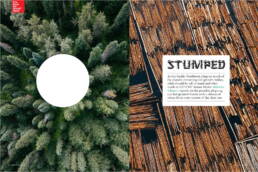

As the Pacific Northwest clings to much of the planet’s remaining old-growth timber, what should be left to stand and what needs to fall? CMC Senior Writer Malcolm Johnson reports on the paradox plaguing our last greatest forests with a chorus of voices from every corner of the clear-cut.

A few decades ago, old-growth forests were a tale that stood taller than most. You couldn’t open a newspaper without a reminder of the pitched battles being played out in the backwoods between loggers and environmentalists, some of them complete with arson and sabotage. Today, however, forestry seems to have faded from the public consciousness, only occasionally trending at the top of newsfeeds. But the basic business template that’s been in place since the 80s is still trucking: timber companies are still chopping, protestors are still protesting, and politicians are still issuing carefully worded statements about their firm commitment to jobs, sustainability, and the rights of Indigenous Peoples. All the while, irreplaceable old-growth forests keep getting converted into cut blocks, and working towns and families keep struggling to get by.

It’s no easy thing to manage a landscape in a way that balances the environment and the economy; once you start digging in, it doesn’t take long to see that few involved are satisfied with the status quo: one side wants more forest protections and the other wants more land available to log. There’s not much space for compromise, and the dialogue often devolves into mud-slinging that pits some version of “You’re a bunch of rednecks who don’t care about the planet or the future” against “You’re a bunch of spoiled, ignorant NIMBY yuppies trying to take our jobs.” Meanwhile, the companies make the money and keep the lobby pressure up to advance their own interests. It’s not an atmosphere that fosters cooperation, innovative thinking, or courageous stewardship.

On the largest scale, logging and development have converted what was once an unbroken swathe of ancient forest stretching from northern California to Alaska into a patchwork of cities, roads, infrastructure, and second- or third-growth forest, with intact old growth remaining mostly in small and scattered parcels. In total, over 70 per cent of old-growth conifer forests have been lost throughout the Pacific Northwest, and that number increases every year. Forestry’s economic contribution, however, is essential. Over the past decade, British Columbia’s annual timber harvest has been 74 million cubic metres, enough to fill two million shipping containers. The industry contributed $12.9 billion to the province’s gross domestic product in 2016, and the forest industry directly generated 140,000 jobs in British Columbia. These large numbers tell us a lot of families depend on logging, and you’d have to be a real eco-asshole to want those people to go broke.

Here are some other interesting numbers: Currently, old growth makes up 50 per cent of the total timber harvest on the mainland coast and Vancouver Island. Of the remaining forests on Vancouver Island, 21 per cent are old growth, of which only six per cent is protected. Another crucial number to note about an industry often framed as sustainable or renewable is that, according to researchers at Sierra Club BC, not one square metre of the province’s logged forest is capable of returning to its original state because of the planet’s unstable climate. And the costs of forestry aren’t just ecological: one of the most sobering facts out there is that 97 workers have been killed while harvesting British Columbia’s trees in the last 10 years.

The basic dilemma, economically speaking, is that we have a limited supply of high-value old-growth forest, but we keep subtracting from a shrinking balance without immediately adding back. Environmentally, the loss of old-growth forests is a major problem, since they are strongholds of biodiversity that provide critical ecosystem services, like clean air and water. Old trees also store more carbon than young ones, and recent research suggests almost 70 per cent of the carbon they store is pulled from the atmosphere in the second half of their life. Though it’s harder to quantify, the cultural and spiritual importance of unspoiled old-growth forests is hard to overemphasize, especially for Indigenous Peoples, as is the value of old growth to the province’s tourism sector, which now generates almost twice as much revenue as logging.

For the forestry industry, losing old growth is a big problem too. Old-growth forests tend to generate more money per hectare than second or third growth — if a blanket ban on old-growth logging was put in place, as some conservationists call for, there would be a lot of people suddenly missing their rent. Secondary industries that rely on old-growth wood, which is often far superior in quality to second-growth lumber, would also be affected, from custom homebuilders to backyard snowboard shapers. On the provincial scale, British Columbians also benefit from the forest sector in the form of tax payments, funding for community projects, and networks of roads that access some of the province’s most beautiful places. If the money all grows on trees, where does the money come from once the trees are all cut down?

It’s a complex problem, but many feel new ways forward can be found. And despite the often-acrimonious debate around old-growth logging, there are already examples of opposing sides coming together to find collaborative solutions. In 2016, the unprecedented Great Bear Rainforest agreement was signed, with forestry companies, environmental groups, the provincial government, and Indigenous governments agreeing to a management framework that protected cultural heritage sites and 3.1 million acres of rainforest from industrial logging, while allowing appropriate industry access. There are also steps on which almost all reasonable people agree, like maximizing the productivity of second-and third-growth stands, investing in value-added processing that turns timber into beautiful and useful products, and remembering that a healthy future economy will depend on an equally healthy environment.

None of these are simple tasks, but they’re not impossible, and how to take the best care of our forests is something everyone in the Pacific Northwest — and the world — should keep in mind.

Malcolm Johnson is an outdoor and environment writer from Vancouver Island now living and working in northern British Columbia.

Note: Two other industry groups, the Truck Loggers Association and the BC First Nations Forestry Council, declined to comment for this story.

What’re your thoughts about the British Columbia forestry and its remaining old growth? Please leave your comments below.

Related Stories

STAND movie hits BC in early May

From our Friends Anthony Bonello of b4apres Media, and Nicolas Teichrob, photographer comes the cinematic premier of…

Creaking Tree String Quartet touring BC

Two time Juno nominees, The Creaking Tree String Quartet are coming to British Columbia to promote there fourth Album.…

Cool New Video by Nelson BC’s Best Western Hotel

The world of the webisode gets funner by the day. This new piece by the local Nelson family that runs the town's Best…

Jumbo Gets the Go Ahead by BC Government

It's been a point of debate in the Kootenays for nearly 20 years. Today it looks like Jumbo Glacier Mountain Resort is…

New BC Bike Race Movie Lands Today

BC Bike Race has released its third feature film, "The Journey," documenting the 2017 event. Watch it below. Director,…

3 BC Cities Named World’s Best For Rock Climbing

In a recent article by Carlo Alcos on the Matador Network travel site, three cities in British Columbia and one in…