The recently released Lost Kootenays book provides a glimpse back at a simpler time in the region, when things were more black and white. By Greg Nesteroff

How do you choose 130 pictures from among thousands of fascinating images to create a photographic history of the Kootenays? This past year, Eric Brighton and I faced this daunting task when MacIntyre Purcell Publishing asked us to create a companion book to the popular Lost Kootenays Facebook site, which now has more than 50,000 followers.

We started by establishing some criteria. Since the book was to be black and white, we decided to cut things off in the 1950s, before colour photography became popular. Plus, we’d stick to only the best-quality photos. Grainy, blurry, or otherwise less-than-optimal images would be avoided. We also wanted to represent as many communities as possible: larger places might have several pictures each, but we were committed to featuring smaller locales too. Photos depicting people were preferred, particularly those under-represented in local history books, such as First Nations, Chinese Canadians, Indo Canadians, and women. We wanted pictures that have rarely, if ever, been reproduced. While some images in this book have been published before, most have not. Finally, we needed photographs that were affordable. We bought a few from the BC Archives, but at $70 per image, we used them as a last resort. In the end, we had surprisingly few disagreements; it was more like mutual agonizing over which images to cut. We could easily create several more volumes with the images we left out.

Above photo: Employees of the Crows Nest Pass Lumber Company (CNP) take a break to pose for an unknown photographer while working on a massive log jam on the East Kootenay’s Bull River, sometime between 1910 and 1914. In those days, rivers across the province were used as arteries to transport poles to mills, and many loggers were killed doing the dangerous work of clearing jams, such as this one. CNP was founded in 1902 by Scottish immigrant John Breckenridge and a few other business partners. It was based in the community of Wardner on Kootenay River, just south of the mouth of the Bull River, and was dissolved in 1957. Photo: City of Vancouver Archives. Top photo: Fernie, BC, suffered two destructive fires. The 1904 fire, seen here, levelled much of the town. Disaster struck again four years later when sudden winds caused a small forest fire to burn out of control. Within an hour and a half, most of the community had been destroyed and thousands were homeless. At least nine people died and damage was estimated at $5 million (roughly $184 million today). Photographer unknown/Royal BC Museum and Archives

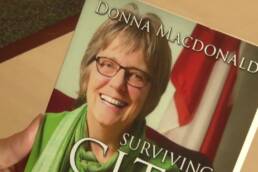

In 1905, the Kootenay Shingle Company of Salmo, BC, hired a number of Chinese-Canadian and Japanese-Canadian employees from the Lower Mainland. Their arrival by train sparked a near-riot by white settlers who felt threatened by labourers working for lower wages. The police had to intervene. Once the initial controversy died down, Japanese-Canadians worked in the woods around Salmo until the start of their internment in 1942. Photo circa 1910. Photographer unknown/Salmo Museum archives.

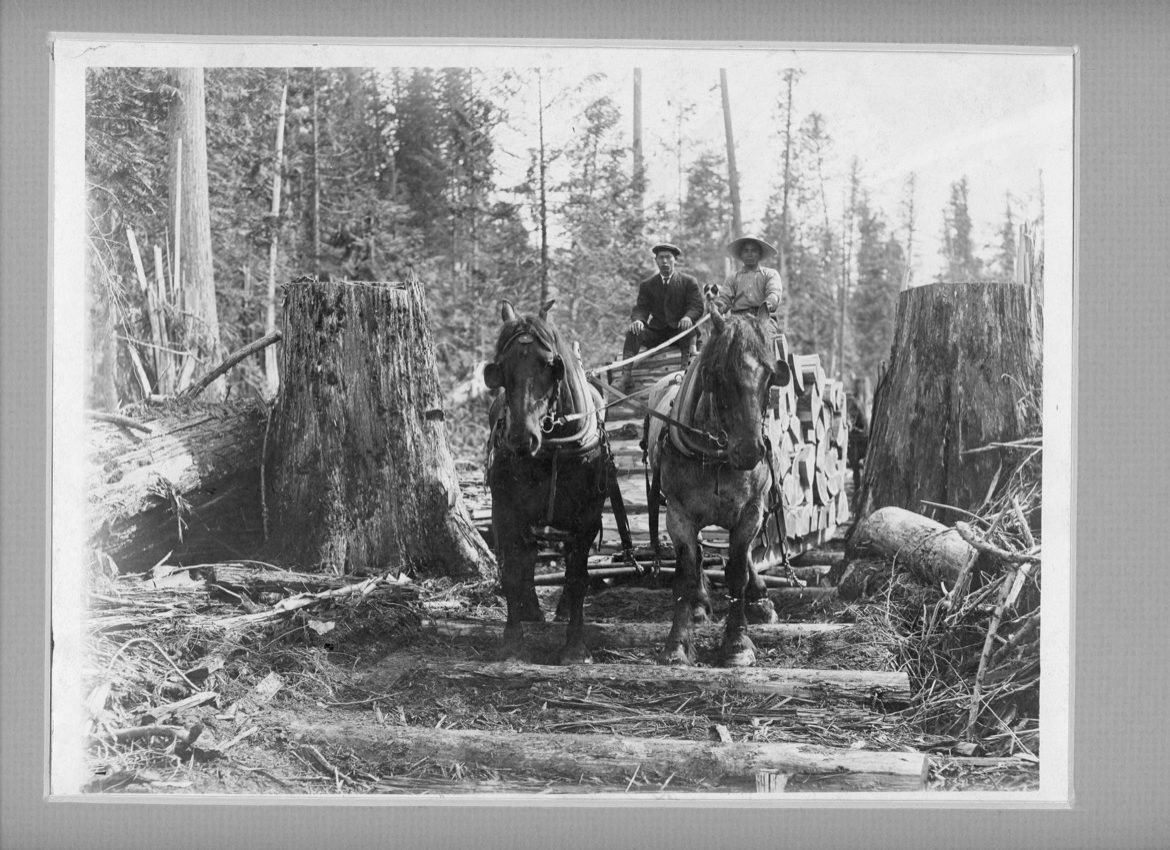

Taken in the 1940s, this photograph shows Doukhobors gathering for moleniye (prayer service) in Castlegar, BC, at the Belyi Dom, a meeting house built in 1911. The name translates to “white house,” referring to the building’s whitewashed exterior. It was demolished in 1949 during construction of the Castlegar airport. Photographer unknown/Greg Nesteroff collection

This photo came with the description “Ed. Young Chef and others playing musical instruments” and was taken in Galloway, East Kootenay, BC, between 1910 and 1914. Photographer unknown/City of Vancouver Archives

This photo turned up on eBay in 2018 and shows three tipis near the CPR wharf in Nelson, BC, circa 1892–93. The SS Nelson is in the background. Photo: Neelands Brothers/Douglas Jones collection

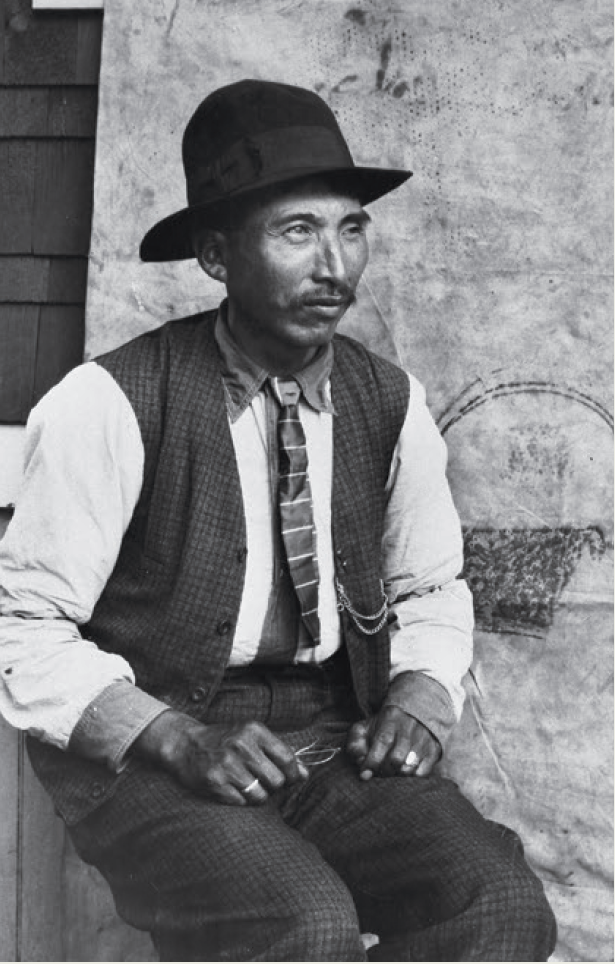

Alex Christian, also known as Pic Ah Kelowna or White Grizzly, was a noted hunter, fisher, guide, and a member of the last Sinixt family to live at kp’itl’els, at the confluence of the Kootenay and Columbia rivers. The purchase of land at that confluence by Doukhobor immigrants displaced the Christian family from their home, and their burial grounds were eventually plowed over by Doukhobor farmers. In 2009, Doukhobor leader J.J. Verigin publicly apologized to Christian’s grandson, Lawney Reyes. Photo: James Alexander Teit/Canadian Museum of History

The Canadian Pacific Railroad’s Pacific Express, Kicking Horse Canyon, near Golden, BC, circa 1890s. Photo: Norman Caple/City of Vancouver Archives

Sourdough Alley in Rossland, BC, 1895. This haphazard business district ran between Washington Street and what is now Esling Park, and a variety of stores did business while squatting on a railway land grant. The street was done away with after Rossland incorporated in 1897. Sourdough was a staple of a prospector’s diet, and the term “sourdough” came to mean an experienced prospector. Photo: Edwards Bros./City of Vancouver Archives

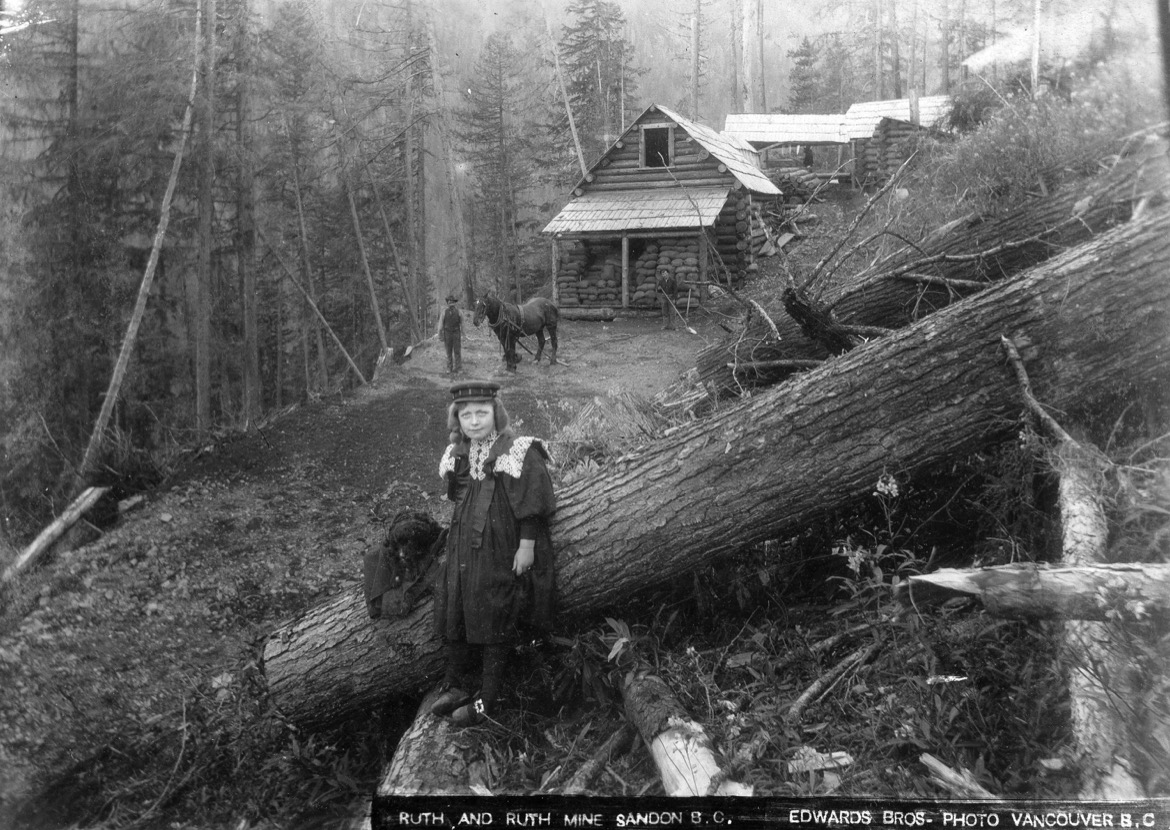

Ruth Mine, near Sandon, BC, 1890s. Is this girl the namesake of the mine? F.P. O’Neill located the claim in 1892 and combined it with three adjacent claims including the Hope, Wyoming, and Ruth Fraction. It was worked profitably for many years, yielding about 776 metric tonnes of silver, 10,000 tonnes of lead, and 1,600 tonnes of zinc. Some of the Ruth Mine’s abandoned buildings are still visible from Sandon. Photo: Edwards Bros./City of Vancouver Archives

Related Stories

Brian Goldstone Coldsmoke Photos

2010 brought blue skies and sun for the 4th annual Coldsmoke Powder Fest, held at Whitewater in Nelson, BC. Highlights…

Book Review: One Foot In

In this book of poems, Jeff Pew explores life’s mysteries—loss, celebration, mindfulness—through the intimate minutiae…

Book Review: Surviving City Hall

In the 1980s, Nelson, British Columbia, was in a depression after its lumber mill and university closed. Now, it’s a…

Book of the mountains – Trailer

"The Book of Mountains 3D" - a new film about skiing from Action Brothers, now in 3D! The film stars Ivan Oleynik, Ivan…

Our Favourite Cedar Shaker Cyclocross Photos

The Cedar Shaker Cyclocross race at Revelstoke Mountain Resort returned for its fifth year last weekend. These are our…

Take Part in the Smart Kootenays Challenge

Columbia Basin communities are looking for your input on how to make the region’s coveted lifestyles even more…