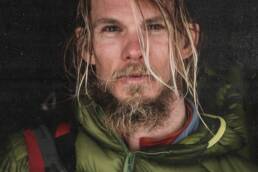

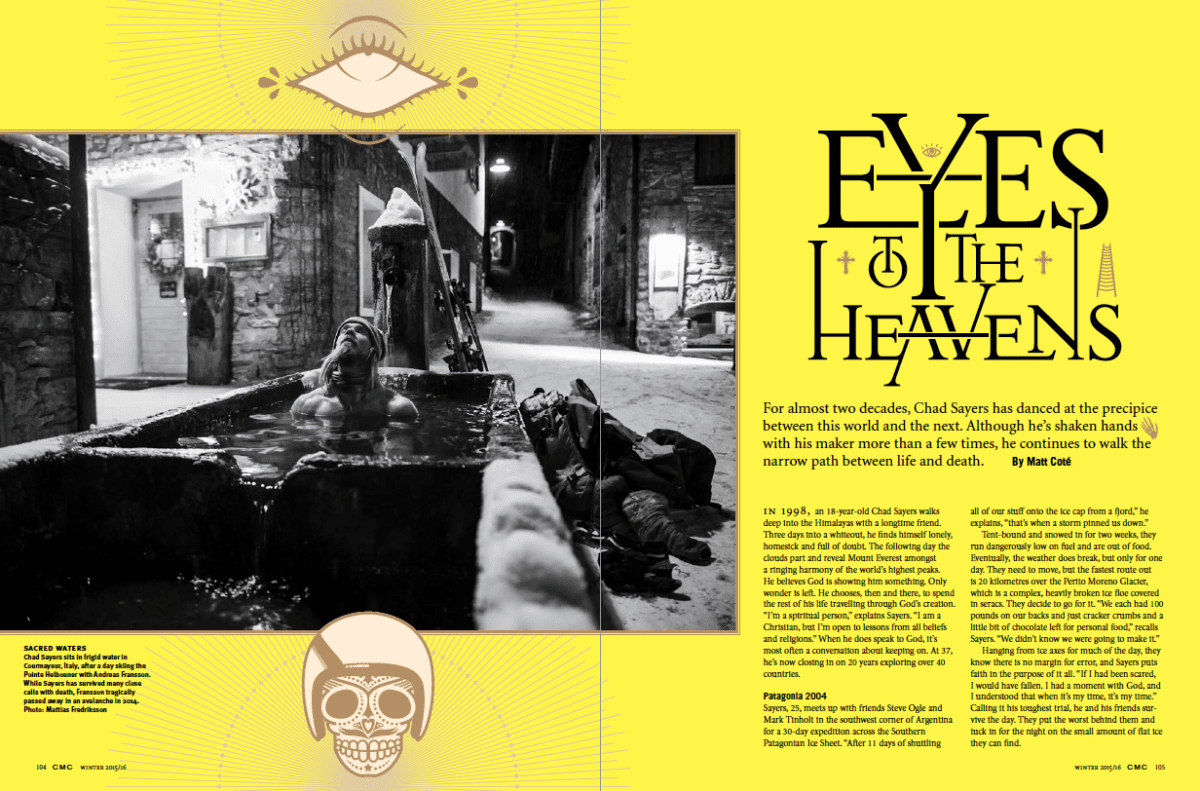

For almost two decades, Chad Sayers has danced at the precipice between this world and the next. Although he’s shaken hands with his maker more than a few times, he continues to walk the narrow path between life and death. By Matt Coté

IN 1998, AN 18-YEAR-OLD Chad Sayers walks deep into the Himalayas with a longtime friend. Three days into a whiteout, he finds himself lonely, homesick and full of doubt. The following day the clouds part and reveal Mount Everest amongst a ringing harmony of the world’s highest peaks. He believes God is showing him something. Only wonder is left. He chooses, then and there, to spend the rest of his life travelling through God’s creation. “I’m a spiritual person,” explains Sayers. “I am a Christian, but I’m open to lessons from all beliefs and religions.” When he does speak to God, it’s most often a conversation about keeping on. At 37, he’s now closing in on 20 years exploring over 40 countries.

Patagonia 2004

Sayers, 25, meets up with friends Steve Ogle and Mark Tinholt in the southwest corner of Argentina for a 30-day expedition across the Southern Patagonian Ice Sheet. “After 11 days of shuttling all of our stuff onto the ice cap from a fjord,” he explains, “that’s when a storm pinned us down.”

Tent-bound and snowed in for two weeks, they run dangerously low on fuel and are out of food. Eventually, the weather does break, but only for one day. They need to move, but the fastest route out is 20 kilometres over the Perito Moreno Glacier, which is a complex, heavily broken ice floe covered in seracs. They decide to go for it. “We each had 100 pounds on our backs and just cracker crumbs and a little bit of chocolate left for personal food,” recalls Sayers. “We didn’t know we were going to make it.”

Hanging from ice axes for much of the day, they know there is no margin for error, and Sayers puts faith in the purpose of it all. “If I had been scared, I would have fallen. I had a moment with God, and I understood that when it’s my time, it’s my time.” Calling it his toughest trial, he and his friends survive the day. They put the worst behind them and tuck in for the night on the small amount of flat ice they can find.

Soon enough the storm rolls back in, but they’ve made just enough headway now; they’ll be able to cross the terrain that’s left in the foul weather — just. “If we had been one day behind,” says Sayers, “there’s no way we’d have been able to cross. We would have died trying.”

From Sayers’ journal: “Often I try to figure out life and why certain things happen. But the older I get, I realize that it’s all part of a story that has already been written.”

Alaska 2010

Still recovering from a string of injuries that started with a near-career-ending crash in a freeskiing competition in Utah years earlier, Sayers gets the call every ski athlete is waiting for: to shoot in Alaska.

Only days after considering hanging his skis up for good because of chronic pain, he’s in Haines, Alaska, with Matty Richard and Kye Petersen. “We had two warm-up runs and then flew into this 1,200-foot spine wall with a massive cornice,” he says. “I knew I was going to go for it, but I was on one leg and I hadn’t skied in three weeks.”

Sayers goes last, airing 20 feet into his line and bearing 45 degrees towards his spine, but he’s high-sided along the way. He cartwheels 600 feet down the steep, rocky mountainside, over a bergschrund and mounds of rock. “I came to and looked up and saw all the pepper after stopping. I knew my knee was blown, but I thought, ‘Well God, thank you.’…. I shouldn’t have been there, but He didn’t kill me. It wasn’t my time.”

From Sayers’ journal: “Well that’s enough suffering for one man’s body! I know it’s not the first time I’ve stood in front of the mirror and told myself that I need to stop skiing.”

Baffin Island 2011

After a six-and-a-half-hour snowmobile ride to the base of what Sayers calls “the biggest, most enchanting couloirs on Earth,” he and his friends set up camp in –30C weather and build a perimeter alarm for polar bears.

On one of the first days of the three-week expedition, he says, “We did a 36-kilometre round tour to go ski a 3,600-foot couloir in the Stewart Valley, and I was swinging my feet almost right out of camp; they were frozen up right away,” he remembers. “We got out of the couloir and I was so afraid. I thought my feet were just completely done. I wanted to look at them, but I was like ‘Fuck it.’ I just had to keep going.”

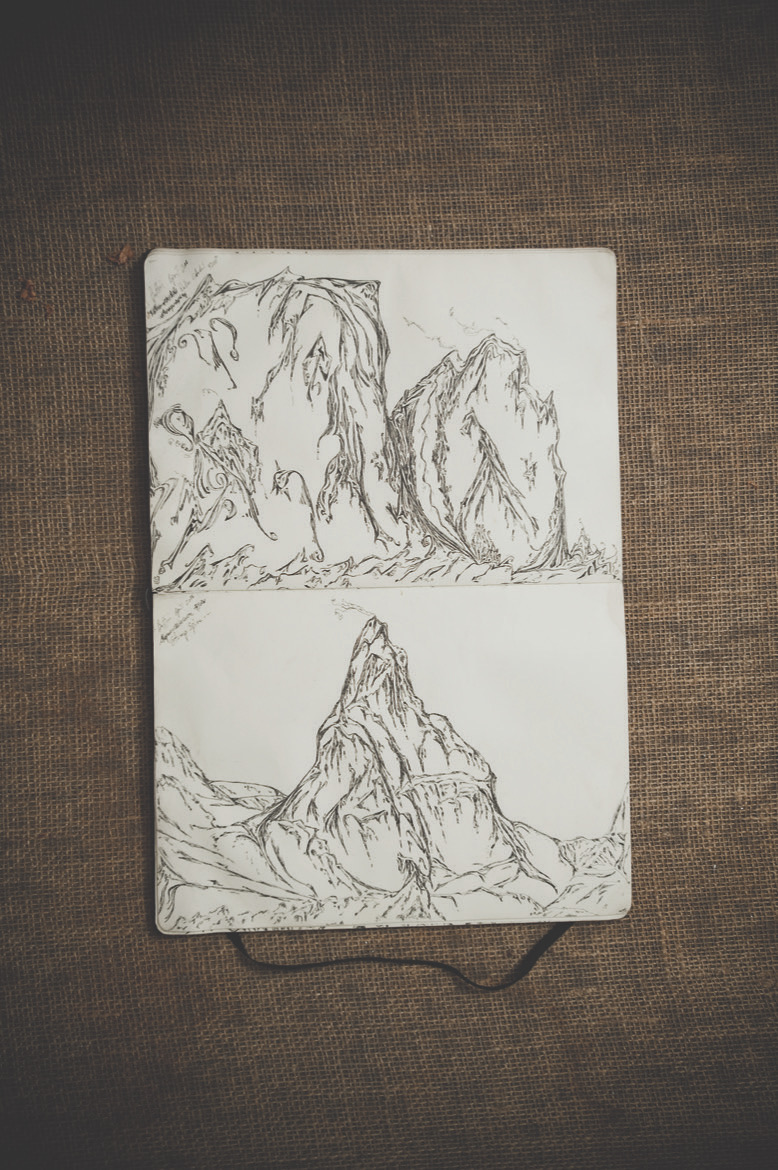

When they get back to camp, Sayers has two black toes. He spends the next five days by himself in a tent — in Arctic weather — trying to get his feet warm, drawing and listening for bears. On his lap the whole time is a shotgun.

From Sayers’ journal: “I must really make some changes in my life this year. I can’t keep going on each day with such pain in my body and spirit.”

La Grave 2012

After a bad heartbreak, Sayers sets out on a skiing binge with two friends and ends up in a remote couloir in a zone called Chateau Borel. As he feverishly skis the portion of the line that leads to a mandatory rappel, he starts to feel the snow degrade underfoot. On intuition, he stops 25 feet shy of the rappel to find he’s perched only inches away from blue ice — above 2,000 feet of exposure. It’s a situation not unlike the one that claimed the life of the legendary American mountaineer Doug Coombs in this same area.

Calling back to his partners not to approach, Sayers steps gingerly back uphill and they improvise an anchor off the chossy rock at hand. This calls for Sayers to hold a sling in place for his friends, and leaves nobody to do this for him. “You had to put the right amount of tension on it or it would kick off,” he says.

The sling holds, and he escapes unscathed, once again, but something inside him gives way. The next day he packs his things and leaves La Grave, where he’s lived for two winters, and goes to Morocco and Indonesia before eventually moving home to Whistler. “I had travelled too far and too long and seen too much and didn’t know how to put it in perspective.”

From Sayers’ journal: “In the past year I have surfed, climbed, biked, scuba-dived, meditated, loved, photographed, expeditioned in northern BC, Baffin Island, Kauai, Indonesia, Chile, Patagonia, Easter Island, Honduras, Costa Rica, Mexico, France, Japan, Romania, Bulgaria, Macedonia, Kosovo, Iceland and Dubai.”

Mentawai Islands 2014

After two years of emotional and physical recovery, Sayers takes a solo surfing trip to Indonesia and gets bit by the “wrong mosquito.” Soon after, he passes out convulsing. “I felt like I’d been hit by a truck,” he says. Dengue fever takes hold. The infection, sometimes deadly, leaves him hallucinating alone by a candle for the next week, but he embraces the visions. “I was just really blissful and grateful that I could experience another thing that might kill me but was giving me perspective,” he recalls. “In the end, I came out of it catching the best barrel of my life, and then it led into my best ski season ever.”

From Sayers’ journal: “I am thankful that I can clearly understand the purpose of my journey at this point in my life: to explore the far corners of this earth and to love and share inspiration with the people I connect with along the way.”

Matt Coté is a seni0r writer at Kootenay Mountain Culture Magazine. He admires the courage that faith lends to many of those who inspire him towards his own adventures.

Matt Coté

Matt is the associate editor at Forecast. He's been penning and editing ski, adventure and mountain culture-based stories for over a dozen publications for the last decade.

Related Stories

Everything Is Providence: Chad Sayers Checks In on the Rockies

Like an elfin, other worldly apparition in mid-summer's heat, Chad Sayers checks in on G3's new website with a…

Just an Ordinary Skier

No doubt a lot of the footage that will be featured in this film will come from the Kootenays. Seth Morrison loves his…

A Skier’s Journey – Iceland

"In Iceland's rough and remote Westfjords region, Chad Sayers, Forrest Coots, and Chad Manley step back in time to…

Wapiti Ready To (Indie) Rock This Weekend

Fernie's incredibly forward-thinking music fest is back for a fourth year. Check the lineup: Wil Greg Drummond…

Meet Hickshow Productions

Hickshow Productions is as grassroots as it gets: they're Slocan Valley sleddin' souls who have a scene or two to…

Meet Pemberton Carver Ryan Scoular

Third-generation carver Ryan Scoular of Pemberton, British Columbia, is a chip off the old block. By Lisa Richardson.…