Rogers Pass is maintained by the military and a vital national transportation corridor so it’s no surprise the world-class touring playground has been closed to backcountry adventurers before. And parts are now off limits again, temporarily. In this story that appeared in the latest Kootenay Mountain Culture, writer Matt Coté learns how Parks Canada is trying to manage the winter masses.

March 7 update: It’s happened. Parts of Rogers Pass are now closed because of poaching. All of Avalanche Mountain and NRC Gullies are off-limits because ski tracks were found on the MacDonald West Shoulder, an area that’s permanently closed in the winter months. Shelley Bird at Parks Canada says, “They are closed at least until we receive significant snowfall to cover tracks into the prohibited area. Then Parks Canada will decide whether or not to reopen it this season. It is currently still a temporary closure.” Here’s Matt’s story:

March 7 update: It’s happened. Parts of Rogers Pass are now closed because of poaching. All of Avalanche Mountain and NRC Gullies are off-limits because ski tracks were found on the MacDonald West Shoulder, an area that’s permanently closed in the winter months. Shelley Bird at Parks Canada says, “They are closed at least until we receive significant snowfall to cover tracks into the prohibited area. Then Parks Canada will decide whether or not to reopen it this season. It is currently still a temporary closure.” Here’s Matt’s story:

Rogers Pass sprawls out in rainforests draped off granite peaks that have erupted through primeval folds of ice, and it gets more snow than almost anywhere in Canada—up to 17 metres a winter. For backcountry skiers, it’s a Mecca. But it is planted in the middle of Glacier National Park, where it shares a right of way with a national highway and railroad, and it’s not just the glaciated terrain that’s hard to navigate—so is the local Winter Permit System that Parks Canada and the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) operate to avoid conflicts between the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), skiers, and avalanche control. While few people remember it was once illegal to ski in Rogers Pass, locals fear a new surge in frothy snow seekers could inadvertently make it illegal again. With upward of 30,000 skiers visiting in recent seasons, Parks Canada has taken note. It has just launched an online app to help make newcomers aware of the rules of the permitting system, and to improve the flow of information to all skiers.

Major Albert Bowman Rogers took a full year to find his famous pass through the peaks sandwiched between Golden and Revelstoke in British Columbia. He found it in 1882 and the CPR laid rails through it in 1884, which brought Swiss guides. Glacier National Park was established in 1886, and Rogers Pass became the birthplace of North American mountaineering.

The Trans-Canada Highway followed in 1961, making the creviced throughway—threatened by over 140 avalanche paths—the most precarious-yet-vital artery in Canadian transcontinental ground transportation. Since then, Glacier National Park and the CAF have run the world’s largest mobile artillery avalanche control program. Between 1961 and 1995 it was actually illegal to ski in most of Rogers Pass because authorities didn’t want someone to get hit by projectile explosives used to trigger controlled avalanches.

Today, skiers are able to access the terrain above the highway thanks to a rotating Winter Permit System of 13 zones developed by Parks Canada to follow the military’s shooting schedule. The trouble is, permitted skier visits have almost doubled in the past four years, and it’s challenging to share all the rules and why they’re necessary. Take last winter, for instance, when an online fracas broke out in Revelstoke after locals learned of multiple skiers on MacDonald West Shoulder, an area in the park that’s permanently closed in winter. On social media, some feared highly publicized incidents like these could end public access.

Thankfully, those at the top know the system is confusing. That’s why Parks Canada launched a mobile-friendly web-based app that explains daily openings. It’s also placing open and closed singage with lighting in the parking lots and installing a new interactive map in the Rogers Pass Discovery Centre. “It’s probably the most complex place to ski in North America,” explains Shelley Bird, Parks Canada’s communications officer. “We want to catch some of those people who are totally unaware of the permit system.” For example, all visitors need a national park Discovery Pass as well as a daily or annual permit, and if you want to overnight, that’s another piece of paper. Plus it’s imperative to know what terrain is closed. Because fragments from explosives could hit a skier up to a kilometre away, it’s a violation of the National Parks Act to ski where you shouldn’t—to the tune of up to a $25,000 fine. So, while the bureaucracy seems over the top to newcomers, seasoned locals get it.

“I don’t think more people are breaking the rules, it’s really a small fraction of the visitors. I just think it’s more high profile now with the internet,” says Douglas Sproul, author of the guidebook Rogers Pass: Uptracks, Bootpacks & Bushwhacks. “What we should be concerned about is the military. They’re black and white, dude, no middle ground. I fear one day some high brass will catch wind of this and shut it down.… If we want to ski there we just have to learn it. It is a bit complex. But you know what would really suck? Getting blown up by a howitzer! I’ve been really close, man, it’s no fun. And, yes, I do fear losing access again. Take a look at a map and imagine all of the terrain facing the highway closed.”

“What we should be concerned about is the military. They’re black and white, dude, no middle ground. I fear one day some high brass will catch wind of this and shut it down.” – Douglas Sproul

Long-time devotees like Sproul still remember an incident 10 years ago when the CPR cut off coveted classics like the Tupper Traverse, Mount Smart, and Flat Creek because a single skier inadvertently blocked a train on a precarious stretch of tracks. The CPR—which is grandfathered into its right of way—shut down access to all skiers as a result, proving the transportation corridor takes precedence. It took Parks Canada three years to reroute affected access trails far enough away from the tracks to satisfy the CPR and reopen the cherished areas.

“We’re on your side,” Bird says, citing that a big part of Parks Canada’s mission is to preserve the enjoyment of these national sites for all Canadians. And while her team is working hard through direct measures and education campaigns to make the rules clearer, there are still occasions when we have to step up and pay closer attention. They are the mountains, after all, so savviness is always a prerequisite.

Related Stories

91 Octane – $10,000 Season Pass

"With a 125 years of skiing experience 91 octane presented by Shreddy Times release their teaser $10,000 season pass.…

Win a Season’s Pass to Red Mountain Resort

Red Mountain Resort in Rossland, BC, is one of our favourite places to shred. And it's that much better when you win a…

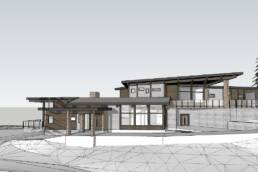

Eagle Pass Heliski’s New Lodge to Open January

Eagle Pass Heliski has announced its new 9,500-square-foot lodge, located in the Monashee Mountains, will be…

Earl Grey Pass Trail Gets A Facelift

One of the Purcell Mountains' most gruelling and historically significant multi-day hiking routes gets some love. By…