In 1956, the Sinixt people were declared extinct by the Canadian government. After an 11-year legal battle, the Supreme Court of Canada has ruled the Sinixt should now have access to their traditional hunting territory, which encompasses a large swath of the West Kootenay region. What does this mean for their “extinct” status and their future? By Bob Keating

Editor’s Note: This story first appeared in our winter 2021/22 issue of Kootenay Mountain Culture Magazine and we received some feedback asking why we didn’t interview Sinixt members currently residing in Canada. This story is specifically about the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation in Washington and its decade-long legal battle. It’s a significant piece of a much larger overarching Sinixt story that will have ramifications for all First Nations with traditional territories that straddle the Canadian-American border.

SHELLY BOYD MAKES ME huckleberry pancakes at her home in Inchelium in northern Washington. We’re supposed to be out paddling her sturgeon-nosed canoe on a little lake nearby, but a late-spring snowfall has descended, so we settle for breakfast and conversation in her bright home in the forest, her wood stove crackling as we talk. Boyd is my guide here in this small community of homes and Indigenous businesses just across the border from Grand Forks, British Columbia, on the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation. She tells me about being a Sinixt facilitator, a liaison of sorts between outsiders like me and the reservation, and how her husband was the first to hold the position before his passing in 2016. It’s a job that takes her into Canada a lot, and she expects even more trips in the future. “There’s never been a time since I’ve been around that is so crucial for my people,” she says.

The Sinixt argued they were driven out of Canada to the Colville Reservation by early settlers and governments. Now they want to return home, and, after an 11-year legal battle, a Supreme Court of Canada decision last April gave them the right to do so. It’s up to Boyd and her people to figure out what to do next. The Sinixt are understandably suspicious of Canadians, but as a former CBC Radio journalist, I’ve been covering their story for so long they welcome me, although not before one of their historians checked out my past. Boyd says they want their story told from the beginning. And they’ve allowed me to do it.

of rocking chairs for the past few days.”

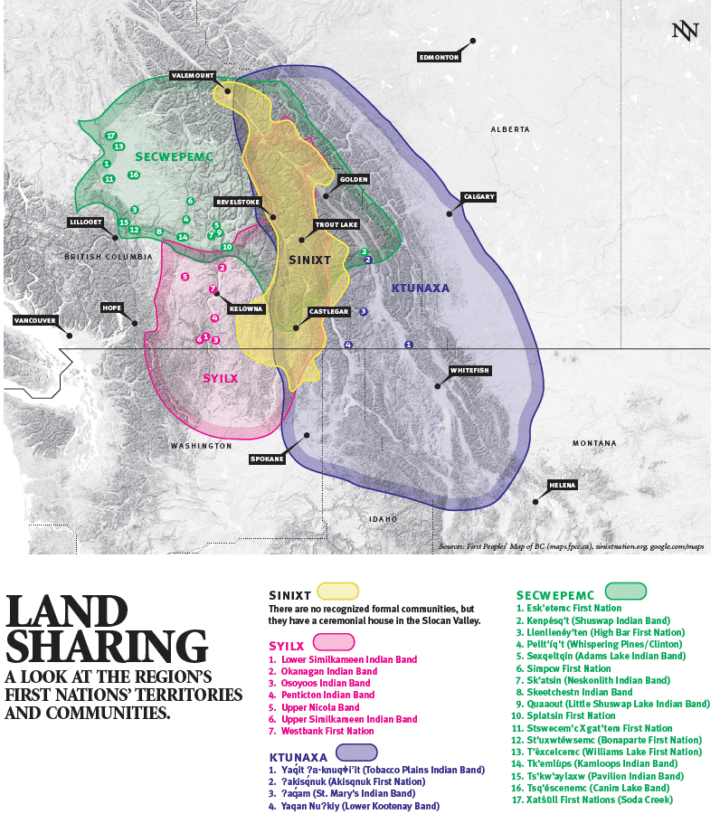

BY THE TIME the Sinixt saw their first white man, explorer David Thompson in 1811, about three-quarters of them had been wiped out. It was near Revelstoke they encountered him, and he noted the pockmarked faces of survivors, a telltale sign that smallpox had preceded his arrival via infected natives from neighbouring tribes and on their trade goods such as the infamous Hudson’s Bay blankets. The Sinixt weren’t a large nation to begin with — according to oral history, pre-contact numbers were estimated to have been between 2,500 and 3,500 — but their traditional territory was vast. About 80 per cent was located in present-day Canada and followed the Columbia River north from Kettle Falls, Washington, for over 200 kilometres. It was the river that served as their main travelling route and primary source of food. Salmon made up most of their diet, but the Sinixt were also remarkable hunters. They ingeniously trained dogs to herd deer to the waters’ edge, where they pierced them with arrows from canoes.

By the late 19th century, the Sinixt, already weakened by smallpox and influenza, were forced to contend with an influx of miners, settlers, and Russian immigrants known as Doukhobors, who pushed them off the best land left in the Kootenays. The latter group would publicly apologize for their behaviour decades later, but the damage had been done. Sinixt numbers dwindled. In 1956, when the last remaining Sinixt person in British Columbia, Annie Joseph, died in a Vernon hospital, the Canadian government took the rare step of striking the Sinixt from the Indian Act, declaring them extinct as a people. Seven years later, the British Columbia government began damming up the Columbia River.

Of course, the Sinixt were never extinct. Over the last century, surviving members drifted south to the Colville Reservation, which was created by the United States government in 1872 to corral 12 different American tribes, some of which were traditional enemies. Initially, the reservation was one of the biggest in the country and it was bountiful, with epic salmon runs on the Columbia and its tributaries, but various acts of Congress significantly shrank its size. Then, in the 1930s, the federal government started constructing dams on the river. The salmon runs ceased.

The Colville Reservation soon became one of the poorest zip codes in America. By then, the Sinixt had moved south again, this time to a tiny settlement they called Inchelium. It’s still on the reservation but completely outside of their traditional territory. “It’s a hurt many of our elders didn’t even speak about,” Boyd tells me.

Despite the poverty and oppression, the Sinixt refused to accept their own extinction. Their numbers grew in Inchelium, and they were often elected to lead the 12 tribes on the reservation. New generations heard stories of ancestral land in Canada, and some snuck in to hunt or get a look at the place. Others dreamed of returning.

In 1989, the Sinixt began to assert a form of sovereignty in Canada. That was the year Sinixt bones were unearthed by a road-building crew in British Columbia’s Slocan Valley. When word drifted down to Inchelium the remains were destined for a museum in Victoria, people mobilized. Members were sent north to build an encampment, and they refused to leave Canada without the bones of their ancestors. “The elders asked me to coordinate the blockade,” says Yvonne Swan, who worked at the tribal office and helped lead the protest. “The elders ask you to do something for your people, you can’t say no.” Swan and the others camped in the community of Vallican for many months until the provincial government finally relented. That victory set a precedent and would help spur other protests, such as the famous stand-off in Oka, Quebec, in 1990.

Although the burial ground in Vallican was named a historic archaeological site and the highway was diverted around it, the Sinixt were no closer to recognition in Canada as a people. The Colville Confederated Tribes leadership decided to do something bold: break the law. In the fall of 2009, they sent conservation officer and Sinixt hunter Rick Desautel into British Columbia to shoot an elk. Nothing about the hunt was legal. Desautel is American and doesn’t have a British Columbia hunting license, but his intention was to force the province’s hand. “I went out to pick a fight,” says Desautel. “And sure enough, I got my elk.” Desautel phoned local conservation officers hoping to be arrested, but they were initially unwilling to engage. He returned the following October and repeated the hunt. He bagged another elk; this time, he was charged with hunting as a non-resident and hunting without a license.

It’s a good thing Desautel and the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation are patient because his case crawled through the court system for over a decade. Based on overwhelming physical evidence of Sinixt pit houses and grave sites, combined with the testimony of elders and historians, the initial trial judge ruled sections of the Wildlife Act do not apply to Desautel or the Sinixt because they are the legitimate First Nation in the West Kootenay and have constitutional rights to hunt in their traditional territory. Desautel won that first case, but the province appealed. He went on to win at every level of British Columbia court, including provincial court, Supreme Court, and the Court of Appeal, but the province insisted on taking the matter all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada.

On April 23, 2021, Canada’s most powerful court ruled in favour of the Sinixt, saying they have a “constitutionally protected Indigenous right to hunt in ancestral territory north of the border.” It was a historic moment for border nations across the continent, but especially for the Sinixt, who can once again access the land of their ancestors. “We’re not going back to the museum and standing next to the dinosaurs,” Desautel told me with a chuckle when he heard the news. He had gathered with other members of the Sinixt tribe at Kettle Falls to celebrate their existence. “I just want to be able to hunt like my ancestors did.”

THE SUPREME COURT of Canada affirmed what Boyd never doubted: the Sinixt are a people. The West Kootenay is their home, and they did not leave it willingly. The obvious question now is, what does it mean? These are uncharted waters. The Sinixt have returned to pre-contact numbers at about 3,500 strong on the Colville Reservation alone. Though they consider themselves Sinixt first, they are also Americans who, at the very least, now have hunting rights in a West Kootenay valley that generates billions of dollars in hydroelectric power from dams built right after they were declared extinct.

Mark Underhill, the lawyer for the Sinixt, always considered the toughest part of the case to be convincing the court the injustice of what happened to the Sinixt outweighs the fact they are American citizens. “For them, what is on the line is not just their legal rights but their very identity,” he says. Underhill and others are now trying to determine what this new status means, but one of the first steps will be education. A band office has been established in the Slocan Valley, and its staff will play a pivotal role in rebuilding, as will Boyd. She helped produce the recent documentary Older than the Crown about the history of the Sinixt people, and she also teaches her tribe’s language and culture to students at various learning institutions.

In fact, Boyd says she often finds herself in the strange position of introducing herself to West Kootenay residents whose forefathers forced her people out. It’s customary in this region that city councils, school boards, and other public bodies start meetings by thanking the Ktunaxa, Syilx, and Secwepemc nations, which also claim the West Kootenay as their traditional territory. Recently, the school board in Nakusp decided to say it’s located in Sinixt territory. It’s a start.

One of the first documentaries Bob Keating did for CBC Radio in the Kootenays was the story of the Sinixt people and their fight to prove they exist. It also happened to be the very last story he told for the CBC some 20 years later, before he retired in May 2021.

Bob Keating

Bob Keating worked for the CBC for three decades in Alberta and British Columbia. When he’s not out looking for muck to rake, Keating is a music geek and outdoor lover who, like a lot of Kootenay residents, jumps off the bike in the fall onto a pair of skis.

Related Stories

Sternwheelers of Kootenay Lake

Our Art Director loves his history. He recently found this very comprehensive site exploring the sternwheelers of…

Kootenay Coldsmoke Yeehaw!

Another year of Kootenay Coldsmoke Powder Fest good times goes down in the history books. As the MC for the Powderkeg…

Toy Story 3 – The Kootenay Connection

What do Toy Story 3, the iPad, and KMC contributing photographer and part-time kootenay resident Bryce Duffy all have…

Kootenay Sufferfest

What tastes so good in there? We are stoked to announce that Kaslo Sufferfest kicks off this weekend, with record…

Merry Christmas People

We here at Kootenay Mountain Culture Magazine would like to put out a big giant snow filled hug to everyone who's been…

Kootenay Spirit Festival

It's time to get in touch with your spiritual side, Kootenays. Buy tickets to the Kootenay Spirit Festival now.