guest lodge, like Valhalla Mountain Touring, your tenure will be sized accordingly — 3,865 hectares in this case. If you’re Canadian Mountain Holidays (CMH), the world’s largest heli-skiing and heli-hiking company, with 11 luxury lodges, you’ll hold multiple tenures across southeastern British Columbia for a combined 1.2 million hectares, which is larger than some European countries.

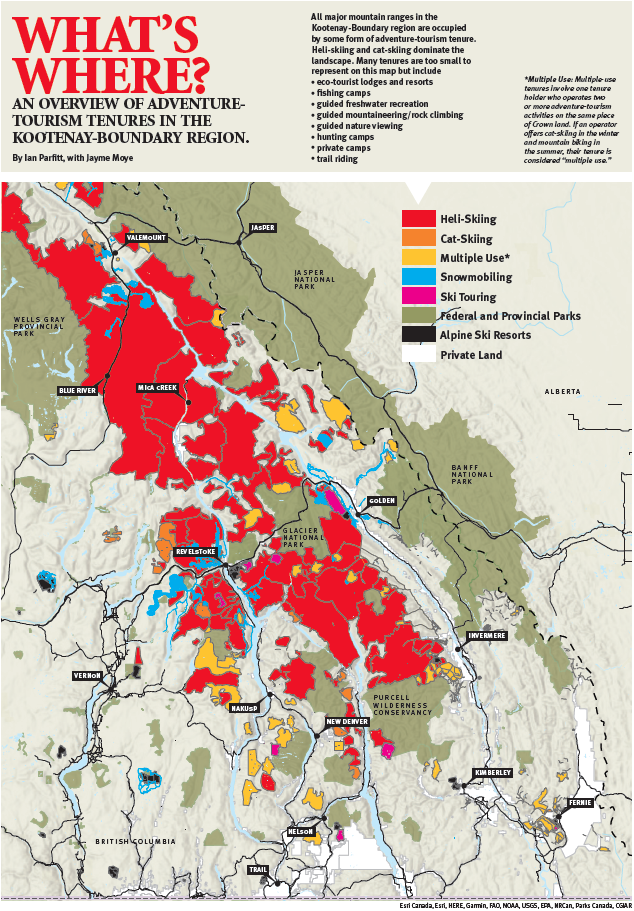

As of March 31, 2021, there were 190 adventure-tourism tenures in the Kootenay-Boundary region — the area starting at the United States border and extending north past Revelstoke to Kinbasket Reservoir. The region includes the Selkirk Mountains and the Purcell Mountains, as well as parts of the Columbia and Rocky Mountains. The Monashee Mountains fall just outside the region to the west. The Alberta border is the boundary on the east. In the past five years, the ministry has received an average of 28 new adventure-tourism applications each year, which includes replacements for existing tenures. They granted tenure for 90 per cent of those applications, or 124 tenures. Tenure length is typically 30 to 45 years.

The catchphrase “Kootenay scrutiny” was coined by long-time Nelson resident David Lussier, a certified mountain guide and founder of the well-respected company Summit Mountain Guides. In 30 years, he has watched the Kootenays go from a sleepy winter haven to the heli- and cat-ski capital of the world. “The bathtub is full,” he says. In addition to being at capacity, Lussier says one of the public’s biggest complaints is that new adventure-tourism tenure applications continue to come in for areas the public has already rejected applications for in the past. “It’s frustrating,” Lussier says. “The public keeps saying, ‘Hey we don’t want this here,’ and the government isn’t doing anything about it.” Lussier can think of at least three adventure-tourism tenure applications in the past decade from people trying to do the same thing that Alex Ross wanted to do with Fresh Adventures, in the exact same spot.

WINTER BACKCOUNTRY RECREATION is exploding in popularity. Avalanche Canada, which over the past five years has taught roughly 10,000 to 11,000 students each season in its avalanche-skills training courses, reported an unprecedented jump to 15,029 participants in 2020–21. Over the past 20 years, Lussier estimates a 500-per cent increase in participation in the Kootenay-Boundary region. There are a record 379 Association of Canadian Mountain Guides (ACMG) guides living and working in the Kootenays.With more people accessing the backcountry, many locals, like ski tourer and snowmobiler Pierre Kaufmann, the retired founder of the Valhalla Wilderness Program for kids, have been advocating that the ministry leave some Crown land uncommercialized. But Kaufmann feels that is not in line with their mandate. “Their job is to sell tenures,” he says.

At the end of the winter 2020–21 season, Kaufmann and other residents of the Slocan Valley formed the Valley Backcountry Society to fight for leaving the last bit of Crown land free from business interests. They were spurred to action by another tenure application, by independent guide Conor Hurley, for a powdery valley south of Valhalla Provincial Park. Like Ross’s application, it encroached on one of the few remaining places without a pre-existing adventure-tourism tenure.

Kaufmann and his cohorts understand that adventure-tourism tenures are non-exclusive and that a tenure holder cannot, by law, prohibit the general public from recreating

on the land. But there is a difference between theory and practice. And not because heli-ski operators are harassing local ski tourers by swooping their choppers unnervingly close, although Kaufmann has had that happen. It’s more to give the right of way to the people trying to run tourism businesses that market remote backcountry solitude. “The status quo is, generally, we stay away from tenured areas and respect their space,” Kaufmann says.

Whether or not that’s how the provincial government intended adventure-tourism tenures to work, it’s how tenure is largely interpreted by local residents. There’s also an ideology among some that the commodification of the backcountry should be avoided at all costs. “For a lot of us, we just want to go into the wilderness and leave our economic order and all our man-made structures [behind] as much as possible,” says Kaufmann.

But of all the user groups struggling with coexistence on Crown land right now, the biggest one might be wildlife.

The mission of the Valley Backcountry Society is to take select pieces of Crown land out of the tenure equation completely, such as the area south of Valhalla Provincial Park and another basin in the Valkyr Range, which shall remain nameless. (“I hope you don’t give specific references to those zones,” Kaufmann requested. “Locals will kill me.”) To do that, they’re lobbying Recreation Sites and Trails BC to enact Section 56 of the Outdoor Recreation and Forest Ranges and Practices Act, which enables the ministry to “establish, vary the boundaries, or disestablish interpretive forest sites, recreation sites and recreation trails on Crown land.” It’s one way to try and balance commercial interests, but the society’s ambitions have raised more than a few hackles in the guiding community. As Lussier explains, if a swath of prime winter terrain becomes a recreation site, independent guides can no longer bring clients there, which Lussier does not agree with.

Hurley thought he was doing the right thing when he submitted his Valhalla Ranges tenure application as an independent guide. To work in the Kootenays as a guide, you must either be hired by a big snow-cat or heli-ski operator or operate independently on park land (using the government’s permitting process) or Crown land (using the tenure process). Hurley chose the latter. According to the government’s Adventure Tourism Policy, for Crown land that has an adventure-tourism tenure already on it — and most do — independent guides are subject to “incidental use,” which involves notifying the tenure holder and sticking to “low impact” ski-touring activities, including “occasional motorized air access, carried out in a dispersed manner.” On Crown land that doesn’t have a competing adventure-tourism tenure already on it, independent guides who want to operate beyond incidental use, as Hurley hopes to do, need to apply for a tenure of their own. And, apparently, be ready to dodge bullets. Hurley received strong public criticism. He declined to comment for this story, and his tenure application is still pending.

“It gets complicated,” says Kevin Dumba, the executive director of the ACMG. “There’s definitely value in having certified guides on the landscape out there; we just have to see if we can find a way for everybody to coexist.” In response, the ACMG created the West Kootenay Working Group. Dumba hopes it will act as a communication bridge between guides and the general public and stave off additional conflict and potential ill-will. Some of the most opinionated players are part of this working group, including Lussier and Kaufmann, who don’t often see eye to eye.

The owner of Valhalla Mountain Touring, Jasmin Caton, was upset because she recently learned that a slope containing one of her business’s landmark backcountry ski runs was about to be clear-cut.

Current tenure holders also worry about coexistence, but from a different vantage point. This past summer, the owner of Valhalla Mountain Touring, Jasmin Caton, was upset because she learned that a slope containing one of her business’s landmark backcountry ski runs was about to be clear-cut. Tenures are non-exclusive, remember, which means they’re also shared among industries — in Caton’s case, with forestry. “It’s frustrating,” she says. “It feels like everything is set up to support and facilitate those more extractive industries.”

But of all the user groups struggling with coexistence on Crown land right now, the biggest one might be wildlife. The Kootenays encompass large tracts of undeveloped land, making it home to one of the most diverse and dense populations of large animals — like grizzly bear and caribou — in North America. Local environmental groups are concerned that the current tenure process doesn’t account for the cumulative impact of the ever-growing number of commercial and industrial tenures on Crown land, combined with the rapidly increasing amount of recreational use. Environmentalists have also pointed out that most of the region’s national and provincial parks are now completely encircled by adventure-tourism tenures, which could be negatively affecting critical wildlife corridors that connect protected land.

The government’s land-use plan for the Kootenay-Boundary region is from 1997, and Butler and Raynolds believe it’s woefully outdated, to the point of irrelevancy.

Who speaks for the wildlife? Kimberley, British Columbia-based Wildsight monitors every adventure-tourism application and makes science-based recommendations during the public comment process. And according to the provincial government, all tenure applications are referred to the ministry’s regional wildlife staff, who have expertise about the nature and scope of local wildlife and its habitat. Sometimes this results in change, like when the Campbell Icefield Chalet, on the west slopes of the Rocky Mountains, added a wildlife mitigation plan to its application for summer usage in an area that contained critical rearing habitat for grizzly bear cubs. But Wildsight Conservation Officer Eddie Petryshen says it often falls on deaf ears. “We have the science now,” he says. “We know things about grizzly bear and wolverine, but the province’s guidance around those things hasn’t changed since the science came out.”

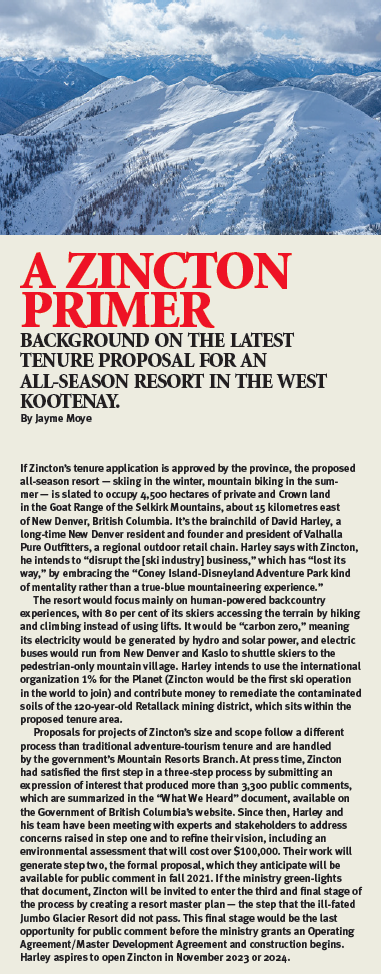

One of the most environmentally contentious areas in the Kootenays is the stretch of Crown land surrounding Highway 31A between New Denver and Kaslo. With Goat Range Provincial Park to the north and Kokanee Glacier Provincial Park to the south, it’s an important corridor for large and small mammals. It’s also classic Kootenay ski terrain: not too steep and oh so deep. As such, it’s densely packed with adventure-tourism tenures — 11 in total — which are held by some of the region’s most popular winter outfitters, including Retallack and Stellar Heliskiing. Last winter, when an expression of interest came in for Zincton (see sidebar), the first step in a three-part process to build a new ski resort within this area, environmentalists called it a step too far for wildlife. Zincton’s application prompted a local non-profit, Wild Connection, in partnership with the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative (Y2Y), to demand a moratorium on all new adventure-tourism tenures and the expansion of any existing ones until a land-use plan can be completed for the area.

“It’s the lack of government planning and management that’s actually at the heart of all this, rather than the tenure process.” — Dave Butler, director of sustainability, CMH

“There’s a lot of people feeling like the solution to managing all the conflict [on Crown land] is to have a good planning process,” says Nadine Raynolds, a Silverton, British Columbia-based program manager with Y2Y. “I think in this situation you actually have a lot of common ground.” She could be right. Of the 21 people interviewed for this story, both on and off the record, no one was opposed to land-use planning. In fact, most were vehemently for it. “It’s the lack of government planning and management that’s actually at the heart of all this, rather than the tenure process,” says Dave Butler, director of sustainability for CMH. “Tenure is just one of the tools that’s used to make things happen on the landscape.”

The government’s land-use plan for the Kootenay-Boundary region is from 1997, and Butler and Raynolds believe it’s woefully outdated, to the point of irrelevancy. Vera Vukelich, a manager of land policy and programs at the ministry, says creating new land-use plans is a big priority, and in 2018, the provincial government committed $16 million to work collaboratively with Indigenous governments, communities, and stakeholders to modernize land-use planning.

But ending the conflicts over powder in the Kootenays is not at the top of that land-use list, or even on the current list. “The BC government has been engaging with Indigenous governments and stakeholders to identity high-priority project areas,” says Vukelich. There are five projects currently underway across the province, and the two in British Columbia’s Interior are near Merritt and Fort St. John.

Here’s a compelling point: if the government does not prioritize your region, land-use planning can happen purely among citizens and then be proposed to the provincial government after the fact. That’s how it’s been done in Golden, Revelstoke, Cranbrook, and, most recently, in the Valemount area. While the plans are not legislated in all cases, the government has committed to following them for the purpose of providing resource-management direction on Crown land. The plans are also typically shared with aspiring tenure applicants before they put in an application, and the ministry refers to the plans when making decisions about which tenure applications to approve. “The land-use plan they did in Golden is landmark,” says Lussier. “They got everybody on the same playing field. It’s amazing what they did.”

During the 1994–95 winter in the Golden area, heli-skiing operators and snowmobilers were at each other’s throats because being in the backcountry together was getting dangerous. A few of the key stakeholders begrudgingly formed the Golden Backcountry Conflict Resolution Committee. They honed in on the most contentious area — a 200,000-hectare expanse — and started hashing out what type of activity, if any, made sense for each drainage. It took them four years and a lot of ripped-up maps, but they completed their plan in 1999 and presented it to the provincial government.

Local environmental groups are concerned that the current tenure process doesn’t account for the cumulative impact of the ever-growing number of commercial and industrial tenures on Crown land, combined with the rapidly increasing amount of recreational use.

At that time, the ministry employed multiple land-use planners for each region, two in Golden alone. Darcy Monchak was one of them, and he was assigned the task of formalizing the work of the grassroots committee and then expanding it to include all one million hectares of the Golden Timber Supply Area. Monchak gathered more than 50 people across 10 different sectors, including forestry and environment, sat them down together over “tens and tens and tens of meetings” and created the Golden Backcountry Recreation Access Plan. The group mapped every single drainage and wrote detailed descriptions about what type of land use was permissible and what wasn’t. When they finished, in 2002, Monchak, who has since retired from the government, says they’d managed to come to a consensus for the majority of the area, about 90 per cent. For the remainder, they agreed to let the provincial government decide. The ministry approved the landmark plan in 2003.

Today, a volunteer advisory committee keeps the access plan going. Chair Jason Jones doesn’t mince words about maintaining a functional land-use plan among potentially warring user groups. “We definitely have some difficult conversations, and we have to make some difficult decisions,” he says. Part of what helps the group stay cohesive is that the 10 sectors involved have been there since the beginning, and some of the representatives, like Butler from CMH, are original members. “There’s a lot of respect for the process, and people are in it for the long haul,” says Jones.

Precisely because local residents are so passionate, Monchak believes the West Kootenay is in an ideal situation for grassroots land-use planning — the kind that will stand the test of time and become a revered process. “Without the local committee keeping the plan alive, I don’t know where it would be today,” he says. “The reason the Golden plan succeeded is the committed members of the community here.”

Jayme Moye is an award-winning journalist based in Nelson, British Columbia. She hopes that writing this story won’t negatively impact her experience at the farmers’ market

Jayme Moye

Jayme Moye is an award-winning writer who specializes in stories about travel, mountain sports and culture, and pushing the limits of human potential. Her freelance work regularly appears in Outside, Canadian Geographic, National Geographic, and Condé Nast Traveler, among others. She is a Senior Writer with Kootenay Mountain Culture Magazine.

Related Stories

Take Part in the Smart Kootenays Challenge

Columbia Basin communities are looking for your input on how to make the region’s coveted lifestyles even more…

Powderwhore’s “Choose Your Adventure” Trailer

Despite the underwhelming winter of 2011-12, in which snowfall reached near record lows and unstable avalanche…

Summer 06 – The Four Points of Adventure

For centuries human beings have broken complex realities and concepts into groupings of four called quaternities.…

How 3D Printing Is Changing Adventure Sports

From lab to cash till, summit to toe, 3D printing is gonna change what adventurers wear and where they buy it. By Ryan…

Alien Encounters in the Kootenays

From audio anomalies to celestial orbs, there is no shortage of Kootenay UFO sightings. Are they hallucinations?…

Fly-Fishing in the East Kootenays

After a couple of bad breaks, an upstart East Kootenay angler learns the river's ropes and finds revival in the…