Raised high in the glacial backcountry of the Columbia Valley, among the Olympic-calibre race gates of her local hill, Christina Lustenberger is considered one of the foremost big-mountain skiers of her generation. Cassidy Randall chronicles the career of a down-to-earth athlete who lives for more than shredding the edge.

From the helicopter, Christina “Lusti” Lustenberger spots a potential line on Wildcat Peak deep in British Columbia’s Rocky Mountains, just north of Mica Dam. Its hanging face falls off into a rank of cliffs on the left, a monster cornice settles on its right shoulder, and vertical spine walls rise through its centre. It’s a dangerously beautiful feature where a fine line exists between skill and recklessness.

It’s the first day of filming at Mica Heliskiing for an upcoming film project by Sherpas Cinema. As the helicopter banks away in search of friendlier terrain to warm up on, Wildcat sears itself into Lustenberger’s memory. She and fellow pro skier Dane Tudor snap photos of the line and discuss coming back to it if the conditions improve. It’s not for the glory of skiing, or the social media fame of descending such a stunning feature. For Lustenberger, it’s the prospect of reaching her full, considerable potential as a skier, the pursuit of which drives her more than anything else. She calls it “chasing the unicorn,” and this film project has created the perfect hunt.

The film will celebrate the region carved by North America’s largest river, the Columbia, and the same region that raised Lustenberger to be one of the most formidable big-mountain skiers in the world. But unless you already knew about her reputation in the mountains, you’d never glean her lofty status from talking to her. She’d sooner hear about your love life or discuss Revelstoke, British Columbia, city politics than recount her latest first descent. “It’s a highlight of my career to get a call from the Sherpas,” she says from her post by the fire in the luxe Mica Lodge. She is feeding her tea addiction, sipping her third or fourth cup since coming in from filming on day two. When the British Columbia-based film company approached her to be part of the project, she was in before she even heard the specifics. Intended as a wild juxtaposition of industry and ski tourism—with a narrative that ties logging, mining, and dams with skiing legendary mountain ranges—the film will explore the unique characters and culture of the British Columbia interior. “To be part of this project is something that’s close to my own story of evolution in this valley.”

Lustenberger is sponsored by Arc’teryx, Black Crows, Petzl, and Smartwool. She’s known for pushing limits in the backcountry and making first descents. On a 2016 mission in British Columbia’s Waddington Range, her endurance drove fellow Arc’teryx skier Eric Hjorleifson to hide beers in her pack in an effort to slow her down. Most of her first descents are in British Columbia, like her lines down Consternation Chute in the Selkirks and the Blackfriar in the Adamants, a line bisected by a 15-metre vertical wall of ice. Her ski partners rappelled it, she skied it clean. These roots are why Lustenberger keeps using the word “authenticity.” It’s why the Columbia River Project appeals to her. “Otherwise, you’re skiing somewhere across the world with some fabricated connection that a company is trying to make,” she says. “You end up pushed around by someone else’s vision. And what are you doing it for? The glory?”

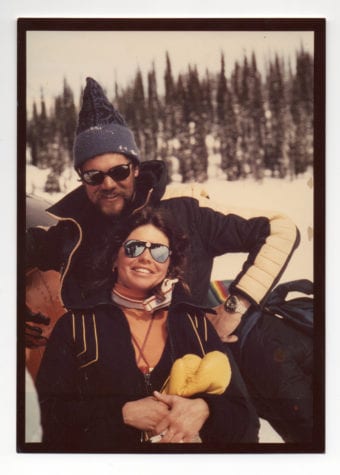

Skiing is built into Lustenberger in a way she calls “generational.” Her parents met working at the CMH Monashees Lodge just downstream from Mica. Her father went on to run the ski shop, called Lusti’s (the origin of her nickname), at Panorama Mountain Resort for the past 37 years. The slopes outside the town of Invermere, British Columbia—the headwaters of the Columbia River—were her daycare, and where her ski-racing career began. To this day, the mentality of pushing out of the starting gate in full charge shapes her skiing. “It’s always ingrained in a ski racer to go as hard as you can,” she laughs. Her racing prowess landed her on the Canadian Alpine Ski Team, where she achieved top-ten results on the World Cup and competed in the 2006 Winter Olympics. But it’s her move after that experience that defines her reputation: while the Olympics is the peak of most athletes’ careers, Lustenberger looked for how to expand from there. “There’s a certain level I want to ski at to feel like I’m challenging myself to get that satisfaction, that feeling that you’re always pushing yourself. To plateau would become quite boring.”

At a young age, Lustenberger had already discovered ski touring in the Jumbo Valley out Invermere. Upon retiring from ski racing, she transplanted to the powder Mecca of Revelstoke to cut her teeth in the backcountry of the Selkirk Mountains. Her drive to learn more about conditions, skills, and techniques for getting into and managing big lines led her to become a certified Association of Canadian Mountain Guides ski guide. That training, and her continual use of those skills through guiding, gives her a profound understanding of big-mountain environments that few professional skiers have.

THREE DAYS AFTER that first glimpse of Wildcat, the helicopter drops Lusti and Tudor on that summit, and shuttles the film crew to camera angles on adjacent ridges. From their clear blue vantage point, both skiers see Kinbasket Lake snake out far below on its journey south to the U.S. border. “With any line, you look at hazards, anticipate what the snow will be like—will it change, will it slough, where are the safe zones—so you can anticipate everything,” she says. “I’d already decided in my head how I would ski it, where I would turn. But then you’re on top of it, and it just rolls away into nothing.”

While the crew positions cameras and drones and bets on light, Lustenberger waits. She likens it to cliff jumping: the longer you look at it, the higher the jump seems. As she stands there, the concept of the risk associated with reaching her full potential plays on her mind. She is a knowledgeable ski mountaineer with an eye for calculated assessments that guide her movements in big-mountain conditions, so she knows full well those cameras place a new weight on an already heavy line. “If I were skiing this line without filming, I could relax, break it into two pitches,” she explains. “To be up there, racing your slough, trying to look fast and fluid, and ski as strong and powerful as you can—it adds an element of pressure. You build up the line in your head, and you build the perception of your potential, and those things make you want to push. But it’s this fine line in the mountains.” It’s the inherent risk of chasing the unicorn.

She checks her boot buckles for the third time, her pack straps for the fifth. Finally, a voice cracks over the radio, “Athlete ready?” She drops and slips into the zone, automatically executing that checklist in her head. She turns on that beautiful hanging face exactly where she rehearsed it, keeps laser track of her slough, and flies past unneeded safe zones. Just like that, she’s at the bottom, looking up. There’s the addictive glorious high, she says, but also something else. “In the mountains, you can be rewarded by skiing safely, but I always reflect, even when I have a positive outcome, how it went, where I could have opened myself up to more air. I thought about that line for a long time afterward.”

The film project is wrapped. Wildcat Peak ticked off, but she isn’t about to rest. Christina Lustenberger is already dreaming of another line she’s been eyeing in the Purcell Mountains where she spent her childhood. Catching the unicorn has never been the point. It’s always in motion, dancing just ahead of her on that fine line between risk and full potential.

Cassidy Randall is an adventure writer who splits her time between Revelstoke and Montana, where she chases her own unicorn. Thankfully, it rarely leads her to ski lines that make her pee her pants.

Related Stories

Mountain In the Hallway Film Explores Cancer and Mountain Life

Teton Gravity Research has released the film "Mountain in the Hallway" about two fathers battling cancer and their…

Insane Mountain Beat Boxin’

We don't know who this guy is, or where he came from. He showed up at the Kootenay Coldsmoke PowderKeg Slopestyle last…

Just an Ordinary Skier

No doubt a lot of the footage that will be featured in this film will come from the Kootenays. Seth Morrison loves his…

The Gathering at Red Mountain

This upcoming Easter weekend RED and POWDER Magazine are presenting the 2nd annual Gathering at RED. Come hang with…

Life Cycles Almost Done

KMC Editor Mitchell Scott has been working as a story consultant and script writer for the Stance Film Crew for the…