Ruling against the questionable aims of an American billionaire, BC’s Supreme Court has granted the public access to parts of Canada’s largest privately owned cattle ranch. Despite the high court’s decision, some of the province’s outdoor recreation stakeholders wonder if too many cows have already left the barn. Story by Jeff Davies.

In the wake of a landmark court ruling last December, British Columbia’s outdoor recreation community is watching closely as the future of land access sits in the balance. But none are watching more closely than Rick McGowan, a director of the Nicola Fish and Game Club, avid angler, and one of the men at the centre of the court case. His eyes are focused intently on Justice Joel R. Groves of the Supreme Court of British Columbia, and the future of the province’s backcountry access. On December 7, 2018, Groves issued a ruling that might just blaze a trail in British Columbia jurisprudence by ruling in favour of nature lovers — hikers, mountain bikers, campers, and anglers — even though that decision is being challenged in the BC Court of Appeal.

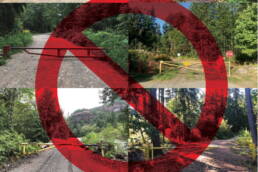

The ruling says that in the Nicola Valley, south of Kamloops, Stoney Lake Road and the two lakes it accesses, Minnie Lake and Stoney Lake, which are prized by anglers for their fine trout fishing, are indeed publicly owned, just as McGowan and others in his fish and game club have contended. The lakes and access road are surrounded by private ranchland owned by the Douglas Lake Cattle Company and have been sequestered behind locked gates for years. The BC government has been reluctant to assert its ownership of this public property. “It is shocking that any corporation could take for its own benefit, with no legal right, a road,” Justice Groves writes. “It also seems clear that it was done for the express purpose of prohibiting access to two lakes . . . in order to create a recreational fishing business.” A private business, that is, where people pay to fish, a far cry from the public access Rick McGowan enjoyed when he caught trophy trout in the lakes as a child back in the 1960s.

The dispute goes back to 1976, when the ranch owners had a bypass built around Stoney Lake Road to assist logging operations; then began sporadically blocking access to the two lakes. “That’s how long I’ve been fighting this bullshit,” McGowan tells me. The road was permanently closed in the 1980s and decommissioned around 1990; the exact date is unclear.

The dispute goes back to 1976, when the ranch owners had a bypass built around Stoney Lake Road to assist logging operations; then began sporadically blocking access to the two lakes. “That’s how long I’ve been fighting this bullshit,” McGowan tells me. The road was permanently closed in the 1980s and decommissioned around 1990; the exact date is unclear.

McGowan and his angling friends are certainly up against a formidable adversary. The owner of the Douglas Lake Cattle Company is American billionaire Stan Kroenke, who also owns a number of pro sports franchises, including the NHL’s Colorado Avalanche. The lake-ownership issue went back and forth for years, generating hundreds of pages of legal documents, before it finally hit the courts in the spring of 2013, when the Nicola Fish and Game Club sought a ruling that acknowledged Minnie and Stoney lakes and the access road are publicly owned. There were numerous claims and counterclaims, with anglers accusing the ranch owner of acting unlawfully, and the owner accusing the anglers of trespassing and theft. The various actions were rolled into one lawsuit, which went to trial in the Supreme Court of British Columbia in early 2017.

When the long-awaited ruling finally came down, Groves directed the Douglas Lake Cattle Company to remove the gates blocking access to the two lakes. Victory, or so it seemed at the time. “We are in disbelief right now but very happy,” McGowan told reporters the day after the court ruling. “We always knew what evidence we had and the law, but it was just how we were going to get the government and the private landowners to acknowledge that the law is there and they have to abide by it.” The ranch owner and the manager, Joe Gardner, were, in Groves’ words, “taking the law in their own hands and closing, by virtue of a lock and intimidation, a public road.”

When the long-awaited ruling finally came down, Groves directed the Douglas Lake Cattle Company to remove the gates blocking access to the two lakes. Victory, or so it seemed at the time. “We are in disbelief right now but very happy,” McGowan told reporters the day after the court ruling. “We always knew what evidence we had and the law, but it was just how we were going to get the government and the private landowners to acknowledge that the law is there and they have to abide by it.” The ranch owner and the manager, Joe Gardner, were, in Groves’ words, “taking the law in their own hands and closing, by virtue of a lock and intimidation, a public road.”

The judge cites evidence that Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure managers were well aware the road and lakes were publicly owned but failed to act to protect public access, writing that, “Over 20 years, a privately-held corporation, owning a large swath of land, prohibited the public from driving on a public road and the Province did nothing.” The ruling has sent growing ripples through the province’s outdoor recreation community, which has been fighting for years to keep the backcountry open, even as landowners, particularly those in the resource industries, have been closing and locking gates.

Wes Mussio, a lawyer, cartographer, and the co-founder of the Backroad Mapbook series, welcomes the court ruling, but he worries it will be a “one-off” situation.

The Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development, which oversees much of the backcountry, is declining to comment on the case while the issue remains before the courts. But user groups are not holding back. “It’s a huge precedent,” says Kim Reeves, chair of the Outdoor Recreation Council of BC. “It’s strongly worded.” But after the deep-pocketed ranch owner announced plans to appeal the verdict, McGowan became far more cautious in his response. “It’s not really a victory yet,” he told me in May. Then in early July, the parties and their lawyers returned to court in Kamloops to work out the details of the previous ruling. The judge awarded costs of $350,000 to the Nicola Fish and Game Club, to be split 50\50 between the ranch and the BC government. He also left vehicular access open to the two lakes, at least until the province clarifies its position or a higher court decides otherwise.

In a telephone interview the day after the July hearing, McGowan sounded tired but triumphant: “It’s amazing. We’re not trying to blow my horn or the club’s horn, but we tackled the giant here, and to come out on the right end of it is a miracle.”

In a telephone interview the day after the July hearing, McGowan sounded tired but triumphant: “It’s amazing. We’re not trying to blow my horn or the club’s horn, but we tackled the giant here, and to come out on the right end of it is a miracle.”

Erica Stahl, a lawyer with West Coast Environmental Law in Vancouver, which helped fund the action by the Nicola Fish and Game Club, notes the lack of a complete inventory of provincial roads in British Columbia. The current list doesn’t include the original “Crown grants,” road allowances dating from colonial times. Stahl points to the unusual step Groves took by attaching an epilogue to his ruling, challenging the British Columbia government to clarify the issues. In the judge’s words, “If you own the lakes of the province, which you do, can you not regulate access? There really is no point to ownership otherwise.”

Until the government acts, Stahl says, it will likely be up to user groups to pursue litigation to clarify ownership and remove gates. But, she adds, “I think it is extremely significant for a court to come down so firmly in favour of public access and to clarify what public roads are public. It should be very simple, but in fact in BC, we often see these public roads locked away behind private gates and the same with public lakes.”

Wes Mussio, a lawyer, cartographer, and the co-founder of the Backroad Mapbook series, welcomes the court ruling, but he worries it will be a “one-off” situation. “It would be nice if the forest companies were to take heed of this and open up gates for public access,” he says. But, so far, there is little sign of that in the backcountry.

Wes Mussio, a lawyer, cartographer, and the co-founder of the Backroad Mapbook series, welcomes the court ruling, but he worries it will be a “one-off” situation. “It would be nice if the forest companies were to take heed of this and open up gates for public access,” he says. But, so far, there is little sign of that in the backcountry.

It’s a province-wide issue, but it is particularly acute on southern Vancouver Island, where much of the working forest is privately owned, dating from the controversial Esquimalt and Nanaimo railway land grant in the 19th century. In 1883, coal baron Robert Dunsmuir signed an agreement with the BC government that gave him title to more than 300,000 hectares of resource-rich land, in return for building the railway. But much of the land has since been sold and resold many times. Today many lakes and campsites that were once open to the public are now off limits, and outdoor recreationalists are seething. “We have lost our access year-round to so much beautiful recreational land, it’s ludicrous,” Lisa Hagen of Port Alberni says in an online petition she launched more than three years ago. She gathered more than 13,000 signatures from people demanding the right to access recreation areas in the Alberni Valley. Hagen and others were counting on local MLA Scott Fraser, a member of the NDP cabinet who championed this issue while in opposition, to raise their concerns in Victoria and get some action. By this spring she was getting impatient, “Nothing has changed. It’s very frustrating.”

In a written statement, Fraser tells me he understands the importance of balancing the needs of local residents with the rights of property owners concerned about vandalism, wildfires, and public safety. “There is more to come in the coming weeks,” he says. He’s attached a backcountry access report that proposes a number of solutions, including designating logging mainlines as Crown land and purchasing land to ensure access to parks.

In a written statement, Fraser tells me he understands the importance of balancing the needs of local residents with the rights of property owners concerned about vandalism, wildfires, and public safety. “There is more to come in the coming weeks,” he says. He’s attached a backcountry access report that proposes a number of solutions, including designating logging mainlines as Crown land and purchasing land to ensure access to parks.

Barry Janyk, the executive director of the Federation of Mountain Clubs of BC, agrees there is a problem with vandal-ism that must be addressed. “Some people ruin it for others, as we know,” he says. “They use the backcountry and the back roads for garbage dumps, [to] shoot things up, have fires and parties. The irresponsible actions of some ruin it for everybody.” Janyk is hoping the province will introduce what’s known as right to roam legislation, something Scotland has implemented and Green Party Leader Andrew Weaver has proposed. It would allow the public, at least those on foot, to traverse private land to access public land.

In the Nicola Valley, meanwhile, McGowan, says various court actions may last the rest of his life. “There’s a movie here for sure,” he says with a laugh. But he’s also confident his actions will help ensure access to the backcountry for generations to come. “There’s no doubt about it. It’s just going to be a longer fight than I thought it was going to be.”

In the Nicola Valley, meanwhile, McGowan, says various court actions may last the rest of his life. “There’s a movie here for sure,” he says with a laugh. But he’s also confident his actions will help ensure access to the backcountry for generations to come. “There’s no doubt about it. It’s just going to be a longer fight than I thought it was going to be.”

Jeff Davies

Jeff Davies is a freelance writer and retired CBC political report based in Victoria, British Columbia. He left the legislative press gallery in 2012 to spend more time enjoying the great outdoors and writing about it.

Related Stories

Mount Carlyle Backcountry Lodge

Our friends at Mount Carlyle Backcountry Lodge have a few spots open. Read about their iconic leader the Bald Bomber…

New West Kootenay Backcountry Guide

The first of it's kind for the region, the newly minted West Kootenay Touring Guide provides backcountry riders with…

Some Thing Else — Backcountry Shred Flick Trailer

Powder Whore is back at it, check the teaser!

Some Thing Else — Backcountry Shred Flick Trailer

Powder Whore is back at it, check the teaser!

STAND movie hits BC in early May

From our Friends Anthony Bonello of b4apres Media, and Nicolas Teichrob, photographer comes the cinematic premier of…

Creaking Tree String Quartet touring BC

Two time Juno nominees, The Creaking Tree String Quartet are coming to British Columbia to promote there fourth Album.…