Thirty years after the world watched British Columbia’s War in the Woods, Clayoquot Sound is stirring with unrest again. Amid Indigenous People’s struggle to steward the land and the resource sector’s goal to employ, a million annual visitors now stream to this delicate place. By Andrew Findlay.

Joe Martin remembers falling old-growth trees high on steep mountainsides above the Cypre River valley on Vancouver Island, British Columbia, only to watch them explode into infinite pieces when they landed, as though their trunks were packed with dynamite. Some of the trees were alive when Vikings landed at L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland and Labrador a millennium ago. It made Martin feel sick to his stomach.

One day in 1981, Martin was working the valley bottom when he saw juvenile trout and salmon darting among the pools of a clear stream. All around was a scene of logging devastation. He found the sight both pathetic and inspiring. Pathetic because land sacred to the Nuu-chah-nulth people who have inhabited Clayoquot Sound for at least 5,000 years could be reduced to this by a few days of industrial logging. Inspiring because life—even these diminutive flashes of silver and mottled metallic green—could persevere despite the liberties humans take with the planet. Something stirred in Martin’s soul. So, rather than fall an adjacent copse of giant cedars, whose growth was nourished over centuries by the timeless nutrient-rich cycle of dying salmon in the stream, he left it standing. “I felt guilty. My father had been a fisherman all his life,” says Martin, a member of the Tla-o-qui-aht, one of 14 Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations on Vancouver Island.

One day in 1981, Martin was working the valley bottom when he saw juvenile trout and salmon darting among the pools of a clear stream. All around was a scene of logging devastation. He found the sight both pathetic and inspiring. Pathetic because land sacred to the Nuu-chah-nulth people who have inhabited Clayoquot Sound for at least 5,000 years could be reduced to this by a few days of industrial logging. Inspiring because life—even these diminutive flashes of silver and mottled metallic green—could persevere despite the liberties humans take with the planet. Something stirred in Martin’s soul. So, rather than fall an adjacent copse of giant cedars, whose growth was nourished over centuries by the timeless nutrient-rich cycle of dying salmon in the stream, he left it standing. “I felt guilty. My father had been a fisherman all his life,” says Martin, a member of the Tla-o-qui-aht, one of 14 Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations on Vancouver Island.

His refusal to cut these trees cost him a faller’s job with Pat Carson Bulldozing, a major subcontractor to MacMillan Bloedel, which was the granddaddy of British Columbia forest companies. Martin says getting fired was “a weight off my shoulders.” Something had changed. A year later in 1982, he was linked arm in arm with other protesters on the beach at C’isaqi on Meares Island, opposing MacMillan Bloedel’s plan to clear-cut 90 per cent of the island. A journey to reclaim a piece of Martin’s heritage—and the land it was borne from—had begun.

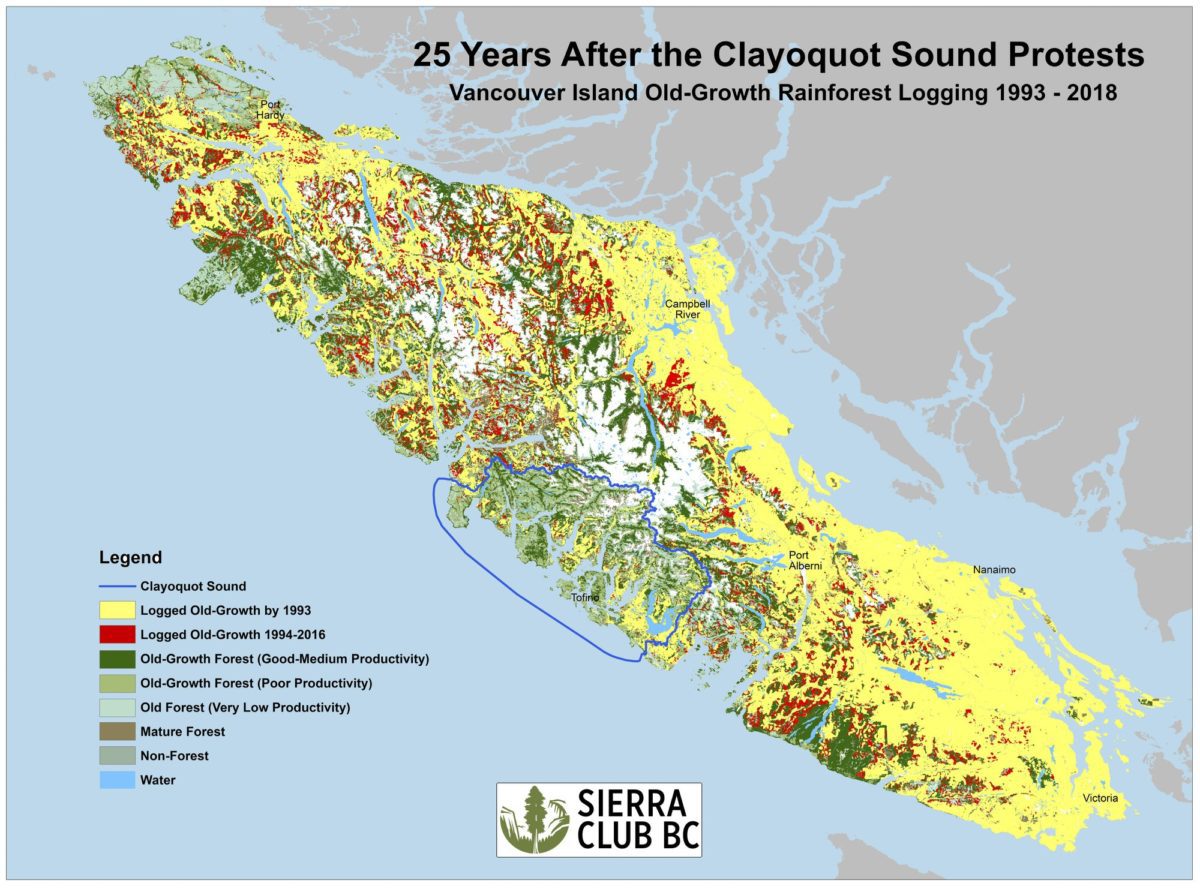

In the 1980s, logging operations were obliterating old-growth. In 1988 alone, nearly one million cubic metres—equal to 29,000 logging truckloads—was felled in Clayoquot Sound. It was a gold rush in the woods of Vancouver Island, and the logging companies were kings. Yet that unquestioned reign was soon to end. In the early 1990s, after the province tried to pass a land-use plan that permitted clear-cut logging in 50 per cent of Clayoquot Sound, a grassroots protest began boiling over. The War in the Woods, as it came to be known, had begun. Australian enviro-rockers Midnight Oil played a benefit concert in the “black hole,” a desolate clear-cut along Highway 4, where protesters, many of whom had never marched or waved a placard in their lives, began camping en masse. American environmental lawyer Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and other high-profile personalities lent their voices to the cause. It helped transform British Columbia’s dirty little old-growth logging secret into an international shame. It would eventually help change the socio-economic landscape of forestry in the province and, more specifically, the relationship between industry, government, and First Nations.

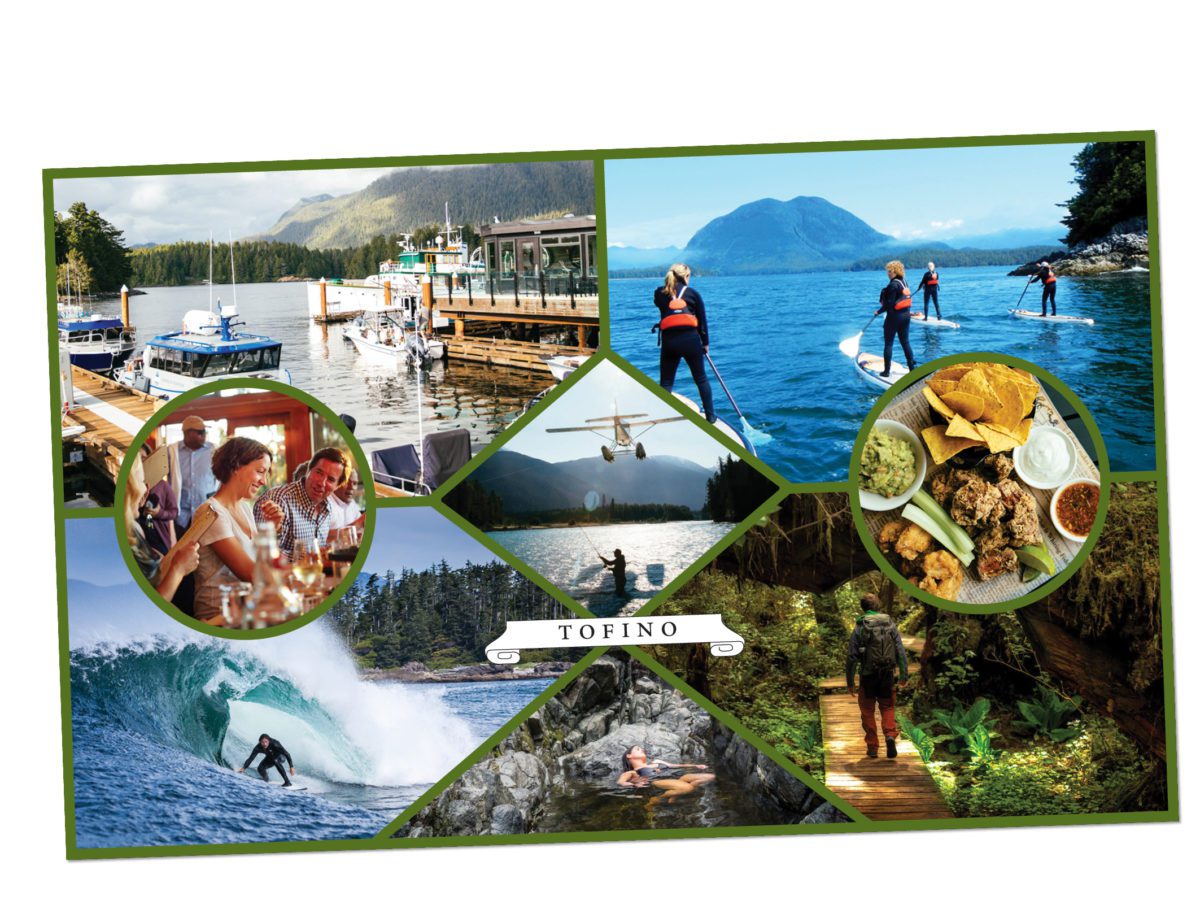

Fast forward 30 years: what does reconciliation look like today for the Tla-o-qui-aht and their neighbouring Clayoquot Sound nations, the Ahousaht, Hesquiaht, Toquaht, and Ucluelet? “We had no idea what tourism would become in Tofino,” Martin tells me, recalling the politically charged protests on Meares Island. “Now they call it the ‘Whistler of the West Coast.’ I have lots of friends who can no longer afford to live here,” he says of the popular village at the southern edge of Clayoquot Sound.

Fast forward 30 years: what does reconciliation look like today for the Tla-o-qui-aht and their neighbouring Clayoquot Sound nations, the Ahousaht, Hesquiaht, Toquaht, and Ucluelet? “We had no idea what tourism would become in Tofino,” Martin tells me, recalling the politically charged protests on Meares Island. “Now they call it the ‘Whistler of the West Coast.’ I have lots of friends who can no longer afford to live here,” he says of the popular village at the southern edge of Clayoquot Sound.

Indeed, monster homes on Chesterman Beach now list for $2.5 million or more, and local housing is in short supply. Therein lies the complexity of Tofino: a tourism industry is striving to manage its growth against the backdrop of First Nations still struggling to reclaim what was theirs. In the decades following the War in the Woods, the growth of tourism in Tofino has been nothing short of remarkable. When Martin laid down his chainsaw in the Cypre Valley, Tofino was a diamond in the rough, a logging and fishing town to the core. Dozens of commercial fishing vessels were tied up at the Tofino dock, and loggers far outnumbered sea-kayak guides.

“We had no idea what tourism would become in Tofino. Now they call it the ‘Whistler of the West Coast.’ I have lots of friends who can no longer afford to live here.” – Joe Martin

Today, roughly one million tourists drive through the Pacific Rim National Park Reserve annually, jostling for parking spots along Tofino’s bursting streets, which retired Parks Canada staffer and long-time resident Bob Hansen calls a “Rubik’s Cube” in summer. Thirty years ago, surfing here was only for hardcores. Today, more than a half-dozen surf rental and instruction companies contribute to a tourism economy that generates $250–$300 million in revenue each year, most of it during a feverish four-month season.

So too does a culinary scene that punches far above its weight nationally. In 2003, when SoBo was still pumping out its legendary fish tacos from a trailer, it was named one of the top-10 new restaurants in Canada by En Route magazine. And in 2014, Wolf in the Fog, the bistro famed for West Coast-inspired cocktails mixed with ingredients like smoked salmon-infused vodka and cedar-infused rye, scored the number-one spot on En Route’s coveted list. Paul Moran, a protégé of Vancouver’s famed David Hawksworth, helms Tofino’s newest high-end restaurant: 1909 Kitchen at the freshly renovated Tofino Resort and Marina.

Sitting on a barstool at The Hatch Waterfront Pub, which is also part of the new resort, tourists can gaze out at emerald green Meares Island, which on a map appears like a crab pincer reaching toward Tofino. Recently, when local tourism business owners were asked what their guests seek when they visit Tofino, the most common answer was spiritual connection. Sitting astride a surfboard off North Chesterman Beach on a winter day, with the sky as incandescent a blue as the inside of an abalone shell, and Sitka spruce towering along the shoreline dusted in snow, it’s hard not to agree—Tofino’s overwhelming sense of calm and beauty is, well, spiritual. Yet, behind the camera-friendly views of Clayoquot Sound lie simmering conservation questions and conundrums.

Sitting on a barstool at The Hatch Waterfront Pub, which is also part of the new resort, tourists can gaze out at emerald green Meares Island, which on a map appears like a crab pincer reaching toward Tofino. Recently, when local tourism business owners were asked what their guests seek when they visit Tofino, the most common answer was spiritual connection. Sitting astride a surfboard off North Chesterman Beach on a winter day, with the sky as incandescent a blue as the inside of an abalone shell, and Sitka spruce towering along the shoreline dusted in snow, it’s hard not to agree—Tofino’s overwhelming sense of calm and beauty is, well, spiritual. Yet, behind the camera-friendly views of Clayoquot Sound lie simmering conservation questions and conundrums.

IN 1995, THE SCIENTIFIC Panel on Sustainable Forest Practices released a report that set guidelines for a lighter touch of logging in the sound, with strict limits and minimums on everything from cutblock size to the amount of old-growth retention. A step forward, no doubt. In 2000, Clayoquot Sound was declared a UNESCO World Biosphere Reserve, joining a network of nearly 700 such reserves in 120 countries. It’s human nature to crave closure, and it would be much too easy to file Clayoquot Sound under victory. There’s no doubt that attaching the UNESCO acronym has brought a level of international profile that would have been otherwise unattainable—the very name “biosphere” implies protection or preservation. But although having the designation has unlocked funding for ecological and cultural research and education, it comes with no regulatory teeth. That’s why for people like Dan Lewis and Bonny Glambeck, former kayak-tour company owners, veterans of many environmental protests and actions, and founders of a small environmental non-governmental organization called Clayoquot Action, the biosphere reserve is largely symbolic, perhaps even misleading. It gives some people the impression that Clayoquot Sound’s environmental battles are over. “A lot of people think that Clayoquot Sound is a closed chapter, but it’s not,” Lewis says, from Clayoquot Action’s shoebox-sized headquarters in a building on Tofino’s Main Street that it shares with an art studio.

Lewis touts the need for what he calls “Clayoquot 2.0,” a reboot of the public engagement that was intensely focused on the sound in the 1990s. Name any Canadian resource industry, and it’s a factor in Clayoquot Sound. Imperial Metals—which was at the helm of one of the worst environmental mining disasters in Canadian history when a tailings dam failed at its Mount Polley Mine near Williams Lake, British Columbia, in 2014—owns minerals rights in both Ahousaht and Tla-o-qui-aht territories. Between Cermaq and Creative Salmon, there are more than 20 Tofino fish-farming tenures. And when the playing field for forestry shifted dramatically in the 1990s, a large portion of logging rights in Clayoquot Sound was granted to First Nations, managed through a then-new company called Iisaak Forest Resources Ltd., which is jointly owned by five nations. But, like any crown logging tenure, the right to log comes with obligations to cut a certain amount of timber annually and pay rent to the government in the form of stumpage fees, meaning ancient forest remains at risk in unprotected valleys of Clayoquot Sound. Even tourism, Tofino’s saviour from the ravages of resource extraction, is facing its own conservation struggles. Like an incoming tide on a shallow sandy shoreline, tourism seemed to roll forward in Tofino, almost imperceptibly at first.

I MEET SAYA MASSO, natural resource manager for the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation, at his corner office in a repurposed ATCO trailer. It is on the same road that leads to the Tin Wis, a Tla-o-qui-aht-owned resort on Mackenzie Beach that, along with several run-of-river hydroelectricity projects and partnerships, is a cornerstone of this nation’s economy. Masso’s office is also next door to a much-needed new housing project being built by the Tla-o-qui-aht using old steel shipping containers.

Sitting astride a surfboard off North Chesterman Beach on a winter day, with the sky as incandescent a blue as the inside of an abalone shell, and Sitka spruce towering along the shoreline dusted in snow, it’s hard not to agree—Tofino’s overwhelming sense of calm and beauty is, well, spiritual.

Masso is Tla-o-qui-aht and was raised in Victoria, British Columbia. After completing a master’s degree in Indigenous governance at the University of Victoria, Masso returned to the “territory” with a profound sense of what it means to be an Indigenous man in the 21st century, and the need to seek justice, reconciliation, and equality for his people on the land they have inhabited since, as the saying goes, time immemorial.

Masso pulls out a map that depicts much of Clayoquot Sound and Esowista Peninsula the way the Tla-o-qui-aht see it. Their traditional territory is divided into four tribal parks: Tranquil, Ha’uukmin (Kennedy Lake watershed), Wah-nah-jus-Hilth-hoo-is (Meares Island), and Esowista (encompassing the town of Tofino.) “It’s our way of saying these lands need to be managed sustainably for clean water, biodiversity, and the future,” he says.

In other words, around here, pretty much every pint raised, beach walked, surfboard rented, bottle of wine uncorked, or whale, bear, or wolf watched occurs on a Tla-o-qui-aht tribal park. Though tribal parks have no legal status in the eyes of the province, they are hugely significant to the Tla-o-qui-hat. “Tourism kind of snuck up on us. The tourism sector never really came to the table the way fish farming and forestry were forced to,” Masso says. “To be honest, I don’t think the average visitor to Tofino realizes that they are setting foot on ancestral lands. Parks Canada has a visitor centre, we don’t have a long house. They have a trail crew and budget to look after facilities, we have myself and another guy with a chainsaw to maintain trails like the Big Tree Trail on Meares Island.”

It’s not as though the Tla-o-qui-aht are silent bystanders. The nation owns and operates Tin Wis Resort, and band members have become cultural ambassadors, like Martin’s daughters Gisele and Tsimka who are both guides and owners at Tla-ook Cultural Adventures and T’ashii Paddle School, respectively. Still, Masso believes the Tla-o-qui-aht have a ways to go before they are full participants in a lucrative tourism sector that trades on the very beauty of their traditional territory.

To be fair, Tofino’s tourism players are hardly lacking a conscience. Dorothy Baert, a third-term Tofino councillor and the owner of Tofino Sea Kayaking, struggled to raise two kids as a single mother in Vancouver before relocating to Tofino in the early 1980s. Early on, she stood alongside Ahousaht and Tla-o-qui-aht protesters and fostered a deep connection to this land and its people. Back then, she says, tourism was fledgling, and women stood out as entrepreneurs. The Pacific Rim National Park Reserve attracted an educated workforce of biologists, ecologists, and other specialists, which made for an interesting and capable community. The raw materials were there for tourism success. “It was an extraordinary place to discover, but I don’t think anybody envisioned the growth that tourism would realize,” Baert tells me.

With growth comes growing pains. For the past three years, she has been vacating her Tofino home in summer to make it available for her staff to rent—that’s how bad the housing situation is in Tofino. It’s so difficult during the peak season that some service workers are forced to live in tents. Baert is acutely aware of the delicate balance between tourism and First Nations. As a town councillor, she has been involved in discussions to formalize a system in which tourism businesses pay a fee to First Nations for the use of traditional territories. It’s a practice Baert initiated voluntarily at Tofino Sea Kayaking (for every guest who visits the Meares Island Tribal Park, the company pays a user fee to the Tla-o-qui-aht.)

So too does Ocean Outfitters. This company specializing in sea kayaking, wildlife viewing, and sport fishing has been around for decades, but in recent years, it has repositioned itself as more social enterprise than for-profit business. It is Tofino’s first carbon-neutral tourism company, and it plows profits back into an array of environmental and conservation issues. For example, the company is working closely with the District of Tofino on developing a Wildlife-Human Hazard Assessment and Management Plan for the town, and its Three Percent for the Fish Initiative adds a three percent surcharge to all of its fishing charters to raise funds for local salmon-enhancement projects. Ocean Outfitters also supports the efforts of Surfrider Pacific Rim, the local chapter of the global surfer-run beach cleanup organization. “It’s a wonderful opportunity,” says Ocean Simone, the Burlington, Ontario-born manager of Ocean Outfitters, about the ability to put support and resources behind conservation efforts that directly impact the region.

Name any Canadian resource industry, and it’s a factor in Clayoquot Sound. Imperial Metals owns minerals rights in both Ahousaht and Tla-o-qui-aht territories. Between Cermaq and Creative Salmon, there are more than 20 Tofino fish-farming tenures. Even tourism, Tofino’s saviour from the ravages of resource extraction, is facing its own conservation struggles.

Simone does admit to some trepidation about the impact that Tofino’s super-heated tourism economy is having. Whether it’s the seaplane and boat traffic or the human habituation of bears and wolves following months of wildlife-viewing excursions, she believes it’s imperative for Tofino’s tourism sector to look in the mirror and examine how it relates to the land and sea—this misty place on the edge of a continent that can move people so profoundly, even spiritually.

On a busy Saturday in June, the parking lot of the Rainforest Trail—a popular one-kilometre-long interpretive walk in Pacific Rim National Park—is packed. A mix of accents and languages rings out: Dutch, German, French. I set off along the trail; it’s dead flat at first where it traverses the site of an old antennae installation that is now slowly being reclaimed by a dull second-growth forest. Soon the smell of fresh-cut cedar becomes strong, and the trail enters primal forest and joins a boardwalk recently rebuilt by Parks Canada staff. Less than two kilometres away, churning surf pounds Wickaninnish Beach, but here the forest is silent, except for the joyous chatter of a Pacific wren. I pause on a bridge and gaze upon a Garden of Eden: luminescent green deer fern sprout from moss, an ancient fallen cedar provides a platform for a string of delicate hemlock seedlings, and salmonberries hang over a crystalline stream where coho fingerlings dart among shaded pools. Outwardly chaotic, the rainforest has an ordered beauty that is a study in perfection. I sense how a young Joe Martin must have been moved to lay down his chainsaw when he looked upon a similar scene so many years ago in a Clayoquot Sound valley sitting precipitously on the verge of destruction.

Andrew Findlay

Andrew Findlay is an award-winning journalist and photographer with a home base on Vancouver Island. Born and raised in British Columbia, he continues to draw inspiration from the people, places, triumphs and travails of the Canadian West, however he ranges across the globe in pursuit of stories. Andrew’s journalistic interests are many; he enjoys peeling back the complex layers of social, environmental and business issues, but is also inspired by travel and outdoor adventure. Magazine and newspaper assignments have taken him to lands and cultures as diverse as the Great Bear Rainforest of BC, the remote mountains of northwestern Guatemala and the frozen ice hockey ponds of northern India.

Related Stories

Golden Sound Festival Recap

Festival season is almost at a close across the Kootenays, but the sweet sounds of summer are still ringing between our…

Golden Sound Festival – August 19 & 20

If you're in the East Kootenays this weekend be sure to check out the Golden Sound Festival, scheduled to go off August…

A Tofino Weekend

This past weekend, the Coast Mountain Culture crew headed to Tofino to take in some sun, surf and all the Monsterous…

Rip Curl Pro Tofino Slideshows

Two weekends ago, the Rip Curl Pro Tofino played host to a slideshow photography competition featuring Kyler Vos, Mason…

Sanuk Canada Wants to Bring you Surfing In Tofino

Get on it, friends... Facebook Use the attached FACEBOOK.jpg image to post in Facebook Use this pre-populated contest…

Sick Pics: Tofino’s 10th Rip Curl Surf Comp

Thirteen-year-old Canadian surfing phenom Mathea Olin slayed it at the Rip Curl Pro Surf Comp in Tofino this past……