How is it that a small team of snow pros can generate a comprehensive and critical avalanche forecast about Canada’s mightiest mountains, every single day, all winter long? Like this. By Phil Tomlinson.

Writing an avalanche bulletin requires knowing every layer in the snowpack, what the weather’s been, and what the weather is about to be. Multiply that by 15 regions across Western Canada and you have the largest avalanche-forecasting program by area in the world. From November to early summer, a team at Avalanche Canada disseminates reams of data to create bulletins that help inform those who play in the mountains. Safety is the main goal, and it’s a Sisyphean task: the second a forecast bulletin is posted, the clock resets and the team goes back to square one. Here’s how each avalanche forecast is compiled.

9:00 a.m.

9:00 a.m.

Avalanche Canada’s forecast team is made up of four on-duty forecasters and Ilya Storm, the forecasting program supervisor. Each forecaster is assigned about four regions, and the first task every day is to figure out the previous night’s weather. For their initial information, the forecasters consult weather actuals, a stream of data from weather stations.

9:45 a.m.

The next step is determining what the snowpack has been doing. Guides, heli-ski companies, BC Parks, and lodges and resorts use an online system called InfoEx to share information. It’s a dense stream of shorthand and symbols that allows professionals to share exactly what they’re seeing. It’s a gold mine for the forecasters. However, not every area has enough professionals to give the forecasters the info they need. To fill one gap, Avalanche Canada has a South Rockies field team. The small crew spends its days as eyes and ears: if a forecaster wants to know what’s happening on north-facing ridge tops at 2,000 metres (6,560 feet), the field team gets that data.

10:45 a.m.

10:45 a.m.

The pros aren’t the only source of info. The Mountain Information Network is like the InfoEx for laypeople. For example, someone might upload something as simple as, “Killer day, little slabby near the ridge, but treeline skiing was amazing,” along with a photo and location. Forecasters pore over the photos looking at details like how much snow is sitting on tree branches, how deep skiers are penetrating, and the spindrift off ridge tops, among other clues.

11:30 a.m.

All that info comes together to create the Nowcast. This is the forecasters’ best understanding of what the current situation is in each of their regions. They present their analysis to each other and debate interpretations. Once in agreement, the team feels confident they know the current conditions. Time to predict the future.

1:00 p.m.

Every day the team has a Skype meeting with a professional weather forecaster from Environment Canada’s Meteorological Service of Canada, who shares what the weather models are calling for. Using high-resolution imagery from government satellites, the forecaster starts with a macro view and then works down to specific details region by region.

1:45 p.m.

The forecasters figure out how the incoming weather is going to affect the snowpack. They consult the Nowcast and determine where the wind will drop incoming snow and how the snowpack in those areas will respond. They also take sun, snow, and cornices into consideration.

2:30 p.m.

2:30 p.m.

Once again each forecaster must present the regions he or she is responsible for to the rest of the team and there are discussions and debate. Language is key because a bulletin must be precise and succinct, but if people see the same thing being shared all season long, there’s a danger of message fatigue, and they could stop paying attention.

4:00 p.m.

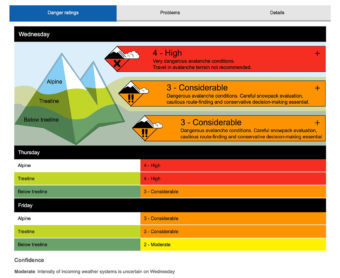

Once everyone agrees, the forecasters finish their bulletins, enter them into the system, and the coming day’s bulletins are live.

Related Stories

Avalanche Awareness Course for Youth

The Avalanche Awareness Beyond the Boundaries Society put on another successful 3 day AST training course at Whitewater…

Snake River Float Avalanche Airbag Save

This avalanche airbag footage was caught on January 25th, 2012 in the Snake River backcountry near Montezuma, Colo. It…

Tree Skiing, The Sweetgrass Way

So many questions...how did they do it? How long did it take? Where was it filmed? The answers will be available next…

Selkirk Wilderness Skiing Sees A Changing of the Guard

Rumour has it that the originators of catskiing, Selkirk Wilderness Skiing, has been sold. We don't have much…

Skiing with Hassan

With rubber boots, berber tunes and an a-okay from allah, one giddy moroccan makes tracks in the atlas range. This man…