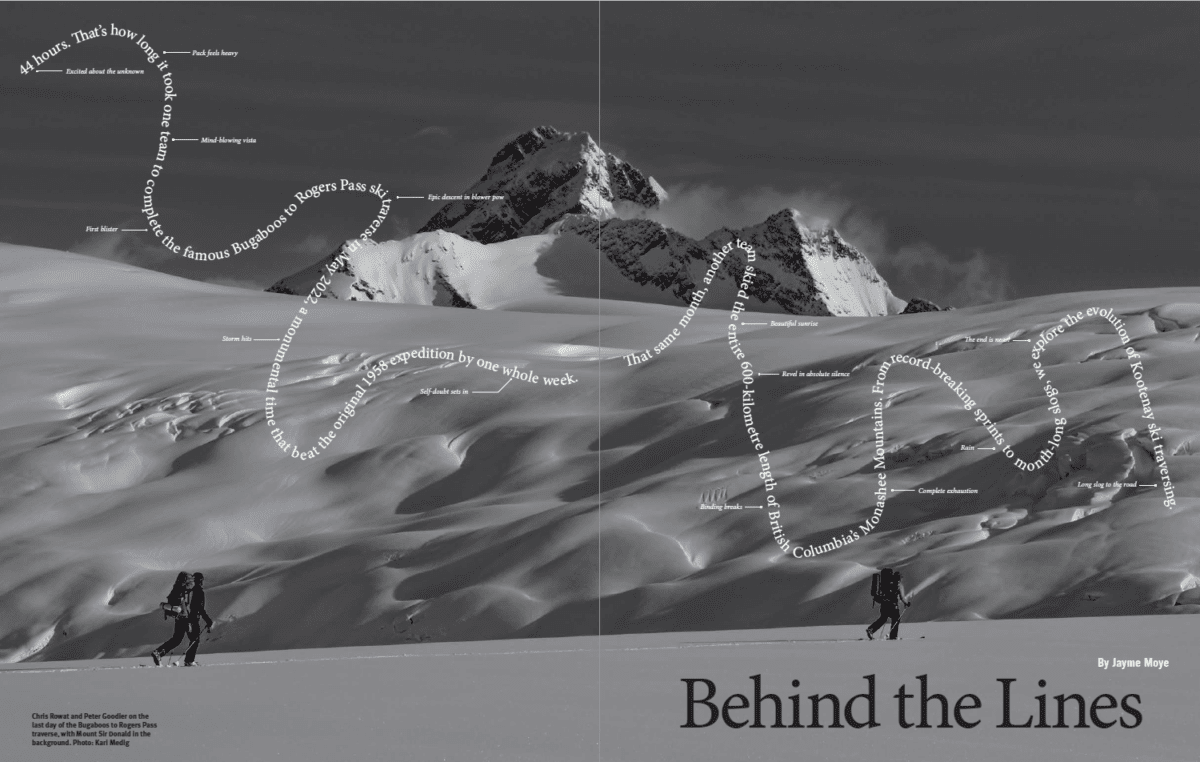

Forty-four hours. That’s how long it took one team to complete the famous Bugaboos to Rogers Pass ski traverse in May 2022, a monumental time that beat the original 1958 expedition by one whole week. That same month, another team skies the entire 600-kilometre length of British Columbia’s Monashee Mountains. From record-breaking sprints to month-long slogs, we explore the evolution of Kootenay ski traversing. By Jayme Moye.

Kylee Toth wasn’t hallucinating, exactly. More like misunderstanding what her senses were perceiving. Skinning up the pass at Mount Thorington, one of the highest peaks on her route at 2,653 metres (8,705 feet), Toth heard baby birds chirping, an impossibility at that altitude in May. And yet the sound persisted. Tweet, tweet, tweet, like a robin chick begging to be fed. That’s when she knew she was almost at her limit.

Toth, along with Emma Cook-Clarke and Taylor Sullivan, was 38 hours into the 130-kilometre-long (80-mile-long) Bugaboos to Rogers Pass traverse, one of eight grand traverses in the Columbia Mountains. A “grand traverse,” as defined by Chic Scott, author of Summits & Icefields: Alpine Ski Tours in the Canadian Rockies, is a wilderness route that follows a natural line through the crests of a mountain range, typically for 100 kilometres (62 miles) or more. Bugs to Rogers is the oldest and most iconic of the grand traverses, revered for its spectacular alpine scenery, steep slopes, heavily crevassed glaciers, and complex terrain. The route starts at the head of Bugaboo Creek before ascending Bugaboo Glacier, snaking across the peaks of the Purcell Mountains through Bugaboo Provincial Park and then into the Selkirk Mountains through Glacier National Park. The total elevation gain is 10,000 metres (32,808 feet), and most people take eight to ten days to complete the journey, carrying their food, avalanche safety gear, and camping equipment on their backs. Toth and her companions were attempting to do it in a single push, in less than 48 hours. While Toth’s style of traversing, called a speed traverse or a fastest known time (FKT) attempt, is relatively new, dreaming up epic ski journeys through the mountains of Western Canada is not.

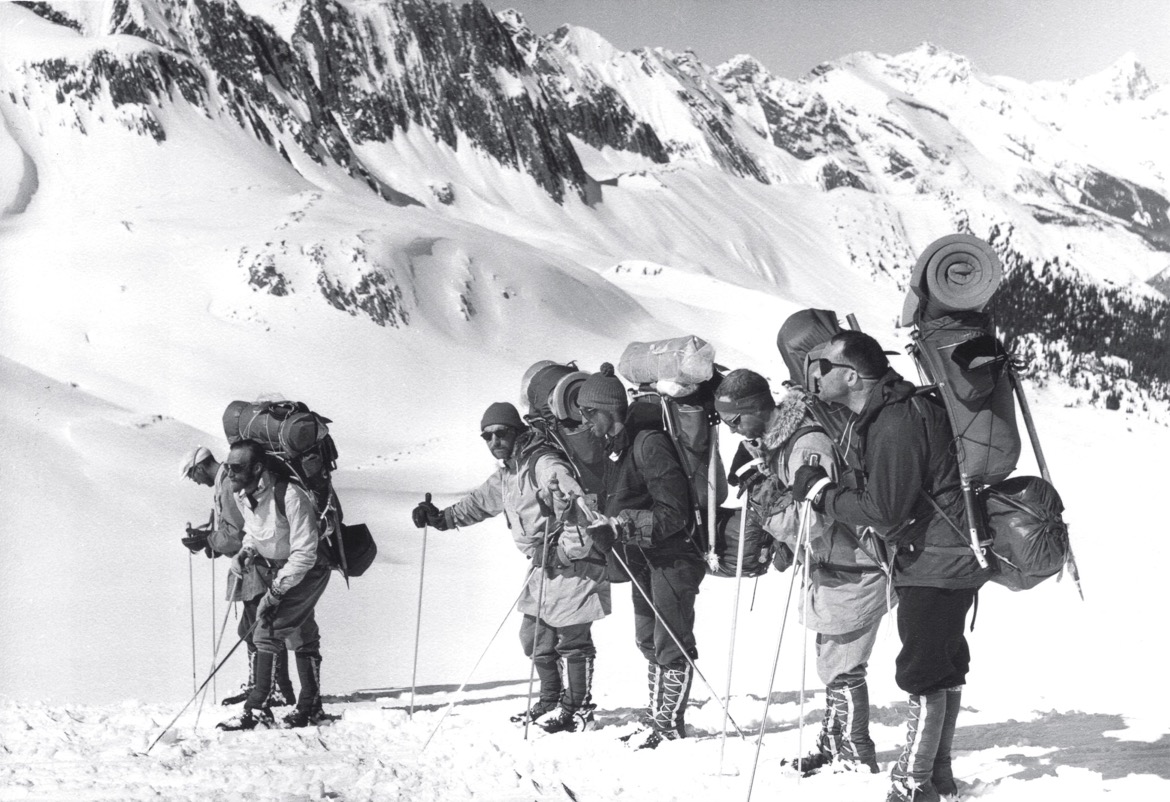

The Bugs to Rogers route was first completed in 1958 by four Americans from Dartmouth College. They did it over the course of nine days in June, combining skiing with bushwhack on foot. In 1973, Scott and three of his friends became the first to do the traverse entirely on skis. It took them 15 days because they had to hole up in a tent for five days and wait out a storm. Fast and light didn’t become a thing until the new millennium, after all the grand traverses—as well as dozens of shorter routes like the 45-kilometre (28-mile) Bonnington Traverse and the 40-kilometre (25-mile) Wapta Traverse—had already been established and oft-repeated. It was 2005 when climber and ski mountaineer Jon Walsh, with Douglas Sproul and Troy Jungen, set the first official speed record of the Bugs to Rogers route with a time of 80 hours.

When Toth attempted to set a new FKT for that route on May 1, 2022, the time to beat was 53.5 hours, established in 2021 by Greg Hill, Andrew McNab, and Adam Campbell. “What’s changed, even between the successive teams who’ve done Bugaboos to Rogers, is the gear has improved over time,” says Toth, “so our efficiency in movement has improved a lot.”

Toth is a former member of the Canadian national speed skating team and a current ski mountaineering (skimo) racer who competes in World Cup championships. She aspires to represent Canada at the 2026 Olympics, when skimo racing will make its debut. She says her pace on the Bugs to Rogers traverse was comfortable, a speed at which she could take in her surroundings. The real challenge was lack of sleep. The route was twice as long as all the ski traverses she’d done before, so when her sleep-deprived mind started playing tricks on her 38 hours in, Toth was grateful they were close to the finish. She and her team succeeded in their FKT attempt, completing the grand traverse in 44 hours and 37 minutes. An exhausted but elated Toth posted on Instagram, “I am stoked to help the next team that goes for it with any beta and planning advice I have as the teams before me so gratuitously did. I will share our adventure over the next few days on some posts, but for now I am still recovering and in awe of the adventure of a lifetime!”

A month later, speaking by phone from her home in Cochrane, Alberta, Toth reflects on what motivates her to do single-push ski traverses. “I think the Chic Scotts, their generation, had a lot of firsts that intrigued them, like the exploration of a route or a first descent. With our generation, a lot of stuff has already been skied, so I think it’s the same sort of adventurous spirit in us, but now our quest for adventure is leading us to these kind of serious link-ups and to ask how we can move efficiently through this terrain.”

Scott concurs, to a point. “I know that there’s something very nice in moving swiftly and efficiently in the mountains, and each generation has to do something new to make your mark,” he says, but he adds that the grand traverses shouldn’t be turned into a race. “I went to the mountains to get away from all that sort of bullshit.”

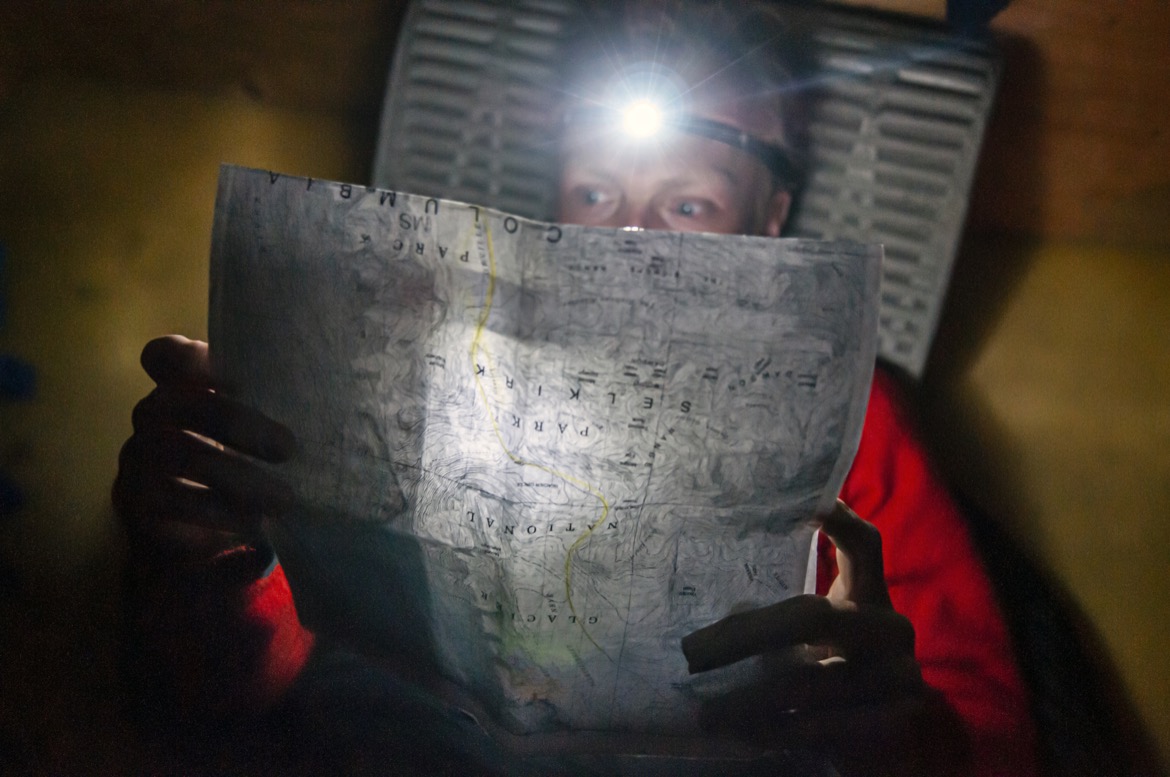

When he looks back on what he considers his grandest traverse, the Great Divide, which he pioneered with Don Gardner, Charlie Locke, and Neil Liske in May 1967, he recognizes that it was a drastically different era. Scott and his cohorts negotiated 320 kilometres (199 miles) of glaciated terrain and icefields on the Continental Divide from Jasper to Lake Louise wearing wooden skis and leather boots. The 1:50,000 topographical maps didn’t exist yet, let alone GPS. They used hand-drawn maps created in 1920 as part of a survey of the Alberta-British Columbia border. They also studied aerial photos of the area the Canadian government had commissioned after World War II. And they hand-placed their food caches by ski-touring into their intended route from various points on the highway. “We spent the whole winter planning it,” Scott says. The traverse itself took 21 days.

When Toth and I discuss Scott’s feat over the phone, she says, “The Great Divide traverse in the Rockies is one ripe for the shortening.” She goes on to say that Scott’s books are “awesome dream material” for those who want to do traverses in a different style, whether they’re interested in speed, like she is, or if they want to extend the overall length of the journey. The practice of linking existing traverses dates back to 1998, when Dan Clarke and Chris Gooliaff attempted to link all of the grand traverses through the Columbia Mountains, starting with the Northern Cariboos. The duo made it most of the way but failed because they were “unable to force a way through the Monashee range to link the Southern Cariboos with the Northern Selkirks,” Scott wrote in the 2005 book Powder Pioneers. Despite this, the 700 kilometres (435 miles) they did traverse over the course of 61 days set the stage for today’s modern explorers, most notably Douglas Noblet and Stephen Senecal from the Kootenays.

On May 7, 2022, Noblet, Senecal, and wildlife biologist Isobel Phoebus completed a 600-kilometre (373-mile) traverse of the entire Monashee Mountains range in British Columbia, from Grand Forks to Clemina Creek near Valemount, in 37 days. The Monashees were long considered the holy grail of the grand traverses, and it wasn’t until 2004 that Greg Hill, Aaron Chance, and Ian Bissonett completed the northern portion in 21 days. They bagged a whopping 21 peaks en route, which equates to about 30,000 vertical metres (98,425 feet), but they only travelled 210 kilometres (130 miles) between Revelstoke and Valemount. Noblet and his team’s version nearly tripled the distance and clocked in at 42,000 vertical metres (137,795 feet) of elevation gain. That’s the equivalent of 12 trips from Mount Everest’s base camp to its summit in just over a month.

Noblet and Senecal have also done full traverses of the Selkirks—520 kilometres (323 miles)—in 2016, as well as the Purcells—387 kilometres (240 miles)—in 2019. “The biggest draw for me is just getting to intimately know a mountain range,” says Noblet, who, when not skiing, works as a nature photographer, commercial pilot, and avalanche professional. He’s experienced firsthand in how the Monashee range is “much skinnier than the Purcells or Selkirks.” He knows where the creeks flow, where the valleys connect, and where the subranges are. And he has a better understanding of the scale of it all. “Walking the entire length of the parks, you see how their size compares,” says Noblet. “The Purcell [Wilderness] Conservancy is a big one. But there’s only one small park in the Monashees compared to the Selkirks and the Purcells.”

For Noblet, the biggest challenge of extending grand traverses is the logistics, figuring out the route and planting the food caches. He uses Google Earth and Google Maps to fine-tune what appears to be the natural line and to account for cliffs and otherwise inaccessible terrain, and he gets feedback from local guides. He also solicits friends and people who will already be flying into the area, like a pilot with CMH Heli-Skiing, to deliver the caches, which are placed at areas where he expects to be every four to seven days. Next up for Noblet and Senecal is extending two existing grand traverses to ski the full length of the Cariboos. “Every two to three years is pretty comfortable timing between big trips like these,” Noblet says.

Not everyone is looking to set an FKT or extend a grand traverse. For many, ski traverses are epic enough just the way they are. And although there is better tech and gear, adventurers are doing them pretty much the same way Scott and his pals did seven decades ago: slow and steady.

Leah Evans is a professional skier, Association of Canadian Mountain Guides (ACMG) hiking guide, and the director of a freeski camp for women called Girls Do Ski. She completed her first grand traverse in 2021 in the customary eight days. She did it with pro snowboarder Marie-France Roy and ACMG ski guide Madeleine Martin-Preney, and she chose the Bugs to Rogers route because it encompasses the peaks she sees from her home in Revelstoke. “The mountains themselves were my major inspiration,” she says. “I wanted to travel through them, to be immersed in them.”

As a woman who has devoted her career to skiing downhill, Evans also saw completing the Bugs to Rogers traverse as a ski-touring rite of passage, a logical progression of the skills, experience, and education she’s amassed since moving to Revelstoke from Rossland in 2010. Looking back on the journey, which was the subject of the documentary film Mind Over Mountain (2021), Evans was very much out of her comfort zone physically. “I was used to doing maybe one big day like that with time to recoup and a warm place to make food,” she says. “But this was like, you’re maxing out your tank and then you’re having to do more stuff [like set up camp]. It was an eye-opening experience. I gained big-scale respect for the mountains.” Is Evans planning on doing any more grand traverses? “I’m good,” she says. For most of us, once in a lifetime is more than enough.

While award-winning adventure journalist Jayme Moye enjoys ski touring, she prefers to embark on grand traverses vicariously through her story subjects.

Jayme Moye

Jayme Moye is an award-winning writer who specializes in stories about travel, mountain sports and culture, and pushing the limits of human potential. Her freelance work regularly appears in Outside, Canadian Geographic, National Geographic, and Condé Nast Traveler, among others. She is a Senior Writer with Kootenay Mountain Culture Magazine.

Related Stories

Ski Your Ass Off

Winter is upon us. But as we look to the future, it's not a bad idea to drift back into the past. The glorious, super…

History of Ski Aerial Acrobatics

One of the most influential ski films of all time. Dick Barrymores documents what started freestyle skiing. From 1969…

Powder Highway Ski Bum at SWS

Chris Tatsuno has done an amazing job chronicling his Ultimate Ski Bum Powder Highway winnings. In this episode he…

Powder Highway Ultimate Ski Bum Contest

We had to post this simply because it features KMC Editor, Mitchell Scott, in his formal acting debut. The contest is…

Powder Highway Ultimate Ski Bum Vlog

We've been getting lots of requests from KMC readers as to the whereabouts and current activities of the Powder Highway…

Tide Lines Premiere

On September 24th, the Vancouver Festival of Ocean Films and the Vancouver Aquarium are very pleased to present the…