A new documentary chronicles the love, uncertain liberty and all-American pursuit of happiness that found its way to the remote Canadian West Coast over half a century ago. By Megan Cole.

“The Pacific Northwest attracted visionaries and schemers from around the world,” writes Andrew Scott in The Promise of Paradise: Utopian Communities in B.C. “Those who would not remain satisfied with the familiar routine frequently ended up in B.C. Those who were used to moving on and starting anew stopped here as they searched for the kingdom of their dreams – and found they could move no further. British Columbia was the end of the road.” Found at the literal end of the Sunshine Coast Highway on British Columbia’s southwestern coast, the town of Lund could very well be the place Scott was writing about.

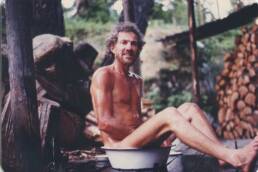

Established in 1889 by two brothers from Sweden, Frederick and Charles Thulin, the community has long held appeal for those seeking a remote way of life. In the Summer of Love, 1967, Peter Behr set out for a new experience, crossing the United States with his thumb out. Behr grew up in New York and was a student at Columbia University. Despite growing up in one of the biggest metropolises in the world, Behr says he’d always been drawn to nature and the outdoors. After spending the summer between his junior and sophomore years travelling across the United States, he decided to try the same thing the following summer, but in Canada.

Behr and a fellow student had read an article in the Georgia Straight by Oscar Green, whom Behr describes as being a hippie real estate agent. Green told readers about the bounty of cheap land available in Lund. Mirroring those who joined the communes that had emerged in the United States and up the coast of British Columbia, many of those who were coming up to Lund bought land together. “It wasn’t a movement,” says Tai Uhlmann, who grew up there and is the producer and director of The End of the Road, a documentary about Lund. “Some people were looking for land. Dad was doing his residency and arrived in Lund and decided to become a dogfish fisherman. They threw away whatever they thought their trajectory was to start something new.”

For the most part, the new Lund residents were young academics, who, despite being brilliant in their fields, were now faced with tasks like building houses, gardening, canning and surviving far beyond what they were accustomed to. “They struggled,” says Uhlmann. “Many locals thought they were just hippies smoking dope, but it was hard if you didn’t know how to do it.”Over time, by learning from each other and from the locals, many of those who’d found themselves at the end of the road were starting to learn the skills they needed to get by. “We did learn how to eat and cook with wood,” says Steven Marx who made the move with his wife, Janet. “We learned preserving and canning, and we raised a lot of vegetables that we’d trade for fish.” Steven learned to love his chainsaw, but as far as other equipment, he says he never became comfortable with it. “I never even learned to repair my car,” he says. “There were strong limitations on our adaptation to really surviving and homesteading, even though we tried very hard for many years.”

In the makeshift homes surrounded by organic gardens, many of the newcomers found the utopia they’d been searching for, but for those like Janet, who were interested in their career and had more experience with academia than butchering, the adjustment to the way of life was challenging. The learning curve was steep, but the community that began to emerge was likely what helped many survive. Women would work together to harvest and process the yields of their gardens, and men spent days chopping and splitting wood. “It was a very strong community,” says Behr. “We helped each other a lot. We had left our families, and it’s not like it is now where you get on your cell phone, but back then long distance calls were very expensive and many people had alienated their parents by leaving. We really were family, a lot of the people. It was a community the likes of which I didn’t recognize at the time.”

Many of those who came up to Lund during the 60s ended up staying and raising children, and some of those children, like Uhlmann, are doing the same. But the remoteness and isolation of life in Lund was challenging for others. The Marxes and their children eventually returned to the States in 1979. Steven wanted to finish the dissertation he’d started as a graduate student, and Janet wanted to offer her children more than Lund and Powell River could offer. Even though it’s been nearly four decades since they left, the Marxes still return to the area every summer.

Related Stories

Eight Minutes in British Columbia

Check out this epic re-edited segment of James Heim shredding BC mountains from Matchstick Productions. Quality action…

Take a Tour of the Cannabis Innovation Centre in Comox, British Columbia

Since legalization in 2018, Canada’s cannabis industry has predictably grown at a healthy rate. As the number of…

Ensnared – The Modern Day Fur Trade in British Columbia

We live in a country that was built upon the fur trade. And even though it no longer retains the same commercial…

Everything You Need To Know About Logging In British Columbia

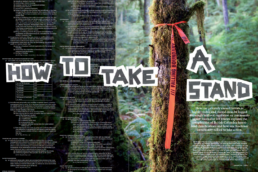

How can privately owned forests in highly visible and visited areas be logged seemingly without regulation or community…