Alpine canyoning is a relatively new sport in Canada, but despite the dangers, which include hypothermia, rockfalls, and the possibility of plunging off high peaks, it’s growing in popularity. As our writer discovers, sometimes it’s worth chasing waterfalls. By Katie Graham. Photos by Greg Horne.

We’ve been in the water for 14 hours. My teammate Guillaume Coupier stands on a rock ledge above one of the 40 waterfalls we’ve encountered so far during our attempt to descend the most prominent canyon on the west face of Mount Robson, the highest mountain in the Canadian Rockies. He tosses a rope bundle into the blackness of night and then flicks it, studying its orange ripples to determine whether it has reached the bottom of the waterfall. If the bottom is further than 30 metres away, the situation could be dire because the roar of the water will drown out his shouts for help once he drops over the edge. Twice more he pulls the rope up and throws it out. We watch intently, but each time the coils swing into the deluge and disappear. We have no way of knowing how far it is. Coupier lets out an exasperated grunt and starts rappelling anyway. I tell myself, “Slow is smooth and smooth is fast” as I watch him, nervous he will make a mistake.

In September 2020, Coupier, who hails from Field, British Columbia, and I joined Greg Horne and Matt Kennedy of Jasper, Alberta, and Colin Magee of Canmore, Alberta, to attempt the first canyon descent of the west face of Mount Robson. Known to the Texqakallt Nation as Yexyexéscen, or the Mountain of the Spiral Road, the 3,954-metre peak is located about 30 kilometres north of Valemount, British Columbia, and is famous for resembling a giant layer cake. Since 2016, we had visited the canyon on four separate occasions to rig many of the anchors, but this would be our first full push from top to bottom.

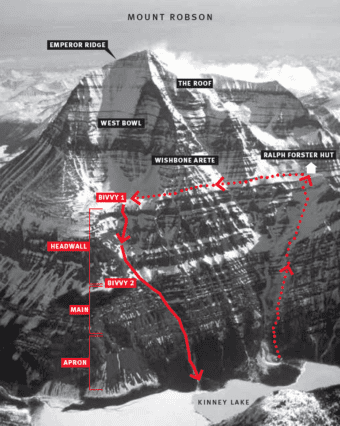

The adventure would require a steep hike from Kinney Lake to the Ralph Forster Hut, a nerve-racking traverse across a ledge about two-thirds up the west face, an uncomfortable bivvy beside the canyon, and a 1.2-kilometre descent — no less than 51 rappels in total. By comparison, the renowned Polar Circus ice climb in the Rockies, which can also be done as a canyoning excursion, involves 17 rappels.

Canyoning, or canyoneering as Americans call it, is a growing sport in this country, so much so that the Canadian Canyoning Association was formed in 2020 to establish guidelines for commercial guiding and recreationalists. A typical canyoning experience begins at the top of a series of waterfalls and the team uses specialized gear to descend, pulling the ropes down after every pitch. It’s a sport rife with danger because once you’re committed to a canyon, you can’t climb out again. Rain, flood debris, and swift water are threats. Add in an alpine environment, like the one on Mount Robson, and obstacles are compounded: pack loads double, the weather is more unpredictable, and hypothermia is a constant concern.

At 11 p.m. on day three, our longest canyoning day, I’m anxious because risk factors, like darkness and fatigue, are starting to stack up. I watch as Coupier leans back on the rope and begins walking backward down a shallow trough toward the edge, where the flowing water drops away. I need a reprieve from the push of the waterfall and its cold embrace, so I clamour onto a bank of rocks, get settled, and then look up. Horne adjusts his headlamp, illuminating the airborne droplets; it looks as though he’s surrounded by a million tiny candles. I’m overcome with awe. The water ricochets off his shoulders and when he looks down, a crystal peacock tail shoots up over his shoulders. He shifts and his entire body cuts through the spray like a superhero emerging through a veil of his own electricity. My anxiety dissipates and I’m reminded of why I’m here: by allowing myself to be in a vulnerable situation, I’ve accessed something uniquely beautiful. There is no place I’d rather be.

Two hours later, we collapse on a carpet of moss at the base of the canyon, delirious in the satisfaction of our first descent. We agree to call the feature Waffl Canyon after mountaineering pioneer Newman Waffl, who once said, “Mount Robson is not so much difficult as dangerous. It is no mountain to trifle with.” Sadly, he learned this first-hand during an attempted solo summit in August 1930. An avalanche swept him off the west face near the water drainage that leads to the canyon that now bears his name, an enduring reminder of the fact that mountains can give so much — and take it all away.

Katie Graham is a cave and canyon explorer based in Calgary, Alberta. She was involved with the discoveries of the deepest and second-deepest caves in Canada. An accountant by trade, Katie has switched gears from her corporate gig to spend more time following her passions.

Related Stories

Insane Mountain Beat Boxin’

We don't know who this guy is, or where he came from. He showed up at the Kootenay Coldsmoke PowderKeg Slopestyle last…

The Gathering at Red Mountain

This upcoming Easter weekend RED and POWDER Magazine are presenting the 2nd annual Gathering at RED. Come hang with…

The Gathering Returns to Red Mountain

Presented by Salomon, the Gathering at Red Mountain, an event of mountain photographers, filmmakers, and artists is…

Framed in Leavenworth With Coast Mountain Culture

This past weekend, CMC was on hand to sponsor and participate in Leavenworth's Framed Photographer Invitational, where…

Coast Mountain Culture Launches Premiere Issue

You may have seen a copy of the new Coast Mountain Culture Magazine (CMC) floating through outdoor veins throughout…