Do you belong here? A researcher and guide asks whether she’s a gatekeeper of the mountains. By Rachel Reimer.

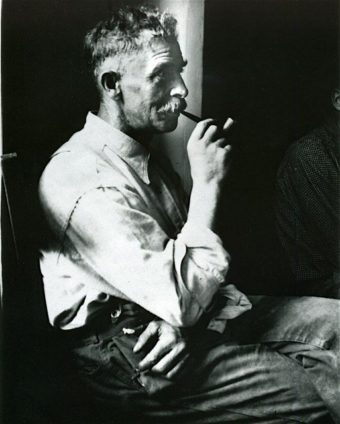

IN THE SUMMERTIME, the Bugaboos, a mountain range in British Columbia’s Purcell Mountains, are a focal point of Canadian alpine climbing. Their spires became legend through climbing pioneer Conrad Kain, who was born in Austria in 1883 to a poor family, enduring a childhood he described as “a miserable existence.” He later became known for his feats of strength in the Canadian mountains at the turn of the century.[1] Yet Kain was not a “bravado mountaineer” like his contemporaries. Rather, he was known for his social tolerance.[2]

Each year I head into the Bugaboos with a group of youth not too different from what I imagine the young Kain was like. I am the co-founder of a Revelstoke, British Columbia-based non-profit called Open Mountains Project, which promotes inclusion in the mountains. We work with a blend of status-quo mountain-town youth and vulnerable youth who experience additional barriers, like fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, gender fluidity, or conflict at home. Alpine climbing is not an easy thing. And yet the task is made more difficult if you believe you don’t belong in the mountains in the first place.

One young person on this year’s trip is Andreas, a 14-year-old who comes from a mountain family and was diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome at a young age. Andreas describes his neurodiversity as autism spectrum disorder (ASD). “It’s not necessarily a bad thing,” he explains. “On the one hand, you can concentrate almost indefinitely on things you love, and so if you love rock climbing, it will become your new purpose in life. But on the other hand, if you’re doing it in a social group and it’s a sport where you need to have good social and communication skills, that can be tricky. If you have ASD, you have a hard time engaging with other people: You can’t make eye contact. You miss social cues that would be obvious to other people.”

The Climb

After dozens of rodents invade our tents and a couple of windy nights that frazzle everyone somewhat, we find ourselves doing some climbing above camp. I urge Andreas to give the pitch another try.

“My toes hurt,” he says. Climbing is hard on the toes.

“You can wear mountaineering boots if you want,” I say.

“I’m not climbing anymore. It’s raining!”

It’s drizzling, but the rock is mostly dry. The night before we talked about mental toughness after watching blinking headlamps in a storm on the northeast ridge of Bugaboo Spire. He bombarded me with questions: Are they okay? Should we call search and rescue? Aren’t they cold? Why would they do that? This led to a conversation about alpine climb-ing, rain, and perseverance.

“You’re not a real alpine climber until you climb in the rain!” I say with a grin, hoping to inspire his second climbing attempt.

He pauses and looks me straight in the eyes. “Are you gatekeeping alpine climbing?”

Ah, shit, I thought. Am I?

According to a 2017 Canadian Avalanche Association study, Canadian mountain guiding professionals and avalanche workers, an industry of approximately 1,800 people, experience six times the national suicide rate.

Belonging

The question of who belongs in the mountains is not new. Mountain culture today is built on a legacy of a specific kind of heroism, a set of stories and beliefs handed down that selectively edit the imaginations of all who participate, so we see only those who are white, hetero, and able-bodied inhabiting mountain spaces. We never question why or how it got to be like this. We tell stories about colonial explorers summiting mountains as if they were the first to do so. But small clues pick at the edges of this Eurocentric narrative, a story told by those who also cast themselves as heroes in it.

The first peak to be summitted in the Selkirk Mountains was likely Avalanche Mountain, by the members of the Rogers family (uncle and nephew), accompanied by a group of (rendered name-less) Shuswap First Nation people on May 28, 1881.[3] Also in the Selkirks sits the Asulkan Range. “Asulkan” is an Indigenous name meaning “wild goat,” and the range stands among peaks in Rogers Pass named for colonizing explorers. To name a place, one must have a relationship with it, one must feel a sense of affinity, belonging, and ownership.

The Hard Question

“You’re not a real alpine climber unless you climb in the rain”: I could add my statement to a long list of well-meaning-but-inappropriate things guides say and move on. But it’s worth sharing my self-reflections here, because, as an advocate for inclusion and an engaged, educated member of the guiding community, if I’m going to react poorly in this situation, then no one is safe.

Option A: Alpine climbing gatekeeps itself. This is where my defensive mind went first. Everyone in the spires that day was climbing in the rain. The weather doesn’t discriminate or care what gender, psychological disposition, diagnosis, or identity you possess. This is the mountain environment in all its pain and glory. I was just stating a fact. The harshness of this place is what keeps some people out. Right?

Option B: I’m the problem, the asshole who’s guarding the gates. My critical self-awareness started to kick in. How did I get to this? My climbing career was marked by nights sleeping on piles of rope; climbing through rain, snow, and injuries; troubleshooting with improvised gear when we forgot shoes, harnesses, or ice axes. Like the Europeans before us, we were heroes in our own stories, regaling each other with epics and near-misses, expect-ing the shaming ridicule. And that ridicule has prompted a constant self-criticism and never-ending treadmill of needing to prove myself, which I’ve done some hard work to unlearn. Still, here I was trying to be inclusive, conscious, kind — and blowing it. I was perpetuating the prove-you’re-worthy-to-belong mentality. Like I had ownership and a duty to initiate others into the cultural legacy wherein only climbers who persevered in the rain deserved to belong.

Option C: Both are true. Is this possible? There are really uncomfortable aspects about being in the mountains: poor weather, avalanches, rockfall, you name it. This discomfort can, and does, keep some people out. And, there is also an added layer of cultural beliefs that build stories and myths that tell us a specific kind of person and certain feats of strength are required to be good enough to truly belong.

Where Does “Prove Yourself” Get Us?

According to a 2017 Canadian Avalanche Association study, Canadian mountain guiding professionals and avalanche workers, an industry of approximately 1,800 people, experience six times the national suicide rate. In Canada’s professional guiding community, 95 per cent of people are white and 85 per cent are male. One in two women experience gender discrimination in the form of being seen as less competent than their male counterparts. One in three experience sexual harassment, 60 per cent of which is from peers. Experiences of discrimination, harassment, and suicide were reported in higher rates for traditionally oppressed peoples. When asked to describe the culture of the profession, guides and avalanche workers most frequently said, “Exclusive.”[4]

What now? Can mountain culture balance its exclusive and competitive aspects with a practice of inclusivity and support? Let’s take Kain, for example. Celebrated mountaineers Hans Gmoser and J. Monroe Thorington described him as respectful, tolerant, and with “qualities of sympathy and patience that made him much loved,” yet he also possessed “the skill, drive and mental fortitude” required to establish immensely challenging climbs.[5] Perhaps we’ve overachieved on cultivating this latter half of Kain’s legacy — that mental toughness, stoicism, and drive that made him so successful in achieving objectives — and yet neglected the tolerance, respect, and humility that made him loved.

The Gnar Belongs to Everyone

In the Bugaboos, I choose to get curious about what gatekeeping means to Andreas. “It’s discriminating, basically,” he tells me, “and I think some people [who feel they are being discriminated against] would work past that and learn about the thing, progress until they get through ‘the gate.’ But some people might be completely dismayed by that, it might break them, and it would be devastating.”

We explore the impact of my words and how to make amends. I let him know that he belongs, and I am proud of him. He doesn’t need to do anything to earn that. In the end, he opts to climb the crack in his mountaineering boots. After three years of climbing with Open Mountains, Andreas believes “just about anyone can climb.”

Sometimes I’m the asshole. But in acknowledging and working through my own culpability, I’m also becoming the kind of climber I hope Conrad Kain would be proud of, one who is willing to lay it all out there in service of an inclusive and kind mountain culture.

Rachel Reimer is a guide, researcher, and advocate for inclusion in mountain culture. She’s executive director of the Open Mountains Project and co-chair of the Association of Canadian Mountain Guides’ diversity and inclusion committee.

NOTES

- 1. Conrad Kain. Where the Clouds Can Go. (Calgary: Rocky Mountain Books, 2009), xix.

- 2. Ibid., xx.

- 3. David P. Jones, Rogers Pass Alpine Guide: The Heart of the Selkirk Range (Squamish: High Col Press, 2012), 142.

- 4. Rachel Reimer. Diversity, Inclusion, and Mental Health in the Avalanche and Guiding Industry

- in Canada. (Canmore: Association of Canadian Mountain Guides, 2019), https://www.acmg.ca/05p df/2019DiversityInclusionandMentalHealthStudyFI NALReport.pdf.

- 5. Conrad Kain. Where the Clouds Can Go. (Calgary: Rocky Mountain Books, 2009), xxii.

Correction

In our latest print issue of Kootenay Mountain Culture Magazine(Winter 2020-21), this story is titled “Do You Belong Here?” and its subhead has an error. We mistakenly refer to the author, Rachel Reimer, as a “mountain guide,” when she does not have Association of Canadian Mountain Guide certification for this title. She is a guide who works in the mountains. We sincerely regret the error.

Related Stories

Framed in Leavenworth With Coast Mountain Culture

This past weekend, CMC was on hand to sponsor and participate in Leavenworth's Framed Photographer Invitational, where…

Coast Mountain Culture Launches Premiere Issue

You may have seen a copy of the new Coast Mountain Culture Magazine (CMC) floating through outdoor veins throughout…

New Summer Issue of Coast Mountain Culture Days Away

It's at the printer getting printed, and we can't wait to drop our first ever summer edition, the Versus Issue. Stay…

The Gathering at Red Mountain

This upcoming Easter weekend RED and POWDER Magazine are presenting the 2nd annual Gathering at RED. Come hang with…

Our New Store – Kootenay Mountain Culture + Coast Mountain Culture

We got tired of people asking for the shirts off our backs and the hats of our noggins. So we opened an online store.…