There sure is, bud. But thanks to its nose for toxins and consumer-protection laws, a sophisticated Oregon lab is helping legitimize the state’s cannabis industry in ways not seen anywhere else in North America. Washington, Colorado, and Canada take note: Green Leaf Lab’s standard-setting impact on pot might light up the whole joint. Story by Geoffrey Nilson.

Since 2016, Oregon has been considered one of the safest places in the world to buy cannabis products. While Colorado was the first state to legalize cannabis for the recreational market, it did so with no testing for pesticides. The problem was that pesticides, which are used in the typical life cycle of agricultural food products, are much worse when burned and inhaled than when ingested orally. People got sick. There were products with very high levels of toxic pesticides. There were lawsuits.

Conversely, Oregon’s cannabis legislation is clear, detailed, and specific. Every new product must be tested for a battery of different pesticides and other harmful substances before it can be offered for sale. The onus is on farmers and producers to have their products tested before they are sold to dispensaries. Test results are logged in a state-wide tracking system. Anything sold to a dispensary or retail shop must be accompanied by documentation confirming test results. “We learned from the mistakes of Colorado,” says Eric Wendt, chief scientific officer of Portland-based Green Leaf Lab. “We learned from the mistakes of Massachusetts. We really learned from the mistakes of Washington.” Wendt’s tone conveys more than regional rivalry. An outsider’s image of the legal cannabis industry can easily be misconstrued: the former drug dealer gone straight, or the stunted intelligence on display in stoner comedies like Pineapple Express. Whatever conceptions you have, Wendt confounds them.

A young professional chemist with an athlete’s build, Wendt comes from a background in pharmaceutical research and development, where he brought a drug to market for pulmonary hypertension. He moved out West from Wisconsin for the mountain biking and rock climbing, even spending a winter between jobs as a ski bum. After some time working in the wine industry and a stint expanding the quality-assurance laboratory of a major nutritional supplement manufacturer, he landed at Green Leaf Lab in 2015.

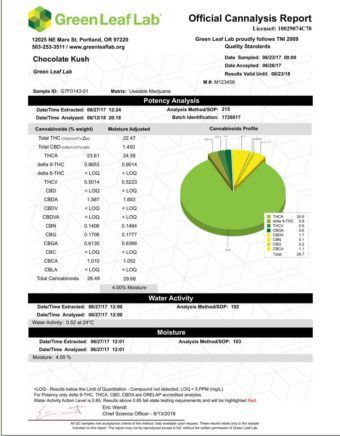

Green Leaf is staffed by professional chemists using scientific instrumentation in an expert lab with sophisticated procedures, hoping, as their website’s mission statement says, to “further legitimize medical and recreational cannabis by imparting knowledge through testing, education, and information.” Every sample to be tested is collected at the site of production by an employee of the lab, a procedure very different than other industries. In addition to all the laboratory testing and on-site sampling, Green Leaf acts as a hub for information; its website is loaded with links about legislation and articles about accurate dosages of edibles.

Green Leaf CEO and owner Rowshan Reordan opened the lab in 2011 with only two staff members, offering testing services to the medical cannabis market. Oregon voted to legalize recreational cannabis in 2015, and with new farmers and producers in need of product testing, the company flourished, becoming Oregon’s first Oregon Environmental Laboratory Accreditation Program-accredited and the first Oregon Liquor Control Commission (OLCC)-licensed cannabis lab. The lab tests for all manner of potentially harmful chemicals, including mould, residual solvents, and 59 different active ingredients in pesticides, as well as for the potency and homogeneity of edibles and extractions.

An ambitious success story in the heat of a boom-and-bust industry, Green Leaf Labs is ranked among the top cannabis businesses in the United States by Cannabis Business Executive. Wendt hopes to change the industry stigma and notes the lab is set up the same as any other food- and drug-testing facility. He understands the complications of cannabis moving from an illegal black market to a legal open market. “It bridges the gap between medicine and something recreational.… and the quality of the product goes a long way toward the acceptance of the industry as a whole.” This proactive approach is not limited to Green Leaf; Oregon farmers, producers, laboratories, and policymakers have all heeded the mistakes of other states, leading to strict policy and a low rate of recall on Oregon products. Wendt remembers “only a few times early on, but declining in numbers since then.”

He concedes the ambiguity written into cannabis policy in Washington and other states could lead to problems, emphasizing why it is so important the legislation gets it right. “Interpretations are crucial,” he explains. “The more you can get into the minutiae and the details, the less ambiguity there will be. The bureaucratic rule writing is hard because every rule means a change in competitive advantage.”

Currently, there are nearly 2,000 different recreational cannabis licenses currently active in Oregon. The actual number of businesses is a harder to ascertain, as some larger companies hold multiple licenses for producer, processor, and wholesaler. The number of retail locations stands at 560, according to June 2018 reports from the OLCC.

The industry by the numbers adds up quick, with nearly 2,000 different recreational cannabis licenses currently active in Oregon.

The state of Washington has over 2,500 active recreational cannabis licenses and 457 retail locations, but as of April 2018, there is still no mandatory pesticide testing for cannabis products, in spite of urgent calls for pesticide policy by industry groups such as the CannaBusiness Association and Cannabis Alliance. The state does mandate testing for potency, water activity, and microorganisms like mould and fungus, but currently the Washington State Liquor and Cannabis Board has no plans to implement mandatory pesticide testing. There seems to be a standoff between businesses that see product safety as crucial to the long-term success of the industry, and those that see regulation as an economic obstacle.

Oregon, by contrast, has got the message that collaboration with industry allows the best development and implementation of cannabis policy. The state’s Rules Advisory Committee revisits legislation every two years (at a minimum, but usually more frequently), and since legalization, it has made regular changes to state cannabis policy based on information from the market and other jurisdictions. Balance is needed between public safety and the interests of the market, and the state government has worked toward the long-term health of the industry through firm and informed policy framework.

Wendt relishes his chance to participate in government teams and focus groups, sitting recently for the state Sub-Committee for Sampling Protocol, helping determine best practices for the industry, and hoping to identify efficiencies in the testing supply chain. “Cannabis turnaround is crucial,” he says, “both because of stability of the product with regard to shelf life, and because of the cost of real estate for storage. Any reduction in turnaround times means the sooner our customers get their products to sale.”

With further normalization of the industry, Wendt expects the future to include inter-state trade, both as an economic boon for superior producers like Oregon and California and as incentive against diversion, the practice of moving legal cannabis into the illegal trade because of surplus. He hopes progress is made around banking for cannabis businesses, highlighting their need to run traditional transaction-based models so they can ditch their reliance on cash. “The idea of recruiting talent is almost impossible because you can’t even talk about offering a 401K,” he says.

The state of Washington has over 2,500 active recreational cannabis licenses and 457 retail locations, but as of April 2018, there is still no mandatory pesticide testing for cannabis products.

Oregon’s industry is contracting from oversaturation, but so far has been free from the torrent of consolidation faced in Colorado in the wake of product recalls. But Wendt is confident the region known for innovation can both “capitalize on an opportunity, but also set an example on how to do it right for entrepreneurs, for the public, and for government regulators.” The story of cannabis in the Pacific Northwest is about the success of small businesses like Green Leaf Lab — companies whose energy and positivity, like Eric Wendt’s, are natural and infectious as they reach for the future while they make it.

Geoffrey Nilson is a New Westminster, British Columbia-based poet and editor who enjoys exploring the weird, wonderful and wicked in his writing.

Related Stories

Mike Hopkins’ Wicked Website

Rossland-based dual-action freerider Mike Hopkins has a spanking website/blog. Check out one of the Kootenays more…

New “Grow Show” Exhibit at Touchstones Museum Celebrates All Things Weed

Touchstone Museum in Nelson, British Columbia has opened its latest exhibit called "The Grow Show" about cannabis…

Does Black Rock Offer The Best MTB Riding in Oregon?

This trail system has been in the works for over 25 years. How the Oregonian rippers of Black Rock built a remarkable…

Take a Tour of the Cannabis Innovation Centre in Comox, British Columbia

Since legalization in 2018, Canada’s cannabis industry has predictably grown at a healthy rate. As the number of…

New KMC and CMC Cover Tease

These are the magazines you will be looking for! They will start to see the light of beautiful day May 16th. Our…