Compiled as part homage to a friend and conservation pioneer, a new book showcases the mysterious American desert canyons discovered by legendary East Kootenay photographer Pat Morrow and his fellow dirtbag disciples. Story by Jeff Pew.

“We were mesmerized by the crazy architecture of the canyons,” Pat Morrow says from his house in Wilmer, British Columbia, perched above the East Kootenay Columbia Wetlands. “It was a place that warmed the psyche: the ochre, the yellow hues, the heat hidden within the earth. It was a way for us to escape our endless Canadian winter and revel in the desert.”

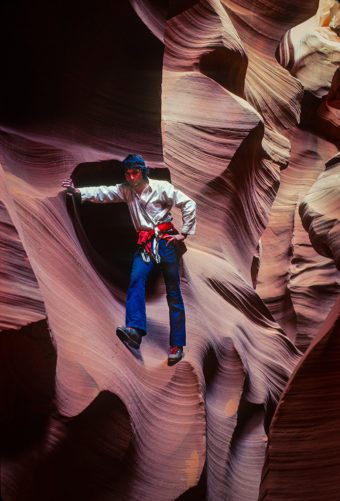

Morrow, 66, is talking about the decade, beginning in 1975, when he and friends Art Twomey and Jeremy Schmidt discovered and photographed some of Arizona’s most remote and intricately carved slot canyons. Now, 43 years later, these images appear in the beautifully designed book Searching for Tao Canyon, named after their Taoist ideal of a slot canyon—more an elusive archetype than an actual place. “We’d spend weeks, stretching into months, living in the canyons,” says Morrow, who was inducted into the Order of Canada in 1987 for his mountaineering exploits. “We were dirtbags who thrived on rice and beans. Those were the days of expensive Kodachrome slide film. We’d sit for hours observing the way light moved through canyons before we took our first shot. As climbers, it was natural to push the envelope, to go to places cameras hadn’t. In the deepest canyons, we were suspended hundreds of metres below the surface, hanging on rat-chewed ropes, and using jerry-rigged tripods.”

Morrow sits cross-legged in his living-room chair surrounded by keepsakes from climbing expeditions: a statue of the Buddha, a prayer wheel, a wall print of Tibetan pilgrims. He reflects on his friendship with Twomey, who died in 1997 in a helicopter crash in his beloved Purcell Mountains.

Morrow was a 17-year-old kid in Kimberley, British Columbia, when, in 1969, he met 25-year-old Twomey, who’d recently dodged the US Vietnam War draft to build a trapline cabin in the remote Purcells.

Compared to my peers at the time, Art was pretty exotic,” Morrow says. “He was a glacial geologist, photographer, storyteller, mountain climber, and guitar strummer. Art’s frugal lifestyle opened my eyes to the rich possibilities of being independently poor. I realized I could live a high-quality life by keeping my overhead low.”

One of Morrow and Twomey’s early trips into the Leaning Towers group of peaks led Twomey to spearhead its preservation within the Purcell Wilderness Conservancy Park, southern Canada’s largest protected wilderness area. “Art brought the conservation ethic to the Kootenays” Morrow says. “He reminded us how lucky we were to live in this paradise.”

In 1970, while exploring northern Arizona with a friend, Twomey accidentally discovered the hidden world of slot canyons. Five years later, Morrow and Schmidt, Twomey’s friend from college, would follow him into this mysterious landscape. Schmidt, who now resides in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, is an author and consultant for National Geographic Expeditions. He narrates the book and describes their first encounter with slot canyons, “Just when you think you know where you’re going, and how to get there, you find you don’t know much at all … as if enjoying its big joke, the desert opened in a jack-o’-lantern grin. They came upon it suddenly—a ragged crevasse in glaring bedrock, a dark slash directly across their path of travel.”

Years later, one of Twomey’s slot-canyon photos appeared on the cover of the 1974 Sierra Club Wilderness Calendar. Suddenly, the world was clamouring to know more about this mysterious landscape sculpted in the earth. “We knew we had a project the world needed to see, but it had to be done through a certain filter,” Morrow says. “Our aim was to sensitize readers to go easy on these fragile places if they chose to search them out on their own. That’s why we always used pseudonyms when naming canyons, as seen in the title of the book.”

By the early 80s, the trio’s careers were taking off, and their adventures led them to other, separate destinations. They sold unidentified slot-canyon photographs to magazines worldwide, but always envisioned a larger collection such as Searching for Tao Canyon. “Hopefully, this book can help earn support in defence of large tracts of the American desert that have come under threat by the current administration,” Morrow says.

They dedicate the book as a legacy to their friend Art Twomey. “If it weren’t for visionaries like Art,” Morrow says, “our world would be in a lot worse shape.”

Jeff Pew

Jeff Pew is co-founder of Poetry on the Rocks, an annual celebration of spoken word in the East Kootenays. He works as a creative writing teacher and counsellor to teens. He lives in Kimberley, BC.

Related Stories

Here Are The Secrets of Spring in Whitefish, Montana (Hint: There Are Fewer Visitors)

Spring is an excellent time to visit Whitefish, Montana, because the trails are loamy, the wildlife is roaming, and the…