On August 6, 2019, the British Columbia Court of Appeal ruled Jumbo Glacier Resort no longer has a valid environmental certificate and development cannot go ahead until re-assessed.

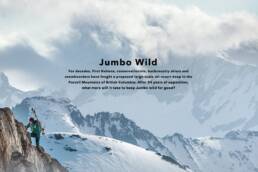

Conservationists are celebrating the latest ruling in the battle of Jumbo Valley in the Purcell Mountains of British Columbia. The BC Court of Appeal recently ruled that the 2015 decision of the Provincial Minister of Environment—that the project’s environmental assessment certificate was expired because the project had not been “substantially started”—should be reinstated after being previously overturned by a lower court.

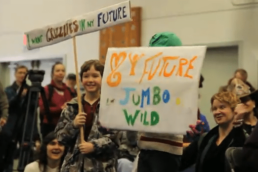

The non-profit conservation organization Wildsight and the Jumbo Creek Conservation Society consider the ruling a big win for Jumbo Valley, which is the sacred area of Qat’muk to the Ktunaxa Nation and an important habitat for grizzly bears. “[We] have spent decades fighting to keep Jumbo Wild,” said Meredith Hamstead of the Jumbo Creek Conservation Society. “We are thrilled that the court has come to the logical decision that the project was never substantially started and its environmental assessment certificate has expired.”

“With the resort dead in the water, Jumbo is going to stay wild. Now, it’s time for Qat’muk to be legally recognized,” said John Bergenske, Wildsight’s Conservation Director, “and beyond Qat’muk, wildlife need long-term protection in the broader Central Purcell Mountains, all the way from the Purcell Wilderness Conservancy to Glacier National Park.”

Since 2014, Ecojustice has represented Wildsight and the Jumbo Creek Conservation Society in the proceedings before the Minister and, along with the Ktunaxa Nation Council, made submissions that formed the basis for the Minister’s decision. “It stands to reason that developers can’t be allowed to hang on to an Environmental Certificate forever. The original assessment for this project was conducted in the 1990s, and was based on information which is now outdated. The law in B.C. requires project proponents to start their projects within ten years of receiving their certificates to ensure that up to date information and the best technology is used to avoid the harmful impacts of large projects like these,” said Ecojustice lawyer Olivia French.

Jumbo Valley is a sacred and spiritual place for the Ktunaxa people known as Qat’muk. It is also part of one of North America’s most important international wildlife corridors and recent research reinforces the importance of this area as grizzly bear habitat and connectivity.

The proposed resort’s environmental certificate expired ten years after it was first granted because by then the project’s developer had only managed to pour a pair of concrete slabs in the remote mountain valley. At issue in the appeal was whether the Ministers’ determination was reasonable that those concrete slabs did not constitute a “substantial start” to the proposed billion dollar resort, planned to include thousands of bed units and numerous lifts.

This is an important win for the Jumbo Valley and was only possible due to a persistent, collaborative effort of more than two decades by many organizations and individuals passionate about protecting this special place.

For more about the Jumbo Resort controversy, read our article, “Jumbo Gets The Go Ahead.”

Related Stories

Keep Jumbo Wild

No, it hasn't gone away quietly into that good night. The proposed Jumbo ski resort is still trying to work its way…

Sherpas Win Big at Banff

Sherpas Cinema, the producers of the newly produced enviro-ski movie All.I.Can have just won a huge award at the Banff…

Jumbo Gets the Go Ahead by BC Government

It's been a point of debate in the Kootenays for nearly 20 years. Today it looks like Jumbo Glacier Mountain Resort is…

Jumbo Wild by Sweetgrass Productions: Trailer and Screenings

Coming to theatres Oct 2015 - Patagonia presents Jumbo Wild – a gripping, hour-long documentary film by Sweetgrass…

HH Big Mountain Battle – Fernie

Helly Hansen's Big Mountain Battle Series just wound up it's Revelstoke Mountain Resort stop, here's a look at the comp…

Win This Rad Power Bikes Electric Bicycle!

There's something about biking in the fresh summer air. The wind on your face. The sounds of passerby. The fact you're…