The avalanche report said they were good to go. The terrifying outcome of the day should make us stop and think – more than twice. By Dave Robertson.

It was 7:10 a.m. on April 5, 2018, when Tim Banfield glanced at the avalanche bulletin for Banff National Park and saw green, green, yellow. In his words, a day of backcountry skiing that was “good to go.” He’d been planning to photograph ice climbers on the Stanley Headwall, but after looking at the bulletin online, he decided to ski into Mount Temple and scout some routes with a couple of experienced climbing friends. He rushed to pack his gear, and by 7:30 a.m., he was headed for Lake Louise, Alberta.

An outdoor sports photographer, Banfield spends more than 50 days a year climbing and skiing, mostly with professional outdoor athletes. He has plenty of first-aid training from his time in the military and has taken a couple of avalanche courses. But there are things they don’t teach you at avalanche school—like how to find someone buried under four metres of avalanche debris.

After a great day of scoping and skiing, Banfield, fellow climber Maia Schumacher, and another friend were ascending Sentinel Pass at 4:20 p.m. That’s when he saw shooting cracks in the snow beneath his skis. He was in the lead, and before he could warn the others, they were caught in a size 2.5 avalanche. Banfield made a self-arrest to stop his slide and immediately started monitoring the others. He watched Schumacher ride the surface of the avalanche in a seated position, and when it stopped, she was only partially buried. The other skier, who asked that her name be withheld, disappeared beneath the snow. Moments after the slide stopped, Schumacher dug herself out. Together, she and Banfield completed a quick transceiver search of the debris area and got a solid fix on the buried skier. When they finished a fine search, they were dumbfounded to learn that the victim was buried 3.8 metres below the surface. Banfield immediately thought, “She’s dead.”

He had good reason. In a 1996 study, University of Calgary avalanche researchers Bruce Jamieson and Torsten Geldsetzer compared the survival rates of 130 avalanche victims to their relative burial depths. They found those buried in one to two metres of snow had a 40 per cent chance of survival, while those in two or more metres only had a 10 per cent chance. The odds at Sentinel Pass were not good.

Banfield and Schumacher immediately started probing for the victim. To save weight, Banfield was carrying a shorter 2.4-metre avalanche probe, a decision he immediately regretted. Schumacher was carrying a 3.2-metre probe, which was still a half a metre short of the victim’s depth. Banfield realized that they needed a shallower probing surface, and he quickly excavated a square pit about a metre deep and started probing again. They immediately hit something hard. It wasn’t a good sign. In avalanche skills training, students learn that when a probe hits a buried person, it should feel soft or squishy. If it feels hard, they’ve likely struck the ground or something else inanimate. Banfield and his partner now faced a critical dilemma. “I didn’t know if it was a rock or a block of ice,” he explains. They could try and redo their search, but at this juncture the victim had already been buried for over five minutes. Time was running out.

Desperate to rescue their friend, Banfield and Schumacher quickly rechecked their transceivers and took a calculated risk. In a rush, they started digging downward from an arbitrary spot less than a half a metre downslope from the probing area. Soon, Banfield found himself inside an enormous pit, “I was totally prepared to go into that hole and do AR [artificial respiration] upside down.” Each took a turn digging while the other removed snow from the rapidly growing hole. When they spotted the orange fabric of their friend’s pack, Banfield was surprised they had actually found her. As they continued to dig and heard her muffled shouting, they were even more surprised to discover she was alive, alert, and uninjured. He now believes that the probe hit her in the back of the head or struck a hard object in her pack.

Banfield retrieved an inReach device from the victim’s pack and struggled with sending an SOS. Frustrated, he passed it to Schumacher and continued the recovery. Parks Canada received their message just after 5 p.m. and sent a helicopter. Exhaustion set in, as it took the rescuers another two hours to get the victim out of what was now an enormous pit.

This video gives you an idea of the terrain Banfield and his friends were skiing that day.

Looking at data from his watch, Banfield estimates that the slide took place at 4:21 p.m. and that the victim’s head was clear by 4:48 p.m. Fortunately, she was buried upright. Banfield estimates that it would have taken another 10 minutes to uncover her head if she had been upside down.

After talking with snow professionals, he believes that the characteristics of the avalanche also contributed to their success. Avalanche training teaches that avalanche debris makes rescues difficult because it is hard and heavy, like wet concrete. Banfield’s experience was different. “(The slide) just slumped and stopped…. Not as much energy was released, and so the debris we dug out was not as consolidated.”

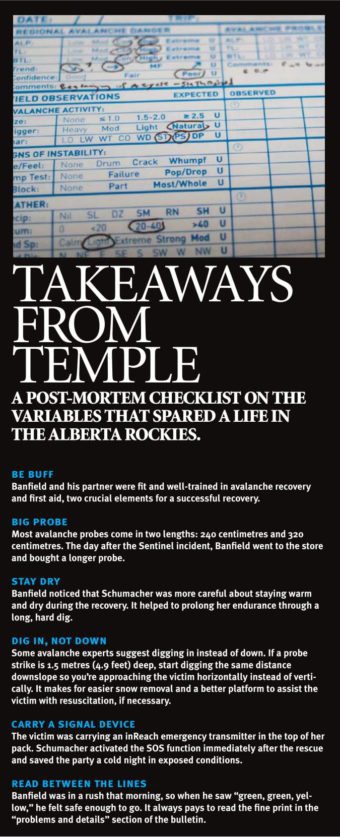

On reflection, Banfield is pretty open about other things that contributed to the incident. “If you read the details [of the avalanche bulletin], which is part of the human factor in this incident, they had suggested to be careful of this aspect in the Louise group. But,” he continues, “I saw green, green, yellow, and I was like ‘Woo! We’re going to go!’”

When they finished a fine search, they were dumbfounded to learn that the victim was buried 3.8 metres below the surface. Banfield immediately thought, “She’s dead.”

According to Doug Latimer, an Association of Canadian Mountain Guides ski guide and instructor, we should all be more thoughtful about interpreting avalanche risk. Statistics show that most incidents happen when the rating in the avalanche bulletin is “considerable,” or yellow. In the middle of the scale, it’s the rating with the least certainty. Latimer argues that the definitions of risk used in international standards mean a “considerable” hazard rating is actually the riskiest. “Considerable hazard means that you might be in an avalanche or you might not.” He advises using the same level of caution you might use for higher ratings.

A few weeks after the incident, Banfield and his rescued friend went back to the pit on Sentinel Pass to salvage her skis and to peer into the hole again. He also contacted more avalanche experts to learn about similar burials. He has yet find anyone else who has survived a four-metre burial. “It’s really crazy what we pulled off there.”

Dave Robertson is a writer and skier from Calgary. He is currently in the market for a longer avalanche probe.

Related Stories

Avalanche Awareness Course for Youth

The Avalanche Awareness Beyond the Boundaries Society put on another successful 3 day AST training course at Whitewater…

Snake River Float Avalanche Airbag Save

This avalanche airbag footage was caught on January 25th, 2012 in the Snake River backcountry near Montezuma, Colo. It…

Slaying Hut Pow at Mt Carlyle Lodge

You gotta love Kootenay Hut life. Especially when you're with characters like the Bald Bomber. Cruising through white…

Five Full Runs – by Nate Smith

Watch this beautifully shot, ridiculously skied big-mountain session featuring Tanner Hall at Retallack Lodge. Shot…

Facts You Never Knew About Mt Baldy

As the world gets busier, people move faster and the memory of "the good ‘ol days" seems to slip away, it's good to…