KMC 41 – The 180 Issue

It's not about going back the way we came. It's about looking at something from every angle—spinning it, flipping it, turning it inside out—then leaping forward into the unknown.

As Kootenay Mountain Culture enters its third decade of publication, we shift our focus with this particular issue to help see things from another angle. We celebrate the work of government employees who are busy behind the scenes creating some of our most popular play places. We rethink where our food comes from and consider how to honour death differently. You might not agree with every viewpoint you encounter in this magazine, but understanding another perspective is a form of moving ahead, and that is a beautiful trick indeed.

Kootenay Man To Search For Gold With His Hand-Built Submarine

An East Kootenay man will hunt for a fabled gold boulder in the deep waters of British Columbia's Kootenay Lake — using a submarine he built himself. By Vince Hempsall

On April 23, 1894, an article ran in the Nelson Tribune newspaper about a boulder of gold Randal Kemp discovered near Crawford Bay, on the shores of Kootenay Lake. Kemp said it measured 68 x 35 x 30 centimetres, about the size of a microwave, and estimated it was 1,300 kilograms. Its size was never proven because while Kemp was lowering it down a slope onto a boat, his rope snapped. The boulder sank to the bottom of the 400-foot-deep lake. The story could have been a hoax made up by Kemp, but that hasn’t stopped scuba divers from attempting to find the boulder in recent decades. None have been successful. But this spring, a Fairmont Hot Springs, British Columbia, man is hoping to locate it with the help of his homemade submarine.

https://youtu.be/7OTvuiXL1LY

Hank Pronk started building submersibles as a hobby when he was 16, and now, at the age of 59, he’s created his eighth one. He called it the Elementary 3000 because, he says, “It’s the world’s deepest-diving homemade submarine that’s pressure-tested to 3,000 feet.” The rating comes from a test done at a pressure chamber in Vancouver, but the deepest his submarine has physically travelled is 1,000 feet in the West Kootenay’s Slocan Lake last year. Pronk built the all-electric steel sub to American Bureau of Shipping standards, and it features a robotic arm, dome window, camera, buoyancy tanks, backup air supplies, and thrusters that operate off two golf-cart batteries. The craft is 3.3 × 1.8 metres, weighs 1,360 kilograms, and the interior is big enough to fit Pronk’s six-foot frame comfortably when he’s seated in a cross-legged, upright position. He says he can explore about 1.6 kilometres underwater on one battery charge, and aside from hunting for gold this spring, he’s also planning to shoot footage of the wreck of the SS City of Ainsworth paddlewheeler, which sank in 1898 near Kaslo, British Columbia, and look for a fabled boxcar of silver ingots on the east side of Kootenay Lake.

https://youtu.be/EGl8hC1Pd7Y

As for how he transports the submarine, Pronk owns a house-moving company and says he’s used to winching and transporting large objects. For the engineering aspects of building submarines, though, he learned almost everything either online or in books. And how much did the Elementary 3000 cost him to build? “If I told you, you might tell your wife, and then she might tell my wife,” he says, “and then I’d be in trouble.” Unless, of course, he finds that gold boulder.

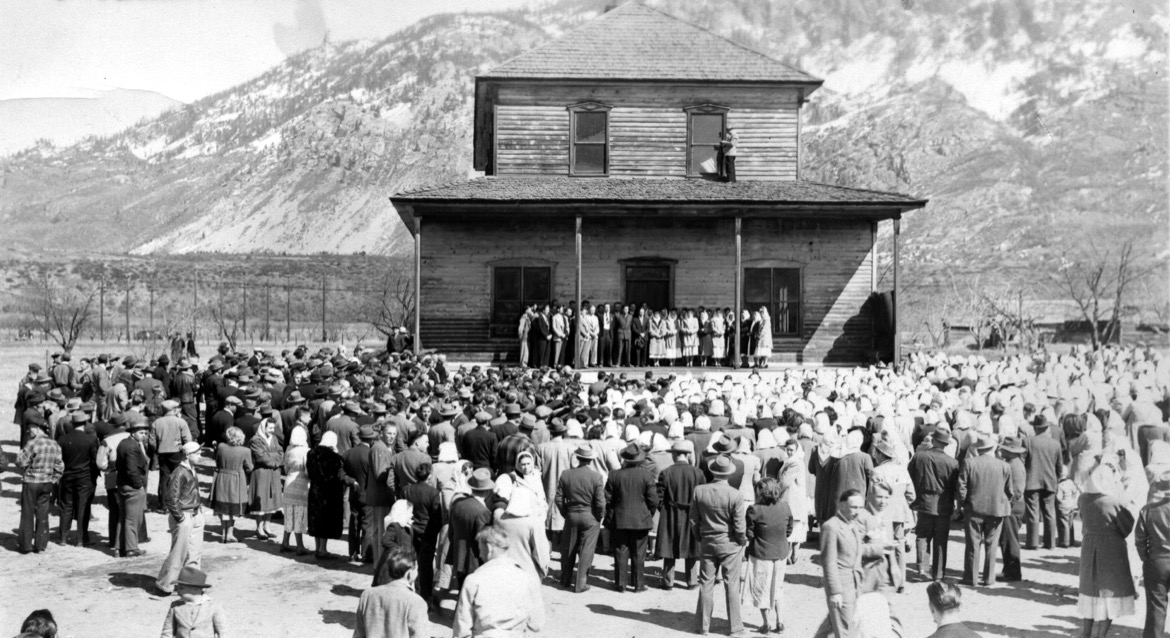

Gallery of Gruel – The First Winter Traverse of the Purcells

Three years after an epic grunt along the length of the Selkirks, four British Columbia ski mountaineers lay claim to an equally arduous first-ever ski traverse of the neighbouring Purcells. Would they undertake the beautiful voyage again? Yaaa–probably not. Story and photographs by Douglas Noblet.

Photographer Douglas Noblet likes to suffer. In 2016, the Nelson, British Columbia, native helped organize a team to ski traverse the Selkirk Mountains, from Kootenay Pass to the Mica Dam, north of Revelstoke, British Columbia. During that 36-day, 520-kilometre (323-mile) trip, they endured unseasonably low snowpack, two broken skis, two broken bindings, three broken poles, and a wily pine marten that stole two kilograms of food. (You can read about that adventure in KMC Winter 2016/17.)

Despite the challenges of that trip, he and a core crew of four others decided to do another British Columbia traverse in April 2019, travelling from Creston to Golden, likely the first continuous ski trip along the entire length of the Purcell Mountain range. The team didn’t suffer any broken gear, and the snowpack was better than their mission three years earlier,

but given that it was April, spring hazards were high and they regularly triggered avalanches up to size 2.5. Thankfully, no one was hurt.

In all, the Purcells journey spanned 380 kilometres (236 miles) over 26 days and included 31,000 metres of vertical. “People often ask me if I would do the trip again, and the answer is an easy, no!” says Noblet. “But on the walk down Quarts Creek, myself and Steve [fellow Nelsonite Stephen Senecal] found ourselves talking about the Monashee traverse. Give us a season or two off and you might just see us attempting the next mountain range.”

Shambhala Announces its 2022 Line-up

Shambhala, Canada’s longest-running electronic music festival, released its 2022 lineup today after a two-year hiatus.

Featuring a more diverse lineup than ever seen before, the Shambhala 2022 roster was released today and it stacks world-class headliners alongside Shambhala favourites and up-and-comers. The festival will run from July 22-25, 2022 at its permanent location on the Salmo River Ranch in Salmo, British Columbia.

The line-up includes Amon Tobin Presenting Two Fingers, BBNO$, Chali 2na & Cut Chemist, Channel Tres, Chris Lake, Chris Lorenzo, CloZee, Cordae, DJ Jazzy Jeff, DJ Premier, Greg Wilson, Justin Martin, Mr. Carmack, Rudimental (DJ Set), Sébastien Léger Modular Live, Slander, Subtronics, TOKiMONSTA, Valentino Khan, and What So Not. There will also be a mystery Tier 1 'Surprise Set’ which has yet to be announced.

This will be the first time in two years Shambhala will take place as it was on hiatus due to the Covid-19 pandemic and public health restrictions. “To say we are thrilled to be back is an understatement," says Shambhala Music Festival founder Jimmy Bundschuh. "To a lot of us, Shambhala is way more than just a festival. It’s a place where we come back to connect with old friends and make new memories, and to have been starved of that over the last two years has been tough. But we’ve taken that time to rediscover who we are both musically and community-wise, and this year's diverse lineup reflects that."

https://youtu.be/Y67S-ZWKRT4

In addition to today’s lineup release, there will be an additional 100+ performers that will be announced as the Living Room, the Grove, the Fractal Forest, the AMP, the Village and the Pagoda each release their own respective lineups. Guests can also expect a complete redesign of the Village Stage.

Tickets for the 23rd Annual Shambhala Music Festival are already 90 percent sold out. Early bird tickets are completely gone and general admission tickets are listed at Cdn$525. For more information, visit shambhalamusicfestival.com.

Here Are The Secrets of Spring in Whitefish, Montana (Hint: There Are Fewer Visitors)

Spring is an excellent time to visit Whitefish, Montana, because the trails are loamy, the wildlife is roaming, and the visitors are few and far between.

The world has discovered Whitefish, Montana during the summer season, and for good reason: the waters are warmer, the alpine flowers are blooming, and the beaches and bike trails are bathed in sunshine. For those who prefer a less busy holiday though, spring is the perfect time to visit Whitefish because the sun's still shining and the trails are buff but there aren't any line-ups at the many bars and eateries in town. If you are someone who desires to protect places for future generations, you'll want to put Whitefish on your radar this spring.

Located on the shores of its six-mile-long namesake lake, just west of Glacier National Park, Whitefish is a small mountain town but it offers delicious dining at over 40 restaurants, cafés, and bars as well as innumerable recreational opportunities both in an out of town. One such activity is unique in the United States: sections of the “Going-to-the-Sun” Road and Camas Road in Glacier National Park are closed to all vehicle traffic except bicycles and pedestrians. You can walk or pedal into the alpine, have the entire road all to yourself, and enjoy incredible mountain views that are completely unimpeded by passing cars.

Below is a list of our favourite springtime activities in Whitefish, Montana as well as a few pointers on how to blend in like a local. For more recreational ideas and to learn about how to "Be A Friend Of The Fish" visit ExploreWhitefish.com.

How To Partake In Favourite Springtime Activities In Whitefish, Montana And Be A Friend Of The Fish

Spot Wildlife In Glacier National Park

Encompassing over a million acres and 130 lakes, Glacier National Park is the perfect place to watch wildlife emerge from their winter slumber. Here you'll find every kind of Rocky Mountain species from bears to river otters as well as 260 species of birds and a thousand different types of plants. Migratory birds return to the park in the springtime and, because there are fewer leaves on the trees, it's easier to spot them as well as other animals. Plus, there are fewer travellers around to impede your views.

Because many of the trails are at elevation, there could still be snow or ice on shady sections so be sure to wear good footwear and Yaktrax or another type of traction device and carry hiking poles. If you prefer to stick to the pavement, you can also walk sections of the Going-to-the-Sun Road that are closed to vehicle traffic. For more about hiking trails in the park, visit the National Park Service website.

Be A Friend Of The Fish Tip #1: Always give wildlife lots of space, photograph them with a telephoto lens, and carry bear spray with you on the trails.

Ride The Alpine Roads

Whitefish offers not one but two unique experience for road riders in the springtime: sections of both the Going-to-the-Sun (GTTS) Road and Camas Road in Glacier National Park are open to bicycle traffic only. If access to one is limited due to plow activity, simply go to the other! Both offer the best scenic riding in America between late April and June: towering mountain peaks, fast-flowing rivers, beautiful meadows and plenty of roaming wildlife including bighorn sheep, deer, mountain goats and bears emerging from their winter dens. Remember to always keep your distance from wild animals and never approach them.

It should be noted that Glacier National Park has a vehicle reservation system for visitors wanting to travel the GTTS and more information about that as well as directions can be found on the 2022 Vehicle Reservations page.

For those in need of bicycle rentals, they can be arranged by contacting the following shops:

Be A Friend Of The Fish Tip #2: Biking into the alpine requires warm layers, including gloves, and a wind/rain shell.

Hike And Bike All The Other Roads and Trails

Thanks in large part to the Whitefish Legacy Partners, there's a recreational trail system called The Whitefish Trail that offers 47 miles of walking and biking, all accessible via 15 trailheads. Additional access can be found at the Whitefish Bike Retreat, a unique lodge and campground located eight miles out of town that caters to mountain bikers and outdoor enthusiasts. Particularly good in the springtime is the Whitefish Trail around Woods Lake, which includes three scenic overlooks with views of Woods Lake and the Whitefish Range. Plus, thanks to a 1.5-mile trail easement donated by the local Goguen Family, the trail offers stunning views of Whitefish Lake.

Some of the shadier trails may still have a bit of snow on them in the spring months but there are plenty of clear, open roads in the Flathead Valley in which to explore by bicycle. One of the best gravel bike experiences is riding the North Fork Road from Camas Road to Polebridge because it's mellow enough that anyone can do it, but the views are outstanding and you can stop at the Polebridge Mercantile for some mid-ride snacks before heading back.

For more information about biking the trails and roads around the Flathead Valley, check in with the guides at Whitefish Outfitters and the owners of the Whitefish Bike Retreat.

Be A Friend Of The Fish Tip #3: When biking or hiking, always remember to pack out your TP and trash.

Fish The Local Waterways

There's a reason Whitefish is called what it is. Founded in 1905 , the town earned its name because early settlers noticed the Salish people catching whitefish in the lake. In fact the Salish word for the area, epɫx̣ʷy̓u, means "has whitefish." There are a lot of other species in the surrounding lakes including trout, pike, and bass and state regulations allow anglers to fish lakes and reservoirs all year long including on Flathead Lake, the largest freshwater body of water west of the Mississippi, and on the 23,800-acre Hungry Horse Reservoir.

For those who prefer to cast in rivers and streams, there are innumerable locations in and around the mountains near the community including the Whitefish River but it's important to note that the 2022 fishing season runs from May 21 to November 30, unless otherwise noted in the state's fishing regulations. Here’s a map and more info for the various lakes around town: explorewhitefish.com/map.

Be A Friend Of The Fish Tip #4: Hire local guides. They know the secret spots! We recommend Lakestream Outfitters & Fly Shop.

Explore The Town

For a community of only 8,000 people, Whitefish has plenty of urban amenities to go along with its rural charm. It's recommended that every visitor checks out the Whitefish Depot, which is one of the busiest train depots between Seattle and Minneapolis. Built by the Great Northern Railway in 1928, and restored in the 1990s, this beautiful, historic building is noted for its beautiful timbers and small museum. Other places worth visiting include the Stumptown Art Studio, which is a nonprofit organization in downtown Whitefish that offers classes for adults and kids, rotating exhibitions, and drop-in open studio times for everyone to paint pottery or fuse glass with other creatives. If you'd rather buy art than make it, the Sunti World Art Gallery features award-winning painters work in oil, acrylic, pastel, and charcoal and adhere to old masters techniques, from authentic en plein air impressionism, to exceptionally detailed hyper-realism. For fashionistas, The Toggery needs to be on your radar because it's part upscale boutique, part rustic department store, and everything Montana.

When not shopping, rest and rejuvenate at one of the 40 cafés, wineries, bakeries, distilleries, restaurants, and breweries in town. Here is a list of recommendations:

- Bonsai Brewing Project

- Ciao Mambo

- Spotted Bear Spirits

- Unleashed Winery

- Fleur Bake Shop

- INDAH Sushi

- Loula's Cafe

- Wild Coffee Company

- Amazing Crepes

- Sweet Peaks Ice Cream

- Tupelo Grille

- The Last Chair Kitchen & Bar

Be A Friend Of The Fish Tip #5: Be extra kind to the workers in Whitefish. They're the backbone of the town.

For more info about Whitefish, Montana, visit ExploreWhitefish.com.

"Child Of The Setting Sun" - The Writing

Our Editor-in-Chief Mitchell Scott has penned one of the most incredible stories we've ever heard. It was just published on Patagonia's website. Here's the link.

"Ten minutes after the accident, holding Ian’s lifeless hand, Steph looked at Stephen, who was just a few months away from starting medical school, and asked, 'Do you think that we can recover his sperm?''I was totally floored and didn’t know what to say,' remembers Stephen. 'We needed to get out of there, but her comment left an enormous impression on me. It encapsulated everything that it meant to her at that moment: Losing Ian meant losing a future that they had envisioned for themselves.' And for Steph, at the time unable to grasp ever being with someone else, this meant the potential loss of motherhood.

Postmortem sperm retrieval, or PSR, is quite new and not without controversy. It is the act of removing sperm from a deceased man often with the intent to use it for in vitro fertilization (IVF), a process where a woman’s eggs are fertilized with sperm outside the body in a lab and then placed in the uterus. This process of posthumous conception has been banned in countries like France, Germany and Canada. In the UK, it requires pre-written consent from the deceased. In the US, there is no specific federal regulation surrounding PSR."

The above words are from the absolutely fascinating tale of Winthrop, Washington resident Steph Bennett and her son Robbie, who was conceived in vitro with semen taken from his father's body after he perished in an avalanche on March 4, 2018. Our editor-in-chief Mitchell Scott wrote the article and it was just published on Patagonia's website. Normally we don't tend to post material we write for other magazines or sites on MCG, but in this case we simply had. Take it from us that this is very much worth 20 minutes of your time to read:

https://www.patagonia.com/stories/child-of-the-setting-sun

For another fascinating story about an avalanche and survival, read our story "Buried 4 Metres Down – An Avalanche On Mt. Temple" by Dave Robertson.

Herding Together: Mountain Muskox Group Helps Survivors of Alpine Trauma

Mountain Muskox is a new group-therapy program offering hope for survivors of alpine trauma.

Survivors of a size-three avalanche should feel lucky. But for Adam Campbell and Kevin Hjertaas, emerging unscathed from a January 2020 slide kicked off a nightmare. The two were skiing in Banff National Park when an avalanche swallowed the third member of their group, Campbell’s wife, Laura Kosakoski. It took them an hour to dig her out of the debris; she died the next day.

After the accident, Hjertaas, who is a ski guide but wasn’t guiding that day, says he sunk into depression. Campbell was so low he considered suicide. Their story is not unique, except for what happened next: they were invited to take part in a new group-therapy program for survivors of mountain trauma, such as witnessing an injurious fall, responding to a crash, or experiencing a fatal avalanche.

https://youtu.be/kEYu6xkMKrE

“Counselling is an essential part of the recovery from big incidents,” says Janet McLeod, a registered psychologist. “But individual counselling has its limits.” Treating accident survivors at her Mountain Therapy clinic in Canmore, Alberta, McLeod noticed that shame led many to push away the people they needed most. She wondered if group counselling could help and facilitated a session for four clients. It went well. After the avalanche accident, they invited Hjertaas to join them.

Hearing the others share similar emotions to his own, Hjertaas stopped feeling so alone. “When people you respect understand what you’re going through, it’s more impactful,” he says. “You see they’ve experienced something similar and are doing better. I needed that hope.” The group formalized their sessions into Mountain Muskox, named for the way the Arctic bovines circle together to support and protect each other when they are threatened. With sponsorship from the Alpine Club of Canada, Arc’teryx, and the Association of Canadian Mountain Guides, a 12-session curriculum was developed. The pilot ran last year and included Campbell. He and Hjertaas say the process helped them heal, and McLeod deemed it a success. Some of the participants now want to train as facilitators so they can run more sessions and export the program to other mountain towns. McLeod says, “Watching these people who are so used to being strong and independent be vulnerable with each other is really powerful.”

A New Book Offers Up Amazing Old Photos of the Kootenays

The recently released Lost Kootenays book provides a glimpse back at a simpler time in the region, when things were more black and white. By Greg Nesteroff

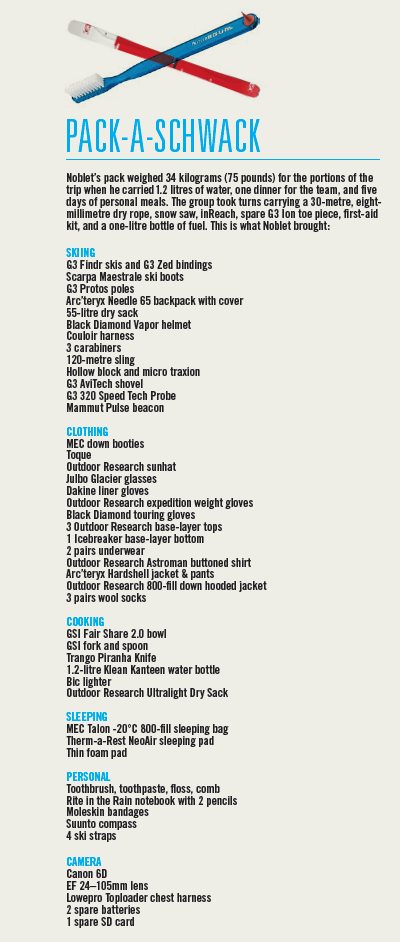

How do you choose 130 pictures from among thousands of fascinating images to create a photographic history of the Kootenays? This past year, Eric Brighton and I faced this daunting task when MacIntyre Purcell Publishing asked us to create a companion book to the popular Lost Kootenays Facebook site, which now has more than 50,000 followers.

We started by establishing some criteria. Since the book was to be black and white, we decided to cut things off in the 1950s, before colour photography became popular. Plus, we’d stick to only the best-quality photos. Grainy, blurry, or otherwise less-than-optimal images would be avoided. We also wanted to represent as many communities as possible: larger places might have several pictures each, but we were committed to featuring smaller locales too. Photos depicting people were preferred, particularly those under-represented in local history books, such as First Nations, Chinese Canadians, Indo Canadians, and women. We wanted pictures that have rarely, if ever, been reproduced. While some images in this book have been published before, most have not. Finally, we needed photographs that were affordable. We bought a few from the BC Archives, but at $70 per image, we used them as a last resort. In the end, we had surprisingly few disagreements; it was more like mutual agonizing over which images to cut. We could easily create several more volumes with the images we left out.

Above photo: Employees of the Crows Nest Pass Lumber Company (CNP) take a break to pose for an unknown photographer while working on a massive log jam on the East Kootenay’s Bull River, sometime between 1910 and 1914. In those days, rivers across the province were used as arteries to transport poles to mills, and many loggers were killed doing the dangerous work of clearing jams, such as this one. CNP was founded in 1902 by Scottish immigrant John Breckenridge and a few other business partners. It was based in the community of Wardner on Kootenay River, just south of the mouth of the Bull River, and was dissolved in 1957. Photo: City of Vancouver Archives. Top photo: Fernie, BC, suffered two destructive fires. The 1904 fire, seen here, levelled much of the town. Disaster struck again four years later when sudden winds caused a small forest fire to burn out of control. Within an hour and a half, most of the community had been destroyed and thousands were homeless. At least nine people died and damage was estimated at $5 million (roughly $184 million today). Photographer unknown/Royal BC Museum and Archives

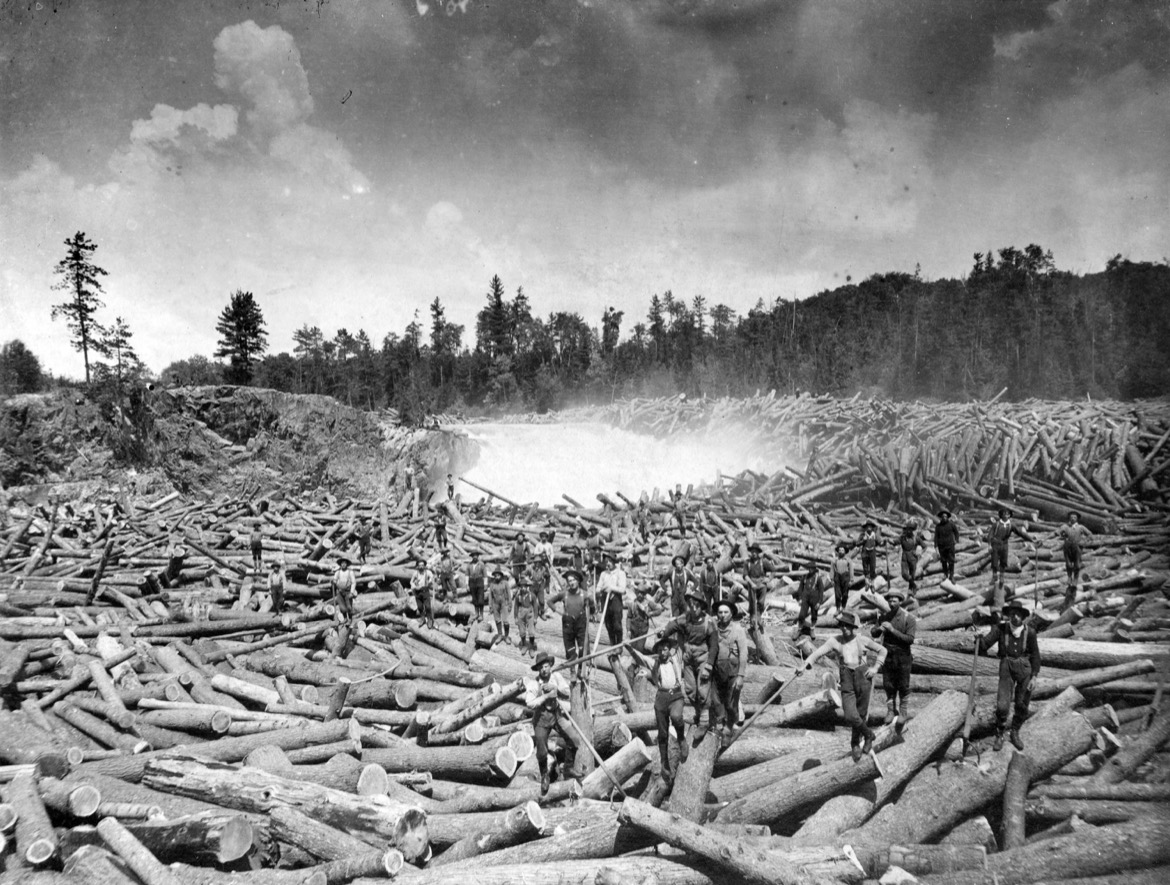

In 1905, the Kootenay Shingle Company of Salmo, BC, hired a number of Chinese-Canadian and Japanese-Canadian employees from the Lower Mainland. Their arrival by train sparked a near-riot by white settlers who felt threatened by labourers working for lower wages. The police had to intervene. Once the initial controversy died down, Japanese-Canadians worked in the woods around Salmo until the start of their internment in 1942. Photo circa 1910. Photographer unknown/Salmo Museum archives.

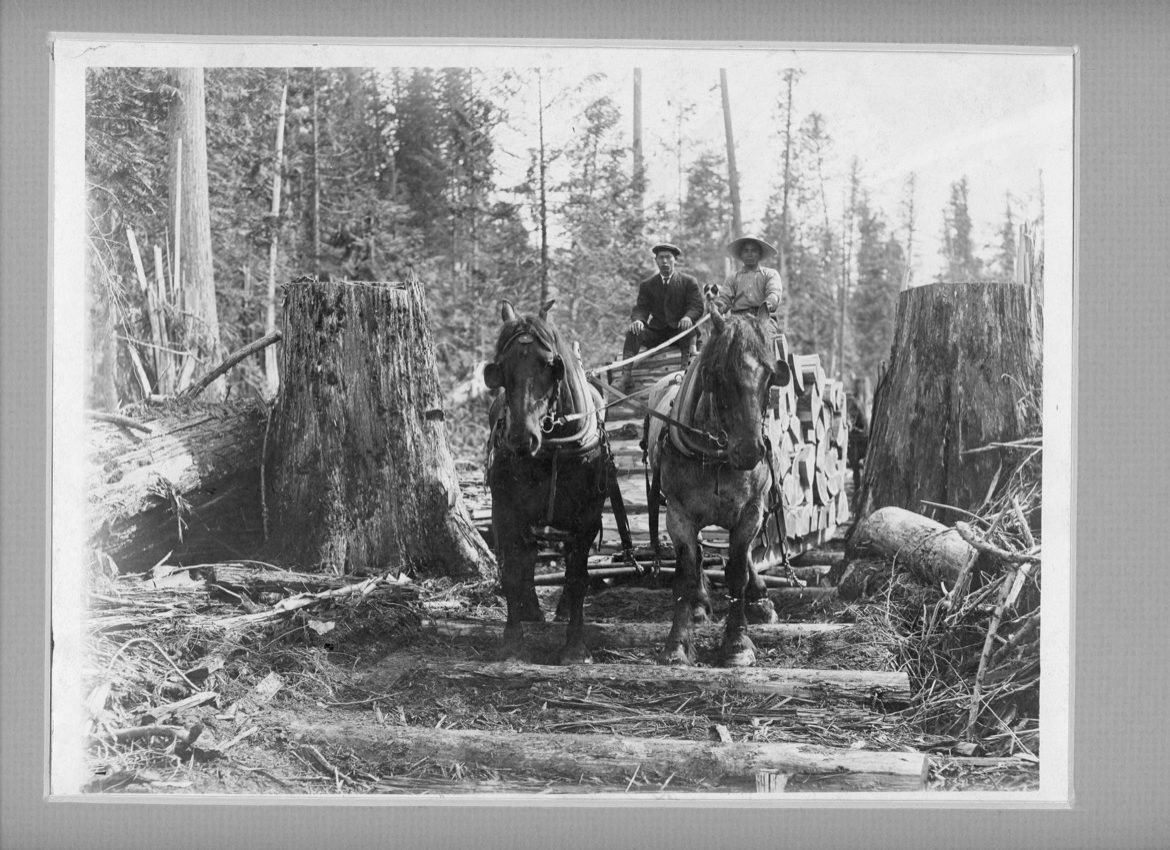

Taken in the 1940s, this photograph shows Doukhobors gathering for moleniye (prayer service) in Castlegar, BC, at the Belyi Dom, a meeting house built in 1911. The name translates to “white house,” referring to the building’s whitewashed exterior. It was demolished in 1949 during construction of the Castlegar airport. Photographer unknown/Greg Nesteroff collection

This photo came with the description “Ed. Young Chef and others playing musical instruments” and was taken in Galloway, East Kootenay, BC, between 1910 and 1914. Photographer unknown/City of Vancouver Archives

This photo turned up on eBay in 2018 and shows three tipis near the CPR wharf in Nelson, BC, circa 1892–93. The SS Nelson is in the background. Photo: Neelands Brothers/Douglas Jones collection

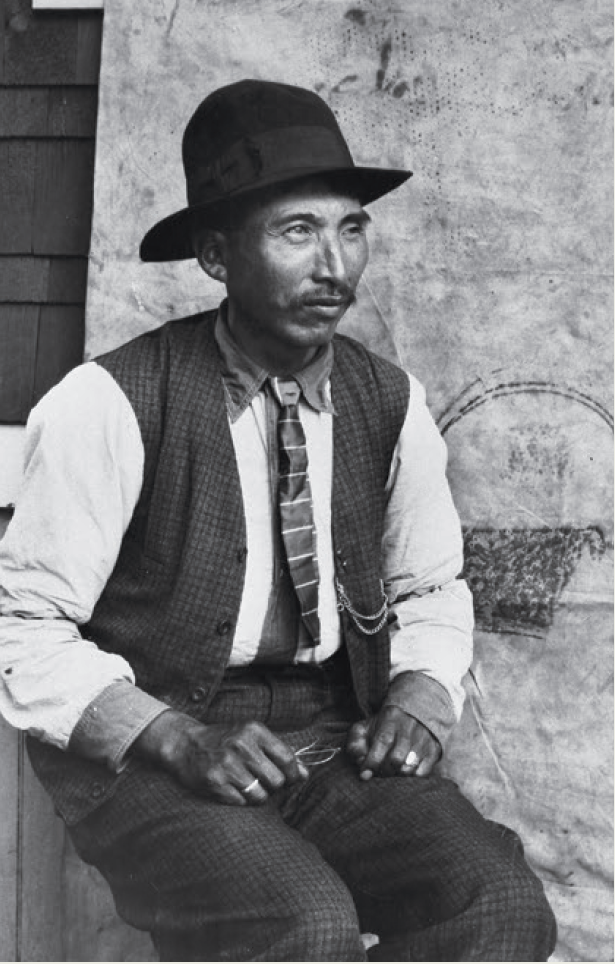

Alex Christian, also known as Pic Ah Kelowna or White Grizzly, was a noted hunter, fisher, guide, and a member of the last Sinixt family to live at kp’itl’els, at the confluence of the Kootenay and Columbia rivers. The purchase of land at that confluence by Doukhobor immigrants displaced the Christian family from their home, and their burial grounds were eventually plowed over by Doukhobor farmers. In 2009, Doukhobor leader J.J. Verigin publicly apologized to Christian’s grandson, Lawney Reyes. Photo: James Alexander Teit/Canadian Museum of History

The Canadian Pacific Railroad’s Pacific Express, Kicking Horse Canyon, near Golden, BC, circa 1890s. Photo: Norman Caple/City of Vancouver Archives

Sourdough Alley in Rossland, BC, 1895. This haphazard business district ran between Washington Street and what is now Esling Park, and a variety of stores did business while squatting on a railway land grant. The street was done away with after Rossland incorporated in 1897. Sourdough was a staple of a prospector’s diet, and the term “sourdough” came to mean an experienced prospector. Photo: Edwards Bros./City of Vancouver Archives

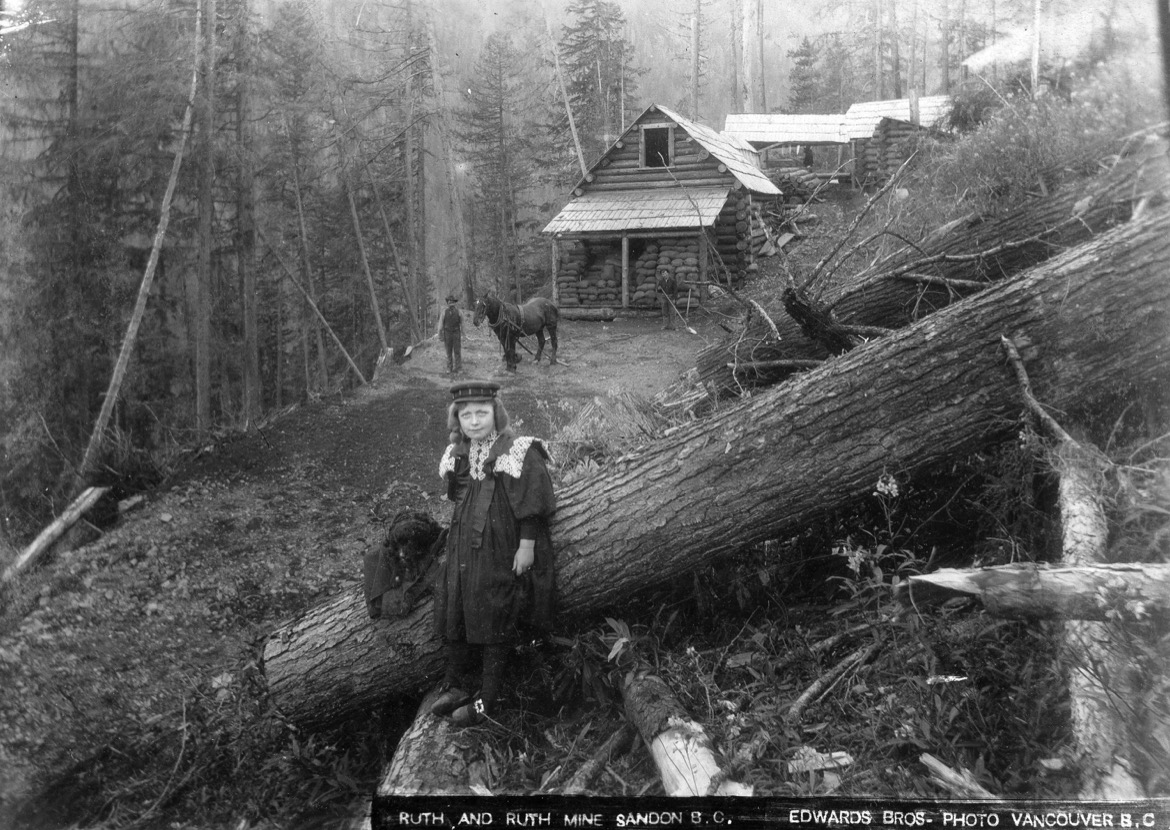

Ruth Mine, near Sandon, BC, 1890s. Is this girl the namesake of the mine? F.P. O’Neill located the claim in 1892 and combined it with three adjacent claims including the Hope, Wyoming, and Ruth Fraction. It was worked profitably for many years, yielding about 776 metric tonnes of silver, 10,000 tonnes of lead, and 1,600 tonnes of zinc. Some of the Ruth Mine’s abandoned buildings are still visible from Sandon. Photo: Edwards Bros./City of Vancouver Archives

Freediving Under Canada's Frozen Lakes

For Alberta athlete Lorenza Sommaruga Malaguti, freediving beneath ice truly takes her breath away.

A two-metre-wide maw of dark water licks at the surrounding ice, a glaring swath of white that extends across all 21 kilometres of Lake Minnewanka, near Banff, Alberta. Earlier in the day, a man clad in orange chaps and a dark wool toque wielded a chainsaw and cut through the 20-centimetre-thick ice to create this hole. Now, a tall woman with long blond hair tucked into the hood of her black wetsuit adjusts the straps on her fins, weight belt, and mask. She flexes her fingers in seven-millimetre-thick gloves, steadies her breath, and then plunges below the surface.

“Once you’re under, you can see the light penetrating through the ice, and it’s so amazing that you don’t think about getting trapped underneath it,” says Lorenza Sommaruga Malaguti, one of a handful of people in Canada who willingly swim under ice without supplemental oxygen. The Calgary-based veterinarian is describing a particular day in the middle of March when she slipped into the waters of Lake Minnewanka. “It’s the cold that you have to master. It takes over everything. When it hits your face, it’s such a shock. You’re literally dipping your bare skin into 1°C water and it’s excruciating. Your body is just trying to survive.”

Freediving is the act of swimming underwater while holding your breath, and according to archaeologists, we modern-day humans have been doing it to feed ourselves for at least 8,000 years. Lorenza, 33, and her brother Luca, 31, were taught to freedive for fish by their grandfather while growing up in Italy. After moving to Canada in 1997, they set about honing their skills in various places around the world, including Grenada, where Lorenza attended vet school, and Howe Sound near Squamish, British Columbia, where Luca now lives and runs the Sea to Sky Freediving & Spearfishing Academy.

https://youtu.be/kLnamCHR5fc

When he’s not teaching breathing techniques to freedivers, mountaineers, and other athletes, Luca travels the globe representing Canada at freediving competitions. The sport began in the 1950s when Italian divers challenged one another to see how deep they could go underwater and for how long. Luca’s deepest dive is 80 metres, and he says it’s standard for him to hold his breath underwater for two and a half minutes. “To prepare for a dive, we do some specific types of stretching to loosen up the respiratory muscles, as well as some meditation and visualization to get the mind into a positive place,” he says. “We call it the ‘flow state.’ When I teach this to my students, I use the analogy of race-car drivers because, although they’re ripping around the track at 300 kilometres per hour, their heart rate is super low. They’re present and focused and using all their senses in the moment.”

Lorenza admits she can’t dive as deep as her brother, but she’s better at handling freezing temperatures; Luca has yet to dive under ice. In warmer climes, she’ll stay underwater for longer than two minutes. “I’m happy to hold my breath for 45 seconds under ice. That said, I don’t do this because I want to breath hold,” she says. “You don’t go ice diving to do that. You go for the experience.” She then explains how lake water in the winter months is extremely clear because of the lack of sediment, so when she dives, there’s a crystalline light show below her that fades from turquoise to black, and above is sunshine refracting through ice. Listening to her description, one imagines it might be like looking at the world from inside a white cream-soda freezie.

If she's not floating under ice, Lorenza is speeding across it with the help of a kite. She’s ranked as one of Canada’s best snow kiters; she won bronze at the 2019 Red Bull Ragnarok, which is held on the Hardangervidda Plateau in southern Norway and considered the world’s hardest snow-kiting event. “Most things I do are adrenaline driven,” she says, “but freediving is my only sport where I have to calm down; I have to relax. And when I hit that freezing cold water, it takes another level of mindfulness. I’m not saying I’m good at it — I think my brother would exceed at ice diving because of his ability to meditate — but I can get to a state where I’m relaxing, where I’m conscious of my breath, where I’m not feeling the cold anymore. And then you go down.”

From Skis to Headlamps: Meet the Craft Gear Makers of the Kootenays

Canada’s first craft outdoor gear alliance is rolling out a #ShopLocalBC campaign in which Kootenay makers step into the spotlight.

Since the new year, we here at Mountain Culture Group have joined forces with the Kootenay Outdoor Recreation Enterprise (KORE), Canada's first ever craft outdoor gear alliance, to meet the local makers of everything from skis and boards to headlamps and backpacks. The purpose of the campaign is to bring awareness to the amazing outdoor equipment being made right here in the Kootenays and to touch on the importance of shopping locally. But we soon realized that this was about so much more than the gear being designed and sold from shops and homes in communities from Golden to Salmo: this was a people project.

The Kootenay region is a special place in the world where locals can easily balance work with lifestyle because the outdoors are so close at hand. That's why there's a burgeoning industry of designers and manufacturers of the gear we use while recreating here because the perfect testing ground is literally our backyard. Cam Shute of Darkhorse Innovations moved here decades ago so that he could test the gear he engineered on the mountains surrounding his home in Nelson. “Living in a place like Nelson is key to a lot of my work,” he says. “I can very quickly tap into activities so I can go from idea to prototype to testing in a very short amount of time.” That's also why Jonathan Quarrie moved to Rossland: to design and build noboards that he could test on the slopes that are less than a 10-minute drive away.

Cam and Jonathan are the type of people who are the core of what KORE stands for: independent, local, craft gear makers who are passionate about what they do. Another individual we met while working on the #ShopLocalBC campaign is Dylan Bucher, the owner of Lynx Off Grid Technologies, which designs and sells some of the world's smallest, most powerful headlamps. Dylan walks the walk: he lives on an off-grid property near Kootenay Lake and relies on solar panels to power his computer from which he runs his online store.

Like craft beer, craft gear is just better. Not just because it's made by individuals with a passion for the products, but because those same individuals care about the experiences you're having with those products. Jackie Brown and Christian Knowles, the owners of Ambler Mountain Works in Nelson are excellent examples because when they receive special requests regarding the toques, hats and slippers they design, they'll go out of their way to make it happen. When we interviewed them, they told us a story about how a customer owned one of their hats and wanted to replace it with the same one. Despite the fact that particular design wasn't available anymore, the couple went out of their way to create one. It's stories like those that make you appreciate the fact that shopping locally for your gear is better, not only because the gear is excellent quality but because the experience of buying that gear from a person who resides in your region and who's passionate about the product, is ultimately better.

Throughout this campaign we'll continue sharing stories like Ambler's through this website as well as via our social media feeds and KORE's. For more about the @ShopLocalBC campaign, visit: koreoutdoors.org.

About Shop Local BC

Funded by the Government of Canada and delivered through provincial and territorial chambers of commerce, the Shop Local initiative provides grants for programs and campaigns that encourage Canadians to shop local to help businesses navigate through and beyond the pandemic. The BC Chamber of Commerce is delivering the Shop Local initiative in British Columbia, ensuring that the program is inclusive, and funds are distributed equitably across seven economic development regions.

About KORE

KORE is an economic development and diversification initiative managed by the Kootenay Outdoor Recreation Society located in Kimberley, BC. It is an industry alliance of outdoor recreation gear manufacturers and designers in the Kootenay region and has brought together a network of 40+ craft gear makers and designers who have organically started up production manufacturing and designing within the Kootenays. KORE’s mission is to foster growth within the alliance through education, collaboration and connecting businesses to resources, grants, financing and capital, and to attract outdoor recreation product manufacturing and designers into the region to relocate or facilitate new entrepreneurial start-ups.

How One Newfoundland Man Changed Freeride Skiing Forever

THE YEAR WAS 1990. Backcountry skiing was, at least for the average recreational skier, the stuff of dreams. If you were a young person in ski lessons, you either raced the gates or bashed the bumps. Chances are you idolized Glen Plake, Doug Coombs, and Scott Schmidt, who had made skiing “extreme.” Maybe you even imagined yourself entering the famed Saudan Couloir Ski Race Extreme in Whistler, British Columbia. But a program, group, or association that could fan the flames of your passion to go off-piste simply did not exist. Not until a 31-year-old man from Newfoundland created the Rocky Mountain Freeriders.

Freeriding is a fluid, surfy style of skiing and snowboarding in natural terrain found away from groomed runs and human-made features. It was inspired by the golden era of extreme skiing in the 80s and 90s but refined by snowboarders such as Craig Kelly, who applied his seemingly effortless style in the halfpipe and big mountains. Freeride clubs are now a staple at many large ski hills in North America and Europe, and audiences around the world are entertained by events such as the annual Freeride World Tour, where competitors carve sweeping turns through backcountry runs, air off high cliffs, and throw down a 360 or two for good measure. In short, freeride has come to define mountain sports in the 21st century.

The adoption of the freeriding, or freeskiing, movement by young skiers can largely be traced back to one coach by the name of Guy Mowbray. Raised on the slopes of Marble Mountain Resort near the small city of Corner Brook, Newfoundland, Mowbray moved to the Canadian Rockies in the early 90s because of such iconic Greg Stump movies as Blizzard of Aahhh’s and Dr. Strange Glove. He took a job coaching young ski racers at Alberta’s Lake Louise Ski Resort and was fortunate to have such young phenoms as Eric “Hoji” Hjorleifson and Chris Rubens in his classes. After a while, though, he sensed they were being pushed out of the sport, partly because of the rigidity and rules of the racing scene. “Skiing is a lifelong passion, and I saw kids who weren’t going to keep with it,” he says. “We wanted to make a group or a gang where you go out with your friends and push each other.” So he enlisted the help of fellow coach Kevin Hjertaas and founded the non-profit Rocky Mountain Freeriders (RMF), the first club of its kind in North America.

“The program was all about having fun and creating lifelong skiers,” says Rubens, who is now a sponsored skier living in Revelstoke, British Columbia. “In more recent years, freeskiing has gotten a lot more serious, but it was never about that when we were younger. We just wanted to have a good time, and that’s what I think was so special about the Rocky Mountain Freeriders.”

It was with the RMF that Rubens and his classmates took their first avalanche-skills training courses, learned to study the snowpack, built jumps, and began to push the boundaries of the resort. “It was definitely the first place I ever started to learn about those things and even started to think about building jumps in the backcountry,” says Hjorleifson. “RMF was completely ahead of the industry....[Mowbray] just loved skiing so much and loved skiing so much with us. For someone to put that together for those kids — it’s a big part of the reason we found our way in the ski industry.”

That fun, friendly atmosphere combined with the technical background Mowbray and Hjertaas brought to the program in the variable terrain of the Canadian Rockies turned Rubens and Hjorleifson into “Rubens” and “Hoji.” The latter spends part of the year in Europe doing research and development for Dynafit and has a backcountry boot and a freeride movie named after him. Rubens works with Salomon Freeski TV and has appeared in such classic freeride films as All.I.Can and Into the Mind. But RMF is not just where they became professional skiers, it’s also where they shared their passion with younger generations, who continue to evolve the sport today.

https://youtu.be/0z81mFk5_0o

When RMF was launched in 1999, 12 skiers enrolled. Back then, Mowbray says the daily regimen involved warm-ups on the groomers followed by technical instruction, and then the group would go find features to play on. “My goal was to have them exhausted by the end of the day,” he says. “Mileage is one of the most fundamental things, but I also had to get them out there above and beyond their comfort zones. Get them to push it. Make them clench their butt cheeks a bit more.” Hjorleifson joined the second year and Rubens a year later, and together they “really set the pace for the club,” says Mowbray. The duo went on to become RMF coaches and took an approach that Mowbray describes as a “forum” in terms of discussions and mentorship. Over the years, they trained or worked with a veritable who’s who of freeriding stars, including Megan Sime, Izzy Lynch, Drew Wittstock, Jemma Capel, Keegan Capel, and Noah Maisonet. They also taught a young Calgary skier by the name of Carter McMillan. Mowbray says he would often see McMillan skiing with his dad at Lake Louise and eventually asked if he wanted to join the program. That encounter and the tutelage of Hjorleifson and Rubens helped McMillan become the influential freerider he is today, with sponsors including Blizzard, Tecnica, and Marker.

Mowbray still sees McMillan about once a year, riding the lifts with his friends at Revelstoke Mountain Resort, and he wonders what would have happened if he had not approached him that day. Would he still be skiing? He also thinks about decisions he’s made along the way, like leaving the Rocky Mountains and taking a job as a supervisor on the contentious Site C Dam construction site, which he says he had to get out of because it was such an awful scene. He now owns a landscaping company in Revelstoke and skis as much as possible. He admits to feeling sad when he heard the RMF was disbanding in 2019. At its peak, the club had 135 kids, but as race programs at Lake Louise started incorporating freeriding, there wasn’t a need for a standalone club anymore. Then Mowbray’s voice shakes as he says that founding the RMF and watching his students laugh, play, and become lifelong skiers in the mountains was the best thing he ever did.

Jake Sherman is a reformed ski racer turned freerider. In between graduate school and safety meetings, he may or may not have spun a lift around a bull wheel.

The T-bar is "One Beer Long" and 5 Other Reasons Why The Arrow Lakes Region is Awesome

Editor Vince Hempsall fell in love with Summit Lake ski hill while visiting the Arrow Lakes region on assignment recently. This is why.

I’ve driven past Summit Lake Ski and Snowboard Area dozens of times and always thought, “I should hit that place.” Located 19 kilometers southeast of Nakusp in the Arrow Lakes/Slocan Valley region, the hill offers a scant 150 meters of vertical and seven runs but it’s the grassroots vibe of it all that’s truly enticing.

The Nakusp Ski Club, a volunteer association, has operated the non-profit hill since 1961. About 15 years ago rising insurance costs almost shut it down but thankfully residents agreed to a small tax to help keep its lone t-bar chugging along.

https://youtu.be/mNq8_rZu_hg

Earlier this month I finally had the chance to cleave its slopes as part of an assignment for ZenSeekers. Fernie photographer Kyle Hamilton, Whistler videographer Chris Wheeler and I tailed the Garlinge family from Rossland on various winter activities in the northern Arrow Lakes area. We went snowshoeing on the Jack Rabbit Trail in the Nakusp Community Forest and enjoyed epic views of the Monashee Mountains to the West. We skied Summit, located above its namesake lake. And we lounged in the pools at the Nakusp Hot Springs complex, which is also community owned.

For more on winter activities in Arrow Slocan, visit ZenSeekers.com.

My favourite part of the trip was night skiing at Summit: every Friday evening the hill opens and for $20 skiers and boarders can access the one lit run, but that doesn’t stop them from shredding the other slopes with the help of headlamps. It’s the first time I’ve ever seen flashlights used to ski at a commercial hill. It’s also the first time I’ve heard someone refer to the length of a t-bar as “one beer long.”

In an era when lift tickets can cost the average family over $400 a day, it’s great to know places like Summit still exist where you can get an entire season’s pass for that amount. As for aprés, the hill’s lodge is more of a warming hut than anything so after polling some of those in the know, below is a list of the best places to grab food and drinks in Nakusp after a day adventuring. (It can be challenging to Google anything related to food in the area as many of the village eateries don’t have websites.)

- The Three Lions Pub has great fish and chips, burgers and sandwiches as well as beer on tap

- Arrow Lake Tavern is another good aprés choice

- The best pizza in town can be found at Arrow and Anchor Pizza

As for pre-ski options, Hoss & Jill’s Bistro does an excellent sit-down breakfast and Mountain Top Coffee has the best cuppa joe in town as well as some light snacks and baked goods.

For more about winter activities in Nakusp and the entire Arrow Lakes region, and to see photos and video from our assignment, check out the this ZenSeekers story.

New BC-Based Talk Show Airs At 10,000 Feet

Radio Chatter is a talkshow filmed in a Cessna airplane and this week's guest is celebrated British-Columbia photographer Taylor Burk flying over Mount Waddington.

Radio Chatter is taking the talkshow genre to new heights. Created by Victoria, British Columbia native Mathew Mosveen, the project films guests in a Cessna 172 aircraft talking about everything from what it's like being in one of Canada's most recognized bands to the nuances of photographing the country's most remote landscapes.

Founded in 2018, Radio Chatter is shot while pilot Mosveen navigates the plane with his guest in the passenger seat and episodes so far have been filmed in Montreal, Vancouver, Victoria, and Toronto. Guests have ranged from musicians and actors to athletes, entrepreneurs and artists and according to Mosveen, the aim of the show is to entertain and inspire while demystifying the magic of flight and showcasing the beauty of our natural environment. In the most recent episode he flies to the summit of Mount Waddington and documents BC-based photographer Taylor Burk in action shooting the province's tallest and most remote mountain. We caught up with Mosveen to ask him a few questions about how the project got started and what some of his favourite guests have been so far.

https://youtu.be/7HMkBAjPeWQ

Hey Mat, congrats on the show. It's a cool idea. What was the impetus for it?

I've been head-over-heels passionate about aviation since I was two years old. In fact, I have plenty of early memories being around airplanes and many of my childhood photos are around planes 'cause I loved them so much even though there was never a flying background in my family. I got my license at age 16 and remember taking my friends flying throughout high school and college and for them it was as magical as the first time I got to fly. So by taking others flying I get to constantly experience my passion through the lens of somebody who hasn't done it thousands of times before. It keeps it all interesting for me because I'm terrified of it ever becoming boring or routine. I figured I could share that passion with the world with a show in which guests are always like, "Wait you want to take me in a plane? Over a mountain? Ahhh... sure!" It's way more fun than interviewing them over a cup of coffee.

What have been some of your favourite episodes so far?

Gosh it's hard to pick. The lazy answer is the most recent one with Taylor. He has been to almost any mountain you can think of so this was about the only one that would have been a first for both him and I. It was a bucket list item for every single person on the adventure. Besides that, this episode was also special because of the amount of work it took to make it happen. We tried three times over eight months and had to cancel on the day of, or day before, because of weather. There are very few useable weather days in that remote part of the province plus reporting is hard to come by: there's one weather camera up there that takes a single picture every 24 hours so you have to interpolate the reports from places like Powell River which are far away. We even Googled local places to ask them, "Hey how's it looking up there today?" The guys at White Saddle Air really helped us out that way. Plus we had to have tons of backup plans for any scenario like search and rescue, survival gear, that kind of thing because it's a wilderness that has to be treated with the utmost respect. We actually did have challenges on the day of shooting too: an aircraft experienced a brake failure early in the day, which was caught during the pre-flight checks, so we had to delay the shoot and get another plane while that one went to maintenance. It all worked out though because the two-hour delay put us at golden hour which made for insanely good lighting. We flew home at sunset!

I also like this episode because the production quality shows just how far the show has developed. It was the first time we did air-to-air shooting where we had another aircraft in a safe distance away with photographers and zoom lenses photographing us. It was also pretty funny since Taylor himself is a creator so some of his own shots that we were captured during the interview ended up in the show.

How did you and Taylor connect?

He was the first guest who ever found his own way to the show. Up until now I've spent lots of time approaching potential guests and pitching the show. Taylor, on the other hand, actually saw the episode with Yukon Blonde's Jeff Innes and reached out to via the Radio Chatter instagram account. He didn't ask to go on the show, all he said was "Love the concept for these interviews, super unique! Also Jeff is hilarious. Nice work!" But it felt crazy that somebody so notable would reach out to me. So I asked him to come on and he immediately said he'd be honoured.

For more about the Radio Chatter talkshow, visit the YouTube channel.

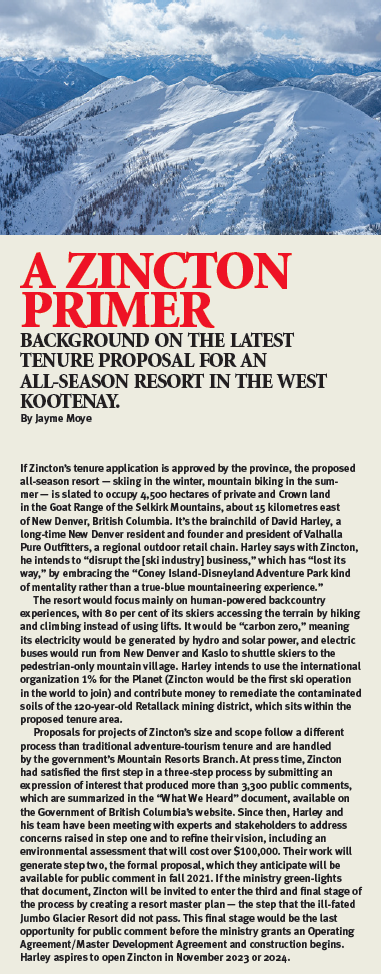

Tenureland: Why Adventure Tourism Tenure in the Kootenays is so Divisive

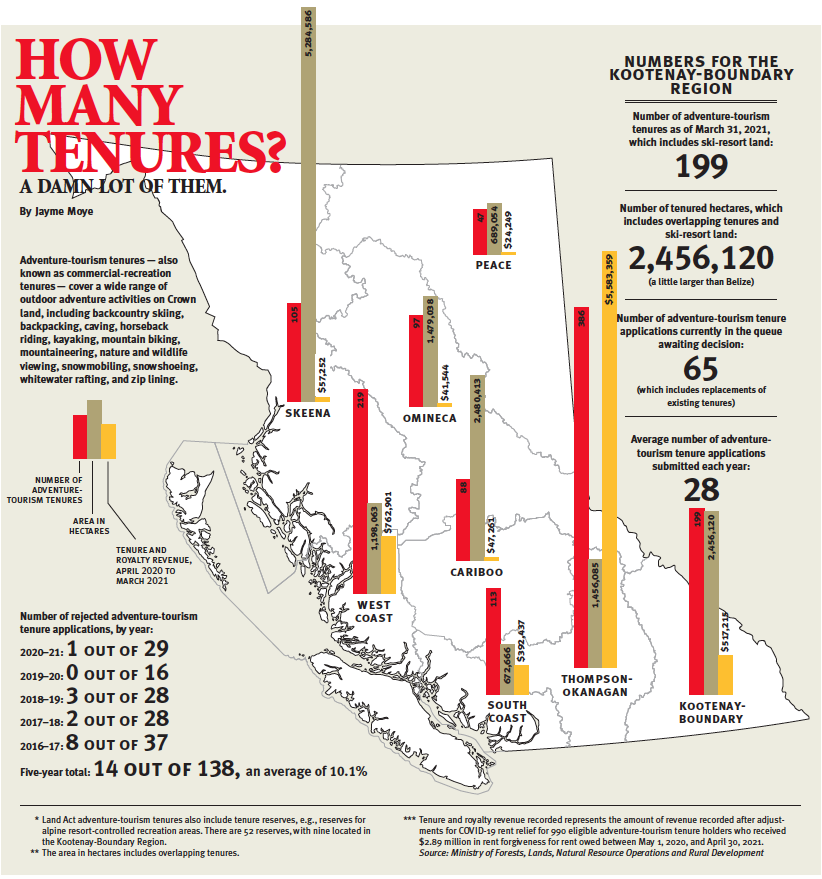

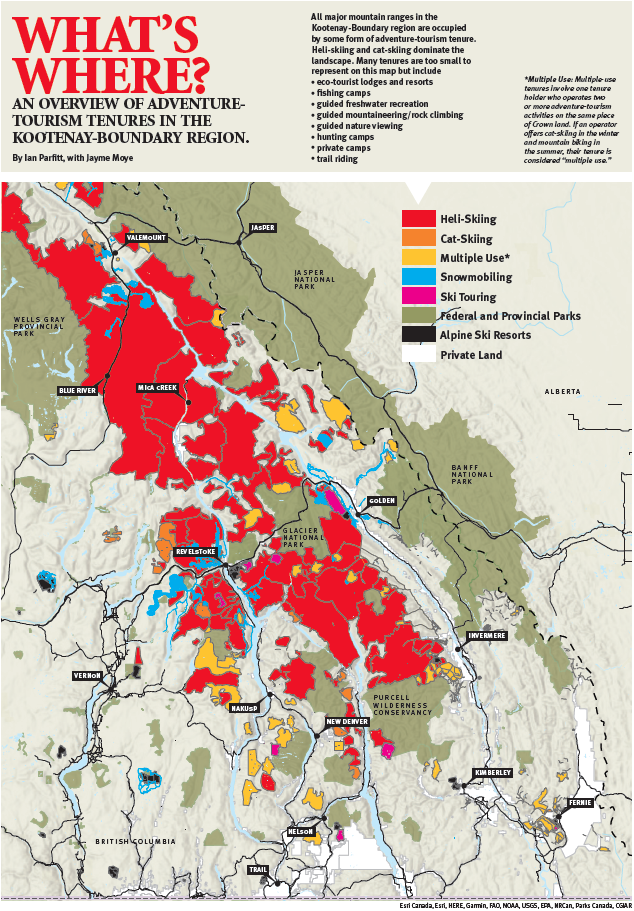

Backcountry skiing has exploded in popularity. In the West Kootenay region, the sheer number of adventure-tourism tenures is causing conflict among users and instigating impassioned pleas from the public for the government to press pause on the process. Residents of one East Kootenay town have weathered that storm by developing a local multi-user approach of patient collaboration that has pushed — and literally altered — everyone’s boundaries. By Jayme Moye. Illustration by Ian Johnston.

ALEX ROSS HAD A KOOTENAY dream to offer guided ski-touring trips out of a yet-to-be-built backcountry lodge through his fledgling business, Fresh Adventures. He would helicopter a small group of guests into his chosen area and fill their week with unforgettable powder days, long evenings by the fire, good food, and friends. The steps from dream to reality seemed straightforward: First, Ross filled out an application for tenure, which would grant him permission from the provincial government to operate commercially on Crown land. Next, he placed two ads in the local newspaper notifying the public of his tenure application and soliciting feedback. That’s when “Kootenay scrutiny” smacked him in the face.

Ross, who is originally from Toronto, had unknowingly chosen a section of Crown land just north of Nelson, British Columbia, that included a relatively new recreation site called West Kokanee, which prohibits commercial use. It also overlapped with a hallowed locals-only powder stash near the south boundary of the region’s beloved Kokanee Glacier Provincial Park. Last March, when word got out on social media about the tenure application by Fresh Adventures, Ross experienced an intense backlash. He was inundated with hundreds of emails and Facebook comments opposing his business and berating his apparent disregard for local backcountry ski-touring turf and the disruption he would cause residents, wildlife, and the environment by using a helicopter to shuttle guests to his proposed lodge. Multiple industry partners cut ties with his business. Ross’s favourite ski buddy disowned him, forcing Ross, who lives mostly out of his van, to change his mailing address from that friend’s place in Nelson to another friend’s residence in Vancouver. “Suddenly, I was a leper,” Ross says, “the evil empire trying to kill everybody.”

The tenure process has become so divisive that numerous groups are trying to find their own solutions to address what they see as an overcrowded tenure landscape.

Tenure is a touchy topic in the Kootenays. Multiple tenure holders who already operate successful backcountry ski lodges declined to go on the record for this story because they’re afraid of Kootenay scrutiny. If they try to expand their tenure area because, for example, they’re trying to steer clear of a herd of mountain caribou or there’s demand to add a new operating season to their business — like mountain biking in the summer — their tenure addendum application must first go up for public comment. And it can get ugly. “I can’t go to the farmers’ market or a school event without someone unloading their opinion on me,” says one well-established local tenure holder, who wants to remain anonymous. “No matter what I say, I’m going to get crucified.”

The tenure process has become so divisive that numerous groups are trying to find their own solutions to address what they see as an overcrowded tenure landscape. But perhaps the best approach dates back to 1995, when a grassroots organization in Golden, British Columbia, became a model for creating policy at a local level; they developed a framework for a sustainable regional tenure system that serves everyone’s interest in the backcountry — and they enforce it with the support of the provincial government.

BRITISH COLUMBIA'S LAND ACT is a tool used by the provincial government to manage Crown land, which encompasses 94 per cent of British Columbia’s land, rivers, and lakes. The act makes it possible to grant tenure. In addition to commercial-recreation tenures (also known as adventure-tourism tenures), the Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development also grants tenure for a wide range of commercial activity, including forestry, mining, and hydroelectric power.

Adventure-tourism tenures span everything from guided nature walks to whitewater rafting to heli-skiing. Basically, if you want to earn money through outdoor recreation on Crown land, you can’t do it legally without holding tenure.

"I can’t go to the farmers’ market or a school event without someone unloading their opinion on me. No matter what I say, I’m going to get crucified.” — Local tenure holder, who wants to remain anonymous

The amount of land granted under tenure is based on the activity. If you’re a small, family-owned business offering human-powered ski tours out of a 14-guest lodge, like Valhalla Mountain Touring, your tenure will be sized accordingly — 3,865 hectares in this case. If you’re Canadian Mountain Holidays (CMH), the world’s largest heli-skiing and heli-hiking company, with 11 luxury lodges, you’ll hold multiple tenures across southeastern British Columbia for a combined 1.2 million hectares, which is larger than some European countries.

As of March 31, 2021, there were 190 adventure-tourism tenures in the Kootenay-Boundary region — the area starting at the United States border and extending north past Revelstoke to Kinbasket Reservoir. The region includes the Selkirk Mountains and the Purcell Mountains, as well as parts of the Columbia and Rocky Mountains. The Monashee Mountains fall just outside the region to the west. The Alberta border is the boundary on the east. In the past five years, the ministry has received an average of 28 new adventure-tourism applications each year, which includes replacements for existing tenures. They granted tenure for 90 per cent of those applications, or 124 tenures. Tenure length is typically 30 to 45 years.

The catchphrase “Kootenay scrutiny” was coined by long-time Nelson resident David Lussier, a certified mountain guide and founder of the well-respected company Summit Mountain Guides. In 30 years, he has watched the Kootenays go from a sleepy winter haven to the heli- and cat-ski capital of the world. “The bathtub is full,” he says. In addition to being at capacity, Lussier says one of the public’s biggest complaints is that new adventure-tourism tenure applications continue to come in for areas the public has already rejected applications for in the past. “It’s frustrating,” Lussier says. “The public keeps saying, ‘Hey we don’t want this here,’ and the government isn’t doing anything about it.” Lussier can think of at least three adventure-tourism tenure applications in the past decade from people trying to do the same thing that Alex Ross wanted to do with Fresh Adventures, in the exact same spot.

WINTER BACKCOUNTRY RECREATION is exploding in popularity. Avalanche Canada, which over the past five years has taught roughly 10,000 to 11,000 students each season in its avalanche-skills training courses, reported an unprecedented jump to 15,029 participants in 2020–21. Over the past 20 years, Lussier estimates a 500-per cent increase in participation in the Kootenay-Boundary region. There are a record 379 Association of Canadian Mountain Guides (ACMG) guides living and working in the Kootenays.With more people accessing the backcountry, many locals, like ski tourer and snowmobiler Pierre Kaufmann, the retired founder of the Valhalla Wilderness Program for kids, have been advocating that the ministry leave some Crown land uncommercialized. But Kaufmann feels that is not in line with their mandate. “Their job is to sell tenures,” he says.

At the end of the winter 2020–21 season, Kaufmann and other residents of the Slocan Valley formed the Valley Backcountry Society to fight for leaving the last bit of Crown land free from business interests. They were spurred to action by another tenure application, by independent guide Conor Hurley, for a powdery valley south of Valhalla Provincial Park. Like Ross’s application, it encroached on one of the few remaining places without a pre-existing adventure-tourism tenure.

Kaufmann and his cohorts understand that adventure-tourism tenures are non-exclusive and that a tenure holder cannot, by law, prohibit the general public from recreating

on the land. But there is a difference between theory and practice. And not because heli-ski operators are harassing local ski tourers by swooping their choppers unnervingly close, although Kaufmann has had that happen. It’s more to give the right of way to the people trying to run tourism businesses that market remote backcountry solitude. “The status quo is, generally, we stay away from tenured areas and respect their space,” Kaufmann says.

Whether or not that’s how the provincial government intended adventure-tourism tenures to work, it’s how tenure is largely interpreted by local residents. There’s also an ideology among some that the commodification of the backcountry should be avoided at all costs. “For a lot of us, we just want to go into the wilderness and leave our economic order and all our man-made structures [behind] as much as possible,” says Kaufmann.

But of all the user groups struggling with coexistence on Crown land right now, the biggest one might be wildlife.

The mission of the Valley Backcountry Society is to take select pieces of Crown land out of the tenure equation completely, such as the area south of Valhalla Provincial Park and another basin in the Valkyr Range, which shall remain nameless. (“I hope you don’t give specific references to those zones,” Kaufmann requested. “Locals will kill me.”) To do that, they’re lobbying Recreation Sites and Trails BC to enact Section 56 of the Outdoor Recreation and Forest Ranges and Practices Act, which enables the ministry to “establish, vary the boundaries, or disestablish interpretive forest sites, recreation sites and recreation trails on Crown land.” It’s one way to try and balance commercial interests, but the society’s ambitions have raised more than a few hackles in the guiding community. As Lussier explains, if a swath of prime winter terrain becomes a recreation site, independent guides can no longer bring clients there, which Lussier does not agree with.

Hurley thought he was doing the right thing when he submitted his Valhalla Ranges tenure application as an independent guide. To work in the Kootenays as a guide, you must either be hired by a big snow-cat or heli-ski operator or operate independently on park land (using the government’s permitting process) or Crown land (using the tenure process). Hurley chose the latter. According to the government’s Adventure Tourism Policy, for Crown land that has an adventure-tourism tenure already on it — and most do — independent guides are subject to “incidental use,” which involves notifying the tenure holder and sticking to “low impact” ski-touring activities, including “occasional motorized air access, carried out in a dispersed manner.” On Crown land that doesn’t have a competing adventure-tourism tenure already on it, independent guides who want to operate beyond incidental use, as Hurley hopes to do, need to apply for a tenure of their own. And, apparently, be ready to dodge bullets. Hurley received strong public criticism. He declined to comment for this story, and his tenure application is still pending.

“It gets complicated,” says Kevin Dumba, the executive director of the ACMG. “There’s definitely value in having certified guides on the landscape out there; we just have to see if we can find a way for everybody to coexist.” In response, the ACMG created the West Kootenay Working Group. Dumba hopes it will act as a communication bridge between guides and the general public and stave off additional conflict and potential ill-will. Some of the most opinionated players are part of this working group, including Lussier and Kaufmann, who don’t often see eye to eye.

The owner of Valhalla Mountain Touring, Jasmin Caton, was upset because she recently learned that a slope containing one of her business’s landmark backcountry ski runs was about to be clear-cut.

Current tenure holders also worry about coexistence, but from a different vantage point. This past summer, the owner of Valhalla Mountain Touring, Jasmin Caton, was upset because she learned that a slope containing one of her business’s landmark backcountry ski runs was about to be clear-cut. Tenures are non-exclusive, remember, which means they’re also shared among industries — in Caton’s case, with forestry. “It’s frustrating,” she says. “It feels like everything is set up to support and facilitate those more extractive industries.”

But of all the user groups struggling with coexistence on Crown land right now, the biggest one might be wildlife. The Kootenays encompass large tracts of undeveloped land, making it home to one of the most diverse and dense populations of large animals — like grizzly bear and caribou — in North America. Local environmental groups are concerned that the current tenure process doesn’t account for the cumulative impact of the ever-growing number of commercial and industrial tenures on Crown land, combined with the rapidly increasing amount of recreational use. Environmentalists have also pointed out that most of the region’s national and provincial parks are now completely encircled by adventure-tourism tenures, which could be negatively affecting critical wildlife corridors that connect protected land.

The government’s land-use plan for the Kootenay-Boundary region is from 1997, and Butler and Raynolds believe it’s woefully outdated, to the point of irrelevancy.

Who speaks for the wildlife? Kimberley, British Columbia-based Wildsight monitors every adventure-tourism application and makes science-based recommendations during the public comment process. And according to the provincial government, all tenure applications are referred to the ministry’s regional wildlife staff, who have expertise about the nature and scope of local wildlife and its habitat. Sometimes this results in change, like when the Campbell Icefield Chalet, on the west slopes of the Rocky Mountains, added a wildlife mitigation plan to its application for summer usage in an area that contained critical rearing habitat for grizzly bear cubs. But Wildsight Conservation Officer Eddie Petryshen says it often falls on deaf ears. “We have the science now,” he says. “We know things about grizzly bear and wolverine, but the province’s guidance around those things hasn’t changed since the science came out.”

One of the most environmentally contentious areas in the Kootenays is the stretch of Crown land surrounding Highway 31A between New Denver and Kaslo. With Goat Range Provincial Park to the north and Kokanee Glacier Provincial Park to the south, it’s an important corridor for large and small mammals. It’s also classic Kootenay ski terrain: not too steep and oh so deep. As such, it’s densely packed with adventure-tourism tenures — 11 in total — which are held by some of the region’s most popular winter outfitters, including Retallack and Stellar Heliskiing. Last winter, when an expression of interest came in for Zincton (see sidebar), the first step in a three-part process to build a new ski resort within this area, environmentalists called it a step too far for wildlife. Zincton’s application prompted a local non-profit, Wild Connection, in partnership with the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative (Y2Y), to demand a moratorium on all new adventure-tourism tenures and the expansion of any existing ones until a land-use plan can be completed for the area.

“It’s the lack of government planning and management that’s actually at the heart of all this, rather than the tenure process.” — Dave Butler, director of sustainability, CMH

"There’s a lot of people feeling like the solution to managing all the conflict [on Crown land] is to have a good planning process,” says Nadine Raynolds, a Silverton, British Columbia-based program manager with Y2Y. “I think in this situation you actually have a lot of common ground.” She could be right. Of the 21 people interviewed for this story, both on and off the record, no one was opposed to land-use planning. In fact, most were vehemently for it. “It’s the lack of government planning and management that’s actually at the heart of all this, rather than the tenure process,” says Dave Butler, director of sustainability for CMH. “Tenure is just one of the tools that’s used to make things happen on the landscape.”

The government’s land-use plan for the Kootenay-Boundary region is from 1997, and Butler and Raynolds believe it’s woefully outdated, to the point of irrelevancy. Vera Vukelich, a manager of land policy and programs at the ministry, says creating new land-use plans is a big priority, and in 2018, the provincial government committed $16 million to work collaboratively with Indigenous governments, communities, and stakeholders to modernize land-use planning.

But ending the conflicts over powder in the Kootenays is not at the top of that land-use list, or even on the current list. “The BC government has been engaging with Indigenous governments and stakeholders to identity high-priority project areas,” says Vukelich. There are five projects currently underway across the province, and the two in British Columbia’s Interior are near Merritt and Fort St. John.

Here’s a compelling point: if the government does not prioritize your region, land-use planning can happen purely among citizens and then be proposed to the provincial government after the fact. That’s how it’s been done in Golden, Revelstoke, Cranbrook, and, most recently, in the Valemount area. While the plans are not legislated in all cases, the government has committed to following them for the purpose of providing resource-management direction on Crown land. The plans are also typically shared with aspiring tenure applicants before they put in an application, and the ministry refers to the plans when making decisions about which tenure applications to approve. “The land-use plan they did in Golden is landmark,” says Lussier. “They got everybody on the same playing field. It’s amazing what they did.”

During the 1994–95 winter in the Golden area, heli-skiing operators and snowmobilers were at each other’s throats because being in the backcountry together was getting dangerous. A few of the key stakeholders begrudgingly formed the Golden Backcountry Conflict Resolution Committee. They honed in on the most contentious area — a 200,000-hectare expanse — and started hashing out what type of activity, if any, made sense for each drainage. It took them four years and a lot of ripped-up maps, but they completed their plan in 1999 and presented it to the provincial government.

Local environmental groups are concerned that the current tenure process doesn’t account for the cumulative impact of the ever-growing number of commercial and industrial tenures on Crown land, combined with the rapidly increasing amount of recreational use.

At that time, the ministry employed multiple land-use planners for each region, two in Golden alone. Darcy Monchak was one of them, and he was assigned the task of formalizing the work of the grassroots committee and then expanding it to include all one million hectares of the Golden Timber Supply Area. Monchak gathered more than 50 people across 10 different sectors, including forestry and environment, sat them down together over “tens and tens and tens of meetings” and created the Golden Backcountry Recreation Access Plan. The group mapped every single drainage and wrote detailed descriptions about what type of land use was permissible and what wasn’t. When they finished, in 2002, Monchak, who has since retired from the government, says they’d managed to come to a consensus for the majority of the area, about 90 per cent. For the remainder, they agreed to let the provincial government decide. The ministry approved the landmark plan in 2003.

Today, a volunteer advisory committee keeps the access plan going. Chair Jason Jones doesn’t mince words about maintaining a functional land-use plan among potentially warring user groups. “We definitely have some difficult conversations, and we have to make some difficult decisions,” he says. Part of what helps the group stay cohesive is that the 10 sectors involved have been there since the beginning, and some of the representatives, like Butler from CMH, are original members. “There’s a lot of respect for the process, and people are in it for the long haul,” says Jones.

Precisely because local residents are so passionate, Monchak believes the West Kootenay is in an ideal situation for grassroots land-use planning — the kind that will stand the test of time and become a revered process. “Without the local committee keeping the plan alive, I don’t know where it would be today,” he says. “The reason the Golden plan succeeded is the committed members of the community here.”

Jayme Moye is an award-winning journalist based in Nelson, British Columbia. She hopes that writing this story won’t negatively impact her experience at the farmers’ market

Are You A Local?

From the editor's introduction of the 20th anniversary issue of Kootenay Mountain Culture magazine, editor Vince Hempsall questions whether he's a Kootenay local.

Whenever someone asks me, “Are you from here?” or “Are you a local?” I hesitate. Do I have to be born in the Kootenays, I wonder, or is it enough that I feel like a part of the social fabric that makes up this community? The question also reminds me of a game I played while travelling overseas 20 years ago.

It didn’t take long to realize there are four questions every fellow traveller asks: What’s your name? Where are you from? Where have you been? Where are you going? Most of the queries referred to location. Perhaps that’s because geography is an easy way to establish common ground, like how, for the past two decades, this magazine has been connecting people to a mountainous area of the world they love. I learned place isn’t the only thing that defines us when, as a game, I began altering my questions. “What does your name mean?” I’d ask other tourists waiting in line with me at internet cafés. I’d inquire about their favourite foods, what makes them happy, and I’d ask, “Where do you wish you were from?” I discovered fascinating details about people and connected with them on a far-deeper level than the simple “where” of their worlds.

On that trip, I met an Israeli guy in Sumatra, Indonesia. We were lying in colourful mesh hammocks outside a traditional Batak house with a roof shaped like water buffalo horns, and he was complaining about his country’s mandatory conscription into the army. “If you could choose anywhere on Earth, where do you wish you were from?” I asked him. “Does it have to be on Earth?” he replied. “Because my first thought is the stars.” Then he paused, looked up past the palm fronds into the cloudless sky overhead. “I suppose that’s redundant, though,” he said. “We’re all just star dandruff.”

Enjoy our 20th-anniversary issue, which is all about connections.

— Vince Hempsall, editor and Manitoba-born Kootenay local

(Feature photo by Paul Zitzka)

Hold On and Let Go: Tragic Loss Leads To A Climbing First

A professional climber's quest to complete every route in the famous Haffner Cave – in one day – gave him a way back to life. By Gord McArthur. Feature image by Tim Banfield.

At the start of the day, I was climbing nervously. I was feeling emotional and found it hard to focus, although I was in a familiar place. I’m a professional climber, and I’ve spent many days in Kootenay National Park’s iconic Haffner Cave, also known as the Hoar House, building my resumé as a mixed climber. The cave is home to the original try-hard mixed climbs, ranging from M7 to M12. But grief had been causing my mind to spin.

Over the years, I’ve lost many friends, especially in the climbing community. With every loss, I think I know how to deal with grief, yet each death feels like I’m experiencing it for the first time. I was taught to suck it up and keep moving, which seemed to work until last November, when I received the news that my friend took his own life. Less than 30 minutes later, I was on the phone again: my 30-year-old brother had just died in an accident. My soul shook and my heart fractured.Everything felt too heavy, and I couldn’t comprehend the losses. For three months, I barely did anything except get through the days. Then my good friend Sarah Hueniken invited me out for a day of climbing in Haffner Cave. Sarah had been dealing with grief of her own and the notion of being around someone who understood my feeling of drowning was reassuring. I made the effort to go.

After my initial bout of nervousness in the cave, something suddenly shifted in me. Sarah’s enthusiasm snapped me out of my funk, and I just started to move. Oddly, I was happy to try which-ever route she pointed at. It didn’t matter what grade it was. As we climbed, Sarah talked with excitement about her project to climb the cave’s seven routes in one day. Will Gadd had done it several years back, and she wanted to attempt the same goal. I could feel her motivation running through me; it was familiar. Sarah encouraged me to try it too, and her enthusiasm and belief in me struck a chord. Feeding off her energy and without thinking, I responded, “Hell, yes!”

A few days later, Sarah completed the cave’s tick list in a day. Her level of talent in that type of terrain is incredible. I was so excited for her. I, however, instantly lost motivation. My soul-crushing grief was all-encompassing, and I couldn’t give anything else my true attention. As days passed, I resisted attempting the feat. But something was gnawing inside. This is what you do. This is who you are. I realized each of us contains the possibility of something extraordinary, and those opportunities arise when we push ourselves toward the edge of our abilities. I was beginning to believe —and so I tried.

I grew tired and cried, wanting to give up.

Starting at 9a.m. in Haffner Cave, I climbed. I clipped the anchors route after route. After a while, I grew tired and cried, wanting to give up because it was too much pressure and effort. Every part of my being was pushed to the limit, but photographer Tim Banfield and belayer Greg Barrett, as well as a cave full of like-minded enthusiasts, had unwavering confidence in me, reminding me I could do it. Just before we needed to turn our headlamps on at the end of the day, I clipped the last anchor and everyone cheered. I had climbed all seven original routes and the newest addition to the cave, making me the first person to climb the eight routes of Haffner Cave in a day. It’s one of the hardest things I’ve ever done.

I felt freedom in that moment. Every step, tool placement, and sequence of moves made me confident and brought me joy. In the cave, Sarah reminded me that climbing helps me breathe and will always bring me peace. Grieving is hard, and without my family and friends, it would be unbearable. But what matters most is that we start that process, however it looks, and Sarah will always be the one who inspired me to believe I could take that first step forward.

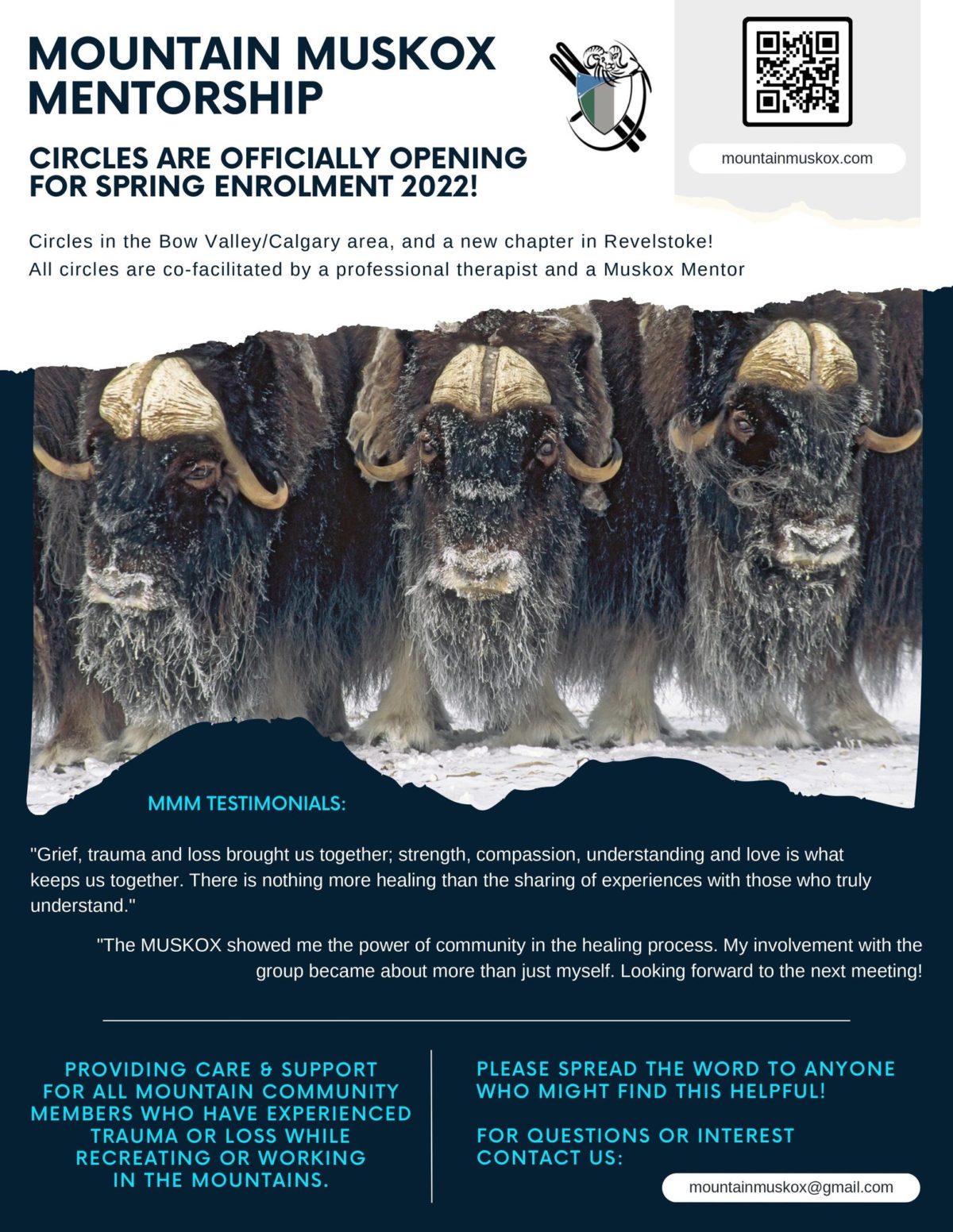

Win a Season's Pass to Red Mountain Resort

Red Mountain Resort in Rossland, BC, is one of our favourite places to shred. And it's that much better when you win a season's pass to ski it for free.

We're ringing in 2022 by offering a free season's pass to Red Mountain Resort for one lucky winner. Happy New Year indeed!

Mountain Culture Group has teamed up with The Crescent at Red Mountain Resort and are giving away a free 2022/23 season's pass to Red – Rossland's backyard. That's a prize worth more than $1,200!

Named for the club that made up part of the famed Rossland Ladies’ Hockey Team, which you can read about in our story here, The Crescent is a 102-unit residential building located just over 100 steps from the Silverlode chair. To enter, simply register to learn more information about The Crescent on their website: thecrescentatred.com. (Click the image below to take you there.)

Sorry kids, but you have to be 18 years old to enter.

Contest ends January 22, 2022.

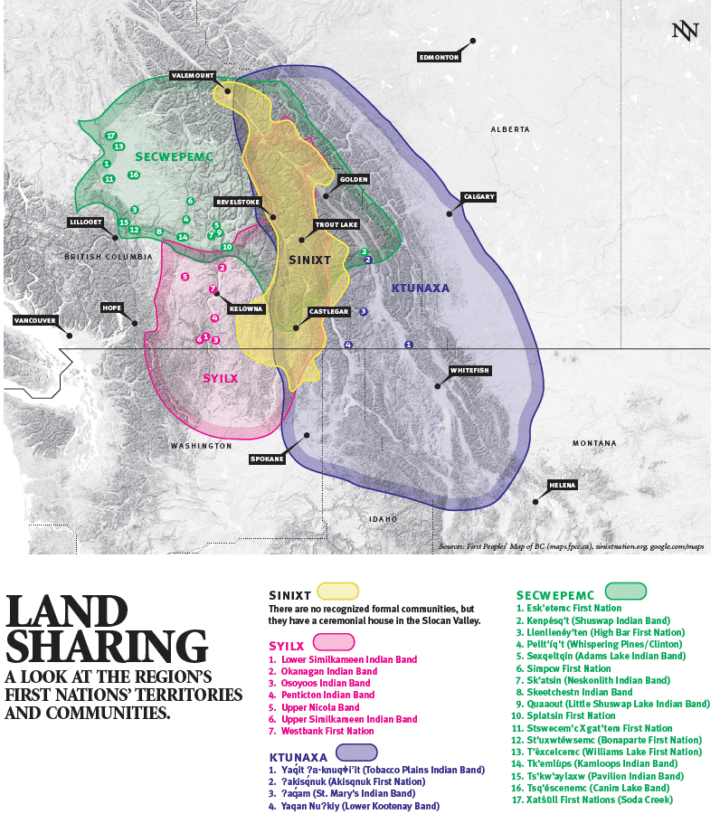

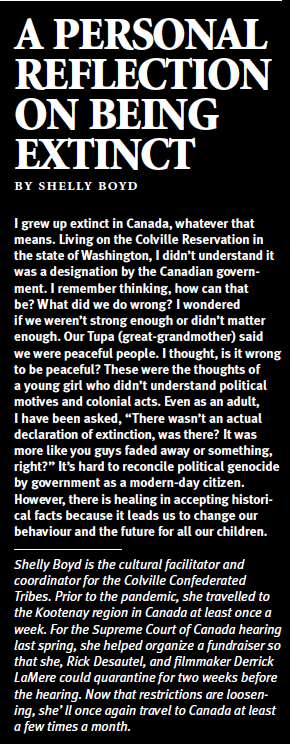

The Saga of the “Extinct” Sinixt

In 1956, the Sinixt people were declared extinct by the Canadian government. After an 11-year legal battle, the Supreme Court of Canada has ruled the Sinixt should now have access to their traditional hunting territory, which encompasses a large swath of the West Kootenay region. What does this mean for their “extinct” status and their future? By Bob Keating

Editor's Note: This story first appeared in our winter 2021/22 issue of Kootenay Mountain Culture Magazine and we received some feedback asking why we didn't interview Sinixt members currently residing in Canada. This story is specifically about the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation in Washington and its decade-long legal battle. It's a significant piece of a much larger overarching Sinixt story that will have ramifications for all First Nations with traditional territories that straddle the Canadian-American border.