In an ode to the unkempt and disdained, writer Steve Threndyle dives into one of the most commonly used descriptives in mountain circles. We suggest you read this, dirtbags.

“Threndyle, you ol’ dirtbag, how ya doing?” This is the standard greeting Ean Jackson regales me with when he pops up in my caller ID. Jackson, the nefarious North Vancouver ultrarunner behind the wildly anarchistic Bagger Challenge peak-bagging event, is a good dude. Doesn’t take things seriously. So, why am I rankled when he calls me a dirtbag, a term he’s more than happy to be labelled with?

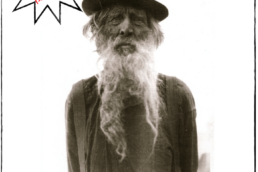

Perhaps it’s the Google definition of, “A very unkempt or unpleasant person.” Unkempt, maybe. But unpleasant? In mountain culture, dirtbags—while not always contenders to date your sister—are always worthy of the same respect as anyone else. One of the toughest skiers I know of on the Coast Range camped in the bush at UBC while completing a doctorate. Some dirtbags I’ve met are rather tiresome, especially once they drone on about obscure land-use access issues.

More recently, climber, podcaster, and parent Fitz Cahall has given voice to the itinerant iconoclasts of the climbing world through his Dirtbag Diaries podcast. He says, “In the beginning, dirtbags were definitely on the fringe and likely had some unsavoury habits, like stealing food off tourist’s plates or dumpster diving. But as I’ve seen the outdoor community grow, I feel like there’s a lot more room, more space, for what it means to people. Which to me is about setting my life’s priorities and do[ing] things that I really care about. And of course, the world is so much smaller thanks to inexpensive travel and social media that, like many things, its meaning has mutated over time.”

The first media reference to the word dirtbag is from the mid-1970s, when actress Claudine Longet was on trial for the murder of Spider Sabich in Aspen, Colorado. A handsome (definitely not unkempt) professional ski racer, Sabich was a big star on the fledgling world professional skiing circuit. He pulled in over $200,000 a year and hung around with Aspen’s beautiful ruling class. As reported in the Mansfield News-Journal, Sabich frequently told friends, “I’m just a dirtbag. Who am I trying to fool?” Longet abhorred the term.

One day, Sabich was showering at Longet’s opulent mansion—dirtbags need showers too—when a gun went off in the bathroom, killing him instantly. A distraught Longet called the Aspen cops. She maintained it was an accident. I have my own theory: they got into an argument and Sabich called her a dirtbag, so she shot him.

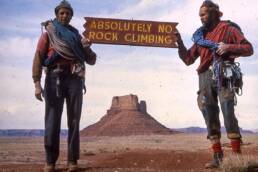

In Valley Uprising, a documentary about the early days of Yosemite rock climbing, Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard gleefully says, “of course, we were all dirtbags,” referring to a band of pioneering rock climbers in the Yosemite Valley in the early 1960s. Yet there’s scant evidence that they used the actual term. “There’s a guy named Mikey Schaefer,” says Chouinard, “a climber who has been in the valley for so long that he’s known as the unofficial mayor of Yosemite. He would never refer to himself as a dirtbag.”

The death knell for a phrase or slogan (think extreme in the 1990s) takes place when someone tries to make money from it. Last summer, I spied a sweet Prana organic cotton T-shirt in khaki green at Mountain Equipment Coop in North Vancouver. The first shock came when I flipped it around to find the slogan, “Embrace your inner dirtbag.” The second shock was that it cost $45. I reflexively flinched, as if I’d just found a mouldy sandwich in the bottom of my backpack.

The first media reference to the word dirtbag is from the mid-1970s, when actress Claudine Longet was on trial for the murder of Spider Sabich in Aspen, Colorado

A couple of months later, I attended a nicely catered fundraiser in Whistler, British Columbia, for the Spearhead Huts project. A friend asked me if I was staying in town for the night, and I said, “Naw, I’m heading back to the city.” He glanced over at the buffet table, where slabs of perfectly sliced roast beef lay uneaten. “You should grab a snack for the ride home or for lunch tomorrow,” he said. “What,” I laughed. “Do I look like some kind of dirtbag?”

I sidled over and chatted briefly with the chef who had carved the meat. “Go ahead, take whatever you want. Here, I can get you a container.”

My friend was grinning as I returned. I had to think fast. “Don’t worry,” I told him. “True dirtbags don’t ask. They just take.” And it definitely doesn’t count if Jackson didn’t see it.

Related Stories

VIMFF

This is the introduction to the 2012 Vancouver International Mountain Film Festival. With films about mountain culture…

“This idea of safety is bullshit anyway.” – Will Gadd

The always adventurous Will Gadd just launched this cool little video about his lifestyle for the Banff Mountain Film…

Framed in Leavenworth With Coast Mountain Culture

This past weekend, CMC was on hand to sponsor and participate in Leavenworth's Framed Photographer Invitational, where…

Coast Mountain Culture Launches Premiere Issue

You may have seen a copy of the new Coast Mountain Culture Magazine (CMC) floating through outdoor veins throughout…