On January 7, 2020, Rebecca Hurlen Patano was caught in an inbounds avalanche at Silver Mountain Ski Resort in Kellogg, Idaho, the same one that took the lives of three other skiers. She was one of the ones who survived. This is her story.

Early on the morning of January 7, 2020, I took the 30-minute gondola ride up to Silver Mountain Lodge, where I met Ken Scott in the locker room located on the lower floor. We had not planned on skiing together that day, but I knew on a big snow day, if I arrived early, I could find one of my ski buddies and have a partner to ski with. I rarely ski big snow days alone, preferring the company of a friend, for safety reasons all veteran skiers understand.

We got out on the slopes and saw that Chair 3 was not operational. Good thing we did not ski down Collateral to get first tracks. We skied on toward Chair 2, making several quick runs to get a feel for the snow. It was heavy, but untracked. There was a lot of excitement between us and others on the slopes about how much new snow had fallen.

After skiing most of the runs on Chair 2, we headed towards Chair 4, skiing from the top of Kellogg Peak to 4, hitting The Ridge and dropping into a run called Bootlegger. About half way down the run, Ken took a fall and did a double eject out of his bindings. That rarely happens. I waited above him until he got his skis back on – giving me time to catch my breath and give him shit about his binding settings. We can do that with each other: banter, like siblings. We know each other’s limits and like to tease.

Ken skis a lot. Like, every day a lot. I ski on occasion when there is new snow during the week, and on weekends. “Some of us must work for a living” is my line. Although I still love to ski, I got my days in when I was younger. Growing up skiing in the North Cascades and then ski bumming in Utah, I had several 100+ day seasons. Some years, after the local resorts closed for the season, I would travel to different mountains – hiking and chasing the snow – during a time when all my belongings fit into my car. As long as I had a pair of boards and some duct tape to repair my ski pants, life was good.

That was 25 years ago. Now, I settle for skiing at Silver and other mountains nearby. My dream of having a more accomplished skiing resumé faded long ago. The friends I’ve made at these local mountains have always included me on the few days a week I get to play with them. Skiing with my friends feeds my soul. I love our ski posse and always look forward to skiing with them. With easy access to uncrowded runs and fresh tracks, I can ski and be a business owner. But a ski bum at heart I remain.

After Ken got an earful from me and put his skis back on, we noticed another skier popping out between the trees near us. Recalling that they had cut some new terrain between Bootlegger and Moonshine, we planned to go up Chair 4 to try and find the new gladded area and get some more fresh tracks. The snowpack was getting heavy, and the visibility variable. Skiing the trees would be a good choice.

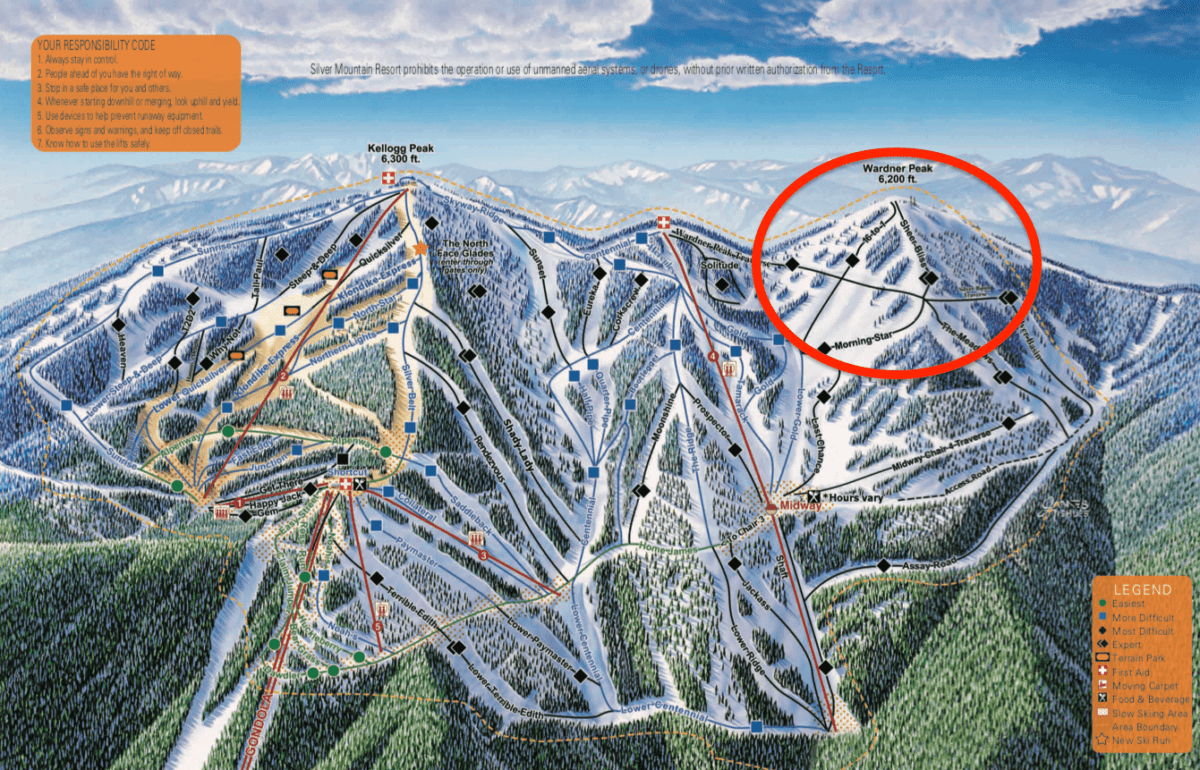

At the top of Chair 4, we noticed that the access to Wardner Peak Traverse was open. I said, “Let’s do the traverse instead,” so we both turned hard right off the chair. I saw many skiers and riders, who had already seen the rope drop and were headed to the entrance of the Traverse, or the hike up Wardner Peak. Ken and I quickly maneuvered past them, gaining speed on the glide down towards the traverse. I passed a few more riders on the glide – thinking “thank you” to my ski tuner’s wax choice. My new Faction skis were running fast, and I was loving the way they were handling in the fresh snow. As we approached the traverse entrance, I noticed four to six riders had already started the hike up Wardner Peak. This was the first time the rope had been dropped for the 2019-20 season, and everyone was waiting for that part of the mountain to open.

I entered the traverse first and Ken was right behind me. Fifteen to twenty feet in, I saw a line of skiers about 50 feet in front of me. Not wanting to que up and lose momentum, I stopped on a small rise to observe the situation. We were too far into the one-way traverse to go back, and the line of skiers was moving slowly. I noticed another male skier had now stopped behind Ken. I called out to them both. “I’m going to hold up here. We have a line ahead of us and it’s not moving fast.”

Both yelled back – “okay” in agreement. The last thing I wanted was to have them think I was not charging hard enough on the traverse. After 20 years of skiing at Snowbird, Alta, and Park City, this has been ingrained into my skiing style (and double so as a female skier). Move fast or get out of the way. There are words skiers get called for skiing slow on a traverse, words I have used on this very traverse, as the access to Wardner Peak terrain has become inundated with inexperienced skiers who don’t know how to move efficiently along the long trail that accesses acres of advanced skiing.

Once the line of skiers reached the first open area, a man, outfitted in vintage gear, descended the short treeless shot, whooping, and waving his arms in the air. As he wiggled some turns, I called out, “Have a good run!” It was fun to watch him. But I knew this shot is very short, with a run-out at the bottom that is not worth the effort. Right up ahead of us lay a huge open face with much more vertical to ski. His obvious enjoyment was contagious and soon, two or three other skiers jumped into the run after him. I was now much closer to the front of the line and all that untracked northwest powder.

Ahead of me I could see who was breaking trail and it was not the ski patrol. It was Warren Keys in his tattered mustard-yellow jacket. I have seen Warren on the slopes for many years. We don’t know each other well, but know of each other, like a lot of Silver Mountain skiers. I regularly see them in bounds and recognize their tracks out of bounds. Warren was no stranger to this traverse, and Ken and I both commented to each other that no ski patrol had been here first. The traverse had not been cut, and yet the area was open. Ken mentioned to me that it was the earliest in the season he had been on the traverse. I said, “I think it is late in the season to be opening it”. There is always a lot of talk about when parts of the mountain will open. I was surprised it was happening that day, and excited we had hit the timing just right.

Now there was time to relax, to observe as we traversed ahead, one skier at a time. The snowpack was thick, but not too wet. The uphill side of the fresh-cut traverse was above the knee, up to mid-thigh in depth. The mountain had reported 16” of new snow. I saw the small, bomb-triggered slide above us; a bit of debris, not trailing very far into the run-out, and a few snow cookies. I stomped on the uphill snow, widening the traverse, packing the snow down under my skis as we moved along. Warren, an experienced skier, was making progress and never slowing the pace.

Several more skiers queued up behind Ken, everyone chomping at the bit. Some skiers in front of us skied off the traverse, through the trees, then turned left onto the open run “16 to1”. Two others, behind Warren, dropped off the traverse onto the run, naturally veering left to ski across the face. Someone called out, “Ski the fall line!”

I was about a third of the way across the traverse, only a few skiers away from Warren, still breaking trail. One guy, Bill Fusack, looked back at me as I closed the gap. We acknowledged each other with a smile and a nod of the head. Excitement was in the air:, first tracks of the season down “16 to1.” Visibility was deteriorating, as clouds and fog settled in around us, but below lay an open snowfield, with only a few tracks. Now it was our turn.

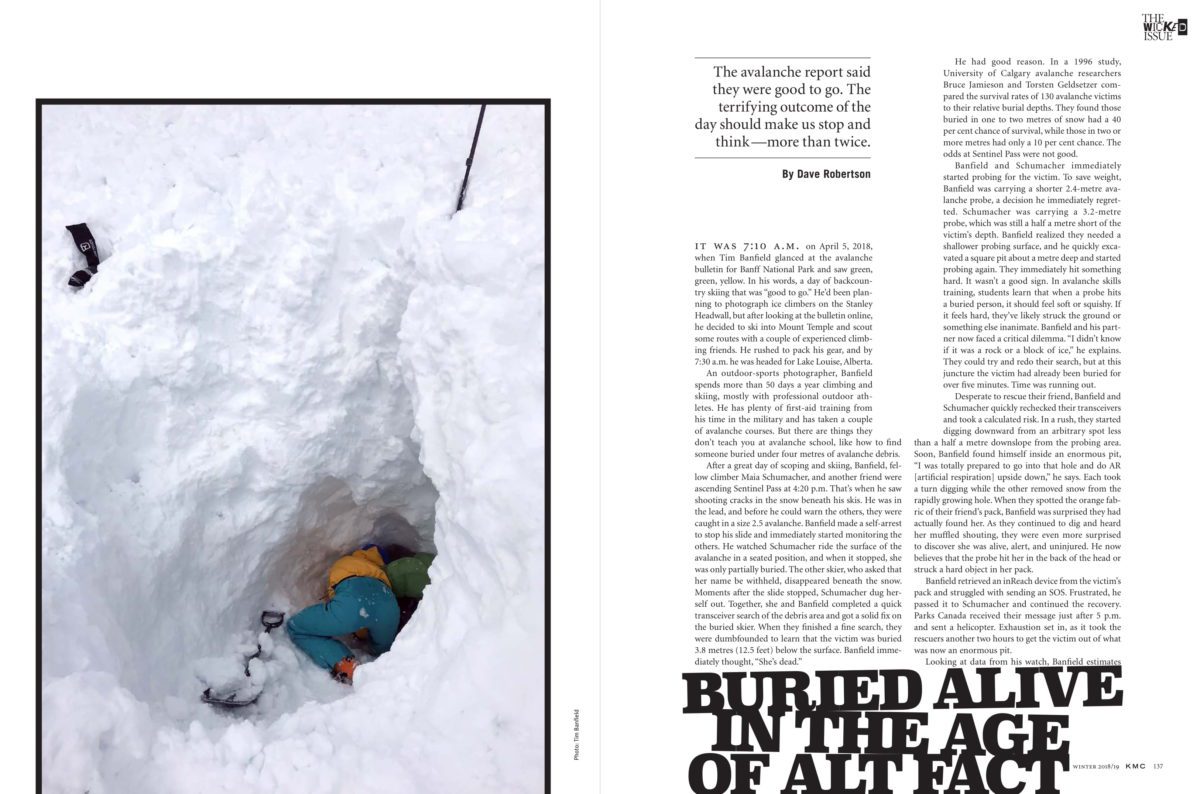

I called up to Warren to see if he wanted the first shot – no reply. I turned to Ken, and said, “How about here?” He nodded. I unweighted my skis and turned right, dropping off the traverse onto the run. I made one turn and saw a shape under my boots: a small slab of snow. The dark grey edges were almost 4” in depth. I never saw a crack or heard a release, but I knew it was an avalanche.

I called out, “Heads up! Slide!” I could just hear Ken yell back, “This is happening!”

Instantly the snow under my skis and all around me turned to cottage cheese, undulating and heaving downward like a waterfall spilling over a cliff. The snow was sinking, but rising in a wave, all at the same time. The thought of trying to ski it out flashed through my mind: completely unrealistic. This was no slough, so skiing out was not an option. I was still standing, in a skiing position, but the snow was moving very fast under me, carrying me down the mountain.

And then, a moment later, I was being pushed down, the backs of my skis covered by the snow descending the mountain. I thought to myself, “I am being driven down.” My ski poles, heavy, were dragging under the snow. I pulled my hands up in front of me, releasing the weight of the snow from my baskets. “The avalanche is surrounding me, sliding quickly past me, sucking me down.” The realization comes faster than words or thoughts.

My ski tips were somehow being pushed upward. The snow trap at the bottom of the run was filling up with slide debris, and in this moment I realize I am caught in the middle, simultaneously being pushed up by the snow piling up under me, and pushed down by the snow sliding behind me.

I am overtaken by snow. It encloses me, moving quickly up my back, and over my shoulders, heavy against my neck. It fills the space in front of me and piles up around my thighs. Then it rises in front of me, narrowing the view through my goggles. I hear myself say, “No, No, No!” as the snow engulfs me. Fear, thoughts of my family – my children, my husband, sisters, parents – I am scared to die this way.

And then everything stops moving. The sound is like a train screeching to a slow stop. A terrifying metal-on-metal grinding, but with more force than any man-made sound I know. The snow has stopped moving. And I am alive. I am breathing.

Compressed in a tight skiing squat, my skis still on, tips jutting upwards. The snow is covering my knees, it is piled loosely around my hands, still held tight near my chest. Behind me, snow is around my neck. The view in front is of piles of snow. I have never before been so buried alive, and I know immediately I am in a very serious, large avalanche. I think again of my family. I am not going to die here. So I get moving.

Quickly, I push my head back against the snow and look over my right shoulder. About 10 feet behind me I can see Ken’s hand, and his ski pole extending upwards through the snow, waving in large circle’s. I call to him, and I hear him call back. I look down the hill to my left about 15 feet in front of me: I see the backside of a black helmet. It is Bill, the man in front of me on the traverse. His bright eyes and white bearded smile are now covered in snow. I call him. I hear his voice yell, “Help, help me!” Not frantic, but shaken. A fear-filled voice calling for help.

I see another person at the bottom of the slide path. It is Warren. He has passed by me, carried by the slide, and is now down at the bottom, 50 feet or more below me, to my left. Standing upright he is buried up to his chest, but he too is alive. He is moving. I have identified the four of us as the only ones involved in the slide. – this will later become confusing for me.

In rapid movements, I push the snow away from my chest with my hands. Then with more effort, I pull my right leg upward to free my ski. But my right knee shoots with pain. This is a bad move. I realize it is going to be harder than just kicking my skis out of the snow and standing up, a move I have done countless times after a fall in deep snow. With effort and determination, I scrape more snow away to uncover my thighs, knees, shins, and bindings. I am so compressed that my boots and ski bindings are tucked very close under me. I use my right pole to release the binding, stabbing at it through the snow. I then remove my right pole strap and switch sides to release my left binding. I am moving fast, with unusual energy and power. I am not aware of being afraid. I remember only thinking that I must get to the others and get them uncovered from the snow. Fast.

Grabbing my skis at the tips, I use them to pull myself out of the encasement of snow. I push against the shovel of the ski to leverage the skis to pop out. I know I need these skis as a tool to dig with. The only tool I have. I turn right to look at Ken. He is still waving, his voice calm, and consistent. I will go to him first; he is my ski buddy. I look down the hill and to the left, towards Bill, and hear his voice. I am aware of making my first conscious decision; everything else so far has just been survival-motivated moving. I am choosing what decision to make right now and I consciously decide to move away from Ken, downhill towards Bill. (A decision that possibly saves my life and the lives of two others). I hold my skis in each hand, laying them flat on the snow for stability, crawling on my knees, 15 feet down the steep uneven avalanche debris, toward Bill. Placing my skis on either side of his helmet and kneeling behind him, I bend over him to swipe the snow from the front of his face.

Grabbing my skis at the tips, I use them to pull myself out of the encasement of snow. I push against the shovel of the ski to leverage the skis to pop out. I know I need these skis as a tool to dig with. The only tool I have. I turn right to look at Ken. He is still waving, his voice calm, and consistent. I will go to him first; he is my ski buddy. I look down the hill and to the left, towards Bill, and hear his voice. I am aware of making my first conscious decision; everything else so far has just been survival-motivated moving. I am choosing what decision to make right now and I consciously decide to move away from Ken, downhill towards Bill. (A decision that possibly saves my life and the lives of two others). I hold my skis in each hand, laying them flat on the snow for stability, crawling on my knees, 15 feet down the steep uneven avalanche debris, toward Bill. Placing my skis on either side of his helmet and kneeling behind him, I bend over him to swipe the snow from the front of his face.

It is then that I am hit by the second release of the avalanche.

Totally unexpected, the slide hits me forcefully from behind, knocking the wind out of my lungs. I am tossed over Bill’s helmet and slammed onto the snow, tumbling with the slide down the mountain. I come to rest head down, partially buried, again. Most of the snow has gone over the top of my body, sliding beyond me, descending the entire run, piling up around the trees at the bottom. I am in pain, shocked, and confused.

Instinctively pushing up onto my knees, I rise to my feet, in pure survival mode, ready to fight for my life. The adrenaline coils in my veins. “What just happened?” I was so stunned by the first slide, it never occurred to me to watch out for a second. Logically, I know there is often a second release,

but there is no logic in my brain. Just pure reaction and instinct.I am confronting the most serious threat to my survival ever, and I am singularly focused on it. That, and on getting others out of the snow, which is somehow completely linked to my own survival. My awareness of everything around me is reduced to this single thing. Survive.

I look downhill toward Warren. I am about fifteen feet closer to him – I think – and I can see through the snow, left billowing by the slide, that he is buried again, even higher this time, up to mid-chest. We are united in disbelief. I yell to him, “You okay?”

“Yes, Okay, And you?”

“I’m okay.” We are alive. Again.

Turning, I look uphill. I yell out loud, “NO!” In my mind I am thinking, “We are totally fucked.”

The two people I saw a moment ago are gone, completely covered by the new snow. The view is horrific. I cannot see Ken’s hand, or ski pole. I cannot see Bill’s helmet or any part of the hot pink skis I just set there. I cannot see any sign of life. No movement. Nothing but snow. Worse than that, the entire landscape has changed. There are huge mounds of snow where there were no mounds a moment ago; so much snow has moved. Everything is different. It is a scene of terror. People are buried alive.

I am frantic now. A few moments ago, I was on an opened traverse, on a named, patrolled ski run on the front side of the resort. Now, I have nothing. No poles, no skis, no sight of survivors. What just happened?

I unzip my coat, grab my phone, and make three calls in what I later note was one minute and 47 seconds. Speed talking.

I call Earnie, a ski buddy and instructor who works with Silver ski school and knows I am skiing this day. He answers with a voice filled with joy and enthusiasm: “Ruby!” He shouts my nickname into the phone. I respond firmly, though in a shaken voice, “There is an avalanche on Wardner. Ken is buried. Bring everything and everyone. Now.” Earnie – “What? Where?” “Near the trees, skiers right, on 16 to1 off Wardner Traverse. The traverse slid.” Click.

I call Joan Wroe, another buddy and longtime volunteer patroller, who I had taken a run with earlier that morning. “Hello?” “Joan, an avalanche on 16 to1. There are two buried and Warren is a partial burial. Bring help. Don’t take the traverse.” Click.

I call Terry, my husband of 32 years. When he answers, I tell him I have been in an avalanche and I am ok, but Ken is buried. I hear his breath get sucked out of him, and I can feel the shock in his silence. I tell him again I am ok, and not to call me back. That I will be in touch when I can… click.

I have just delivered news that will change people’s lives. I regret my abrupt words but at this point there is no time for niceties. Later, I will learn that Terry called the ski resort and reported the avalanche. He informed them his wife was buried in an avalanche off Wardner Peak and to please call him back once they had information about her safety. (He is still waiting for that return call).

I am frantic now. A few moments ago, I was on an opened traverse, on a named, patrolled ski run on the front side of the resort. Now, I have nothing. No poles, no skis, no sight of survivors. What just happened?

Putting my phone away, I look again towards Warren. He has made some progress in freeing his upper body, but he is a tall man and there is a lot of work to do to clear the snow around him, so he can release his ski bindings. Then a skier (Ron) arrives below me, cutting across the slide path from the right, having skied the trees along the side of 16 to 1. I yell to him: “Go get help!” Quickly, he skis away to report the incident to the chair 4 lift operators.

Turning uphill, I scramble up to the area where I last saw Bill and Ken. At least I think it is the area. I have to find them. I start to dig in the snow with my cold hands. Useless. The snow is a consistency impossible to dig in with no tools, and I am immediately frustrated. My body is filled with adrenaline and the fear of not doing anything fast enough.

Other skiers begin to arrive around the slide zone and one hikes up to me. He is wearing a royal blue jacket and black pants. I can see his hazel eyes reflect my terror. He takes his pole and removes the basket to convert into a probe – it’s taking so long – I know he is working fast, but my head is in hyper drive and nothing is moving as fast or efficiently as I think it could. Every moment is stretched into a time warp. I grab the pole out of his hand and start jabbing it into the snow. I am yelling, “There are people under the snow!” Help, get some help! We have two bodies buried! Help dig here. Now!”

A skier in a burnt orange jacket stands at the bottom of the slide debris, way down by the trees. He is on the phone with 911 but is yelling up to me. He asks me the names and ages of the people buried. I cannot answer right and I get Ken’s name wrong. I correct my mistakes, and call out the first and last name and age. At the time I did not know Bill Fusack’s name, I just described him. But I only wanted to dig. I wanted the guy on the phone to stop interrupting me, to come help dig. (Later I realize he was part of the rescue – just not the go crazy probe in the snow part.)

Grabbing my skis at the tips, I use them to pull myself out of the encasement of snow. I push against the shovel of the ski to leverage the skis to pop out. I know I need these skis as a tool to dig with. The only tool I have.

Then the red coats of two ski patrol appear above us in the fog. Scared of another slide, Warren and I both yell, “Don’t come down!” We wave and yell. But they ski toward us. There is no other choice. They descend, and we hold our breath.

Ski patrollers Mike and Mira get their beacons out and proceed to sweep, asking me some questions. I tell Mike what I know – two people are buried – and my estimate of locations. I tell him one is Ken. Mike knows Ken and now his face grew even more serious. I ask if they had extra probes or shovels that we can use and they say, “More are coming.”

I grow more frustrated with each passing moment. Other skiers and riders start showing up. Some come from below, hiking up and over the tumbled mounds of snow. Some are coming from the side of the hill, some go to Warren to help dig him out. The clock is ticking. It feels like hours have passed. I am head down, probing a useless ski pole into the snow. It barely reaches three feet but it is all I have, and I cannot stop. Until, I hear the whomphs – the unstable snowpack settling.

It is a sound so frightening it makes my heart stop. Every cell in my body registers immediate danger. My instincts tell me to move, now, but I cannot move. I can only pause, look up, and hope that no more snow hurtles down the mountain towards me. I put my head back down and return to probing the snow. I tell myself, “Focus.” Focus on my actions, so the panic does not take over. There are three huge whomphs within the hour.

(Later I learned that there was another slide on Morning Star, just one run over from us, and the terrain between the two had collapsed, but did not slide. The Wardner Peak slide measured almost 400 feet across by 900 feet long, and was 22 feet deep at the toe of the slide area).

My friend Joan arrives with other ski patrol and some more rescue equipment. We work to probe in a line, but do not have a rope yet to keep us straight. There are attempts to organize the rescuers but no one is leading, no one really listening. Every time a new ski patroller comes to the scene they ask, “Are there beacons on the skiers that are buried?” Every time I answer, “no.” (I did not know Warren was wearing his beacon that day). But inside I am thinking, “Why would we? It is an open, in-bounds run. A patrolled run. We are not skiing in the backcountry.

Then the red coats of two ski patrol appear above us in the fog. Scared of another slide, Warren and I both yell, “Don’t come down!” We wave and yell. But they ski toward us. There is no other choice. They descend, and we hold our breath.

Earlier in the season, I gave my beacon, probe and shovel away, knowing I was only going to ski the resort this year, assuming that, of course, I was going to be safe in bounds. I understand why they ask: to make sure the beacons are turned from “send” to “search” mode, to not interfere with the rescue. But I hear it as an accusation, implying we were not prepared. Adrenaline is twisting up my mind. I am short tempered. I am shocked at the situation I am in, frustrated with how long recovery is taking. But I continue to probe.

Earnie arrives on the scene with an arm full of 10-foot-long metal conduit poles, normally used for fencing. There are so many poles in his arms that he sinks into the snow carrying them up the hill. Finally, we have some more tools. I switch to a longer probe pole and jam it into the snow, all the way to my hands. It sinks eight feet down, not hitting anything. More people come to help, with probes and shovels in hand; there are people all over the mountain slope now. Still, it seemed chaotic and I wanted the ski patrol to lead us, organize us, tell us what to do.

Then someone calls a strike, uphill from Warren but below from where I am probing. The location confuses me. I call to the rescuers digging there, “Do you see any skis? Are there pink skis by his head or anyplace around him?”

“No, skis!” they reply.

“How can that be?” I think. I know of only two people buried and one has my skis near him. Then I realize: there must be more people. More people are buried in this slide.

I move down the hill to confirm that it is not Bill and that my skis are not buried nearby. They pull snow from around the victims head and I see the lack of color in his face. I do not linger. I knew he did not look good, but there are two others to find and I must keep looking.

(Carl Humphreys, a friend to many and a fixture on the slopes of Silver, was the first skier found. He was worked on by several patrollers and then removed from the scene quickly. I never saw him during the avalanche and do not recall seeing him on the traverse, so I never even knew he was buried. Earnie had skied with him earlier that day).

The seriousness, the enormity of this slide is starting to close in around everyone on the hill. I call out loud, “We have two more bodies buried!” Mike the patroller responds, “What? Two more?” “Yes!” I am shouting. “There is a man right around this place, with a black helmet and my skis are near him, and another man, Ken, is over here!” I point, indicating the two locations, which are now distorted for me, with so many people standing all around.

The man in the orange coat on the phone calls to rescuers: “Forty minutes have passed!” This time stamp causes me to buckle. So much time, I am so frustrated. We still haven’t found the two people I knoware under the snow. My mind is hyper focused on only one thing: find them.

But I pause to call Terry, “We haven’t found them yet. You need to help. Please, put a bubble around them: see them with air going into their lungs. Visualize them getting air. And pray,” (which was an unusual request from me). As I speak to Terry, I try to imagine Ken and Bill under the snow, but I cannot slow my mind down enough to concentrate on them. I hang up the phone. “I must keep searching,” I think, and return my attention to the scene. The weather has momentarily cleared a bit, and I can see the unusual landscape being explored by all the rescuers: the snow is chunky and hard to walk on. The sky and the snow are both the same color grey.

Suddenly a second strike is announced. Everyone in the area switches from probes to shovels and they dig down into the snow, more than five feet, where they discover the black helmet of Bill. My skis are buried next to him. I do not help in Bill’s rescue; many others are there digging the snow out from around him. I only hope he is still alive.

“Ok,” I think, “now I have Ken’s location dialed in.”

I move up the hill as quick as I can to the place I last recall seeing Ken, his hand waving out of the snowbank, doing circles in the air. Mayday circles. With Joan to my right and Earnie to my left, many rescuers, who were not on the other two strikes, form a probe line led by a female patroller. Standing above us she calls: “Probe right! Probe center! Probe left! Step forward!”, repeating this 2 times. We lose momentum and some people are taking huge steps. The line looks like a jagged saw blade.

My frustration is amplified by adrenaline and I feel we are in slow motion. I want everything to be faster. People are buried under the snow. Move faster, dig faster. Then Joan yells out, “Probable hit!” She is not sure if the strike is Ken. The lead patroller shouts back, “Leave the probe in place!” Everyone nearby probes around the area she has marked in the snow. I am relieved, hopeful: another strike. I trade my probe for a shovel and start digging. Everyone starts digging.

I am on top and to the left of the hole being formed, digging at an awkward angle, just digging to keep the snow from falling into the huge hole that is forming. We need more help. I am yelling to get more people to make a shovel line. Someone tells me yelling is not helping… So I take a step back from the hole, toss my shovel to someone below me and take a long breath.

None of the rescuers around me even know I was in the avalanche, along with these men; that the person we are digging out is my ski buddy. I am deranged with stress, and exhaustion. I have been moving non stop the entire time. Fifty minutes? An hour?

The ski patrol and others around Ken are all bent down on their knees, removing snow by the shovel full, moving fast, but careful not to put a shovel in his body. Then they find his hand, still held up in the air, frozen in a wave. Ken is found. Ken is alive. And he is yelling. And yelling. He takes huge gulps of air, then yells some more.

(That dude talks loudly and often, and he was buried under nine feet of snow for 50 minutes, then comes out yelling like the crazy Canuck that he is. It seems no snowpack can contain him.)

Everyone around pauses, acknowledging the fear that had been inside all of us: of finding Ken not breathing.The fear is replaced by several loud claps and shouts in response to Ken’s voice being heard across the mountainside.

I call to him: “It’s ok, stop yelling! Save your breath.” I turn towards Earnie and we hold each other in a long, tight hug. I can slow down now. I can breathe too. We have found him, alive.

I call Terry and tell him the news. I take a few photos of the chaos around me, feeling guilty for capturing this horrific scene, like I am a traitor, filming instead of helping. (These pictures have been very useful. Giving us insights to parts of the story we did not recall during the rescue. Now, I and others are glad to have them as reference).

I look around. There are 30, maybe 40 people in groups on different parts of the slide path. This community of skiers and riders has stopped in their tracks, postponing their ski day, putting themselves at risk, to help be a part of the rescue. We would not have been successful without them. There are toboggans, snowmobiles, and a snow cat is crawling up the hill towards us. There are ski patrol, shovels and probes and first aid kits. There are holes in the snow. And there is so much snow.

I see Bill, being steadied by a ski patrolman, holding his arm. He looks disoriented, woozy, but very much alive. The snow pit around him is eight feet deep. The location where Carl was found is a vacant hole now. Warren is nearby, his mustard coat still visible in the low light. I don’t even know when he got un-buried and out of the snowpack. The scene is surreal.

Ken gets dug out and is placed on his back on the snow, a sled nearby to transport him. He is saying to the ski patrol, “Don’t collar me, I have been a ski patrol, I don’t need to be collared.” I move toward him, walking awkwardly around the hole and up to his prone body. I lean over him, and say, “Ken, let them do their job.” He sees my face and calls out my name. I realize that, even though I thought he had seen me already, maybe he did not totally understand that I, too, am alive.

He grabs me and pulls me to him, in the tightest, most gripping hug I have ever felt. How can he be so strong at this point? He hugs me for so long that my lungs and back begin to hurt, and then hugs me for longer still. He is alive and I am alive, and it is a relief to us both. Now others might understand why I was so frantic to get to these guys.

Just over an hour ago, I was the last to see them both. Ken is cold now, and shaking. I move to the top of his head and help the patrol to place heat packs on his body to warm his core. Ski patrol are softly palpating his body, to make sure his organs are not crushed. We struggle to get his gloves off and place the warm packs on his hands, then cover them with larger gloves – his hands are shaking so much that this simple task is almost impossible. It becomes too hard for me to see and be a part of this, as I realize how bad off he is. And maybe how messed up I am.

He asks to be sat up on the toboggan and a backpack is propped under his back. He asks not to be strapped in. As the patrol pulls him away, he yells out loud again and waves to the rescuers, his frozen hand reaching up in the air once more. They all yell back, wild with relief.

(Ken was found under nine feet of snow, after 50 minutes of searching. Statistically, we were performing body recovery. But that statistic never reached my survival-crazed cortex. I was only looking for my ski buddy, so we could make another turn, another day).

I take a step down the hill and am suddenly so exhausted that I need to hang onto a man’s jacket. He looks at me like I am crazy. I realize I am starting to lose my ability to function. I need to get off the mountain. I need to eat. I hang onto the sleeve of the jacket like a lifeline. “I need a hand,” I say. He nods, in what I hope is understanding.

Unsteady, I make my way down the hill to Mike (the first ski patroller on the scene) and we hug and cry a few tears of relief. My neck and back are seriously hurting, if not from the slide, then from strong skiers hugging me so tightly. After all that has happened, it feels just right.

Another ski patroller asks me, “Do you think there is anyone else buried?” I pause and consider this question. The words don’t come easily. “There could be more. I only saw two get fully buried and yet we already found three people. Yes, there could very well be more. My reply makes me physically sick.

Mike calls out to continue the search. They begin to organize another probe line. I wave to Warren, asking if he is ok. We look at each other in a new light: witnesses to this strange event – connected now by an experience neither of us would ever have chosen to have. I am still focused on the people I saw: Ken, Bill, Warren. They are all out of the snow, alive. And I am alive.

I locate my skis, stuck in the snow nearby, and look for my poles. I find only one. Earnie has agreed to ski with me to the lodge and he lends me his ski pole so I can better navigate my way down the slide debris, through the trees at the bottom of the avalanche. I am drained of strength and unstable, but can still ski. I just need to hang on a little bit longer. Talking out loud to myself, I say, “Come on, you got this.”

As we ride on Chair 4, I cannot look over to the right, toward Wardner Peak and the slide. I can only hang onto the center pole of the ancient double chair and hope it does not break down. (I already have one free cola coupon from sitting on a broken chair this year, and four from last year).

The snow has warmed and settled, and the skiing is extremely difficult. I curse the poor grooming. After surviving an avalanche, skiing should not be this difficult, just trying to get back to the lodge. I am exhausted by the magnitude of what has happened and the shocking facts of the day are seeping deeper into my psyche.

In the lodge I head to the patrol room, down the hall from the locker room where I started my day. I enter, searching for Ken. At first they tell me nothing, but when I let them know I was in the avalanche with him and I have his gear (and maybe I threaten to hurt someone if they don’t tell me where he is?), they let me know he is being taken down the mountain to the hospital on the old Jackass road. I turn and go, the patrollers seemingly glad to be rid of the disheveled, limping skier in front of them. I am again focused on finding Ken, so I return to the locker room, grab my gear and head toward the gondola to leave.

(It would have been beneficial for the survivors and helpful to the rescue efforts if we had been kept together, and debriefed. We had so much information in our heads, and with a few questions the resort would have had a fuller picture of the incident).

An instructor from ski school recognizes I am in shock and offers to ride down with me. He just sits with me and gently encourages me to seek medical attention for my hurt knee. But I am comparing

myself to others, rationalizing that I am not hurt that bad, that I was not buriedfor 50 minutes.

At the bottom, Terry is waiting for me. So is the sheriff. I mumble answers to his questions and give a brief statement. I see the pro-patrollers from other ski areas, and a rescue dog, getting ready to load the gondola and help with the search efforts. In this moment I am so frustrated with the events of the day, and with the entire mountain operation, I just want to leave this place and be with my family. I want to be held and to feel safe.

Terry drives me the short distance to the Shoshone Medical Centerin Kellogg. Administration staff shield me from the media and TV crews that have swarmed to cover the event. I am encouraged to get checked in so they can examine my knee. “No” I think, I came to find Ken. I don’t think I need any help. But I can see the concern in Terry’s face, and I agree to his suggestion, “Just let them take a look at you, it’s best.” Covered with heated flannel blankets, I relax into the warmth, and face the fact that I am now a patient, even though I came here to find another.

Terry makes calls to locate Ken, who is not here as I was told, but still on the mountain, in the lodge with Bill. I am trying to figure out how I made it down to the hospital before he did. Terry hands me his phone and I am finally able to speak to Ken. He lets me know he is okay. He has found a ride and will leave soon to go home and tell his wife Ruth what happened on the hill today. I am relieved, I can stop trying to find him. I talk to Bill: we make introductions, admitting this is the worst possible way to officially meet. He is full of gratitude. He is thanking me. I don’t think I deserve it.

The phone is passed to someone from Ski Patrol. Now, for the first time, having already heard from my friends that I am in the hospital, they ask if I am okay.

“Yeah, the doctor is taking an x-ray.”“I want to know about Carl,” I say. I feel disconnected, tired, but I need to know. When the facts are shared, the blankets are not warm enough: Carl Humphreys is confirmed dead.

Later that evening, after many more hours of searching, another body is recovered. Scott Parsons, from Spokane, lost his life in the slide. Two days later a third victim is located, Molly Hubbard, an Oregon resident. In total: seven buried, three deaths. Four of us are alive. All of us were on the Wardner Peak Traverse. The news is heavier to me than the snow that slid. I disconnect even further….

My brain takes weeks to return to full function. I am not able to speak correctly, I cannot recall names of people I am talking to, I cannot focus on more than one thing at a time. Everything I used to do easily now takes a lot of effort. I cannot move quickly, and objects moving around me are startling. Light hurts. I am hungry. So hungry. I cry when snow falls on our deck in the following days. I am afraid of snow. Was this going to be my life now?

During the first few days, Terry took care of me, making me coffee in the mornings and cooking for me. Friends brought gifts. I went to work and stumbled through, totally ineffective, trying to regain some type of normal. Terry and I met with Ken and his wife Ruth: two married couples hanging on to this new life, sitting in restaurants in a surreal fog. Hungry, worried, mad, grateful. We tried to share with each other what we were feeling. Later Terry and I hosted a dinner, cooked pizza in our wood fired oven to feed six guests: it was the first time the survivors of the avalanche and their spouses had all met each other.

Warren, Bill and Ken each shared their version of what had happened; then each partner recalled the fear of almost losing a spouse. We learned, we hugged and cried. United in this experience, we all spoke about feeling some form of survivor’s guilt. To survive is a blessing, but it is laden with weight, and with a question: why them and not me? It could have been any of us, or all of us. After dinner we lit a candle for the three skiers who did not survive, knowing full well that the small flame was inadequate, but not knowing what else to do.

I am so sorry. I never saw any signs of other skiers after the first slide, and certainly not after the second. I never knew they were there. If I had, I would never have stopped searching. I would not have left the mountain. Once you see someone get buried alive, you cannot stop searching, knowing they are down there, somewhere, under the snow.

My new reality was narrow, every day filled with simple acts: being awake, breathing, moving, trying to think like I used to. My brain used to be different; my life was so different. I kept going out, trying to find myself again.

I took a planned ski trip with friends who love the outdoors and encouraged me to feel again. I cried. I got scared, but I kept moving, kept feeling. I went for medical attention for my knee and back, the trauma stored deep in the tissues. I found mental health counseling. I kept going to work. Eventually I went back to the traverse at Silver and skied it with Joan behind me, in support. I questioned all of my choices on the day of the avalanche. But I accepted the gratitude showered on me from the survivors and from many friends. I have talked about the incident a lot, and I mean a lot: to Terry, to Ken, to many others.

What changes need to happen so a tragedy of this magnitude does not happen again? So that the lives that were lost on January 7th are not lost in vain? Our entire community has a story connected to this tragedy. So many people affected: the first responders, everyone on the mountain that day, Silver Mountain staff, all of the pro-patrol and volunteers who came from three states to help during multiple days of rescue and recovery. Our skiing community has had the shocking truth delivered to us: the danger of an inbound avalanche.

At night I have dreamt of being fully buried alive, feeling just the tiniest hint of what others experienced. I have woken fearful, drenched in sweat. And, after a long while, I have let snow fall on my face. Without fear, I have felt the cool wet lick of the crystals I love so much melt on my skin.

Related Stories

The Rebirth of Baldy Ski Resort

Mount Baldy, that definitive grassroots BC ski resort located near Oliver, has gotten a new lease on life. Here's the…

Ski Your Ass Off

Winter is upon us. But as we look to the future, it's not a bad idea to drift back into the past. The glorious, super…

Home Run

Where do you find your home?

History of Ski Aerial Acrobatics

One of the most influential ski films of all time. Dick Barrymores documents what started freestyle skiing. From 1969…

Powder Highway Ski Bum at SWS

Chris Tatsuno has done an amazing job chronicling his Ultimate Ski Bum Powder Highway winnings. In this episode he…