British Columbia’s grizzly bears rule the peak of the food chain. But they’re being left to waste at the bottom of the government’s conservation priority list. Their dwindling population is on the verge of further decline, yet the province still allows them to be slain for sport. Is there still time to spare one of the province’s most colossal creatures?

My dad’s bifocals were as thick as Coke-bottle glass and fogged up like the windscreen of a Volkswagen Bug in winter. He never did see the grizzly casually browsing for berries at the side of the trail a few arm lengths in front of us. We were trudging down the Keen Creek trail from Kokanee Glacier, located in the West Kootenay’s Kokanee Glacier Provincial Park. There was a steady, demoralizing drizzle. Clouds formed a low ceiling that oozed into the forest.

I looked at my feet instead of the trail ahead. My brother was in the lead and when he rounded the bend was the first to see the bear. The fur on its silvery hump glistening from the rainfall, its snout probed upwards the way bears, with their notoriously poor vision, sniff out a scene. We froze in our tracks, petrified by 500 pounds of fur and bulk that could shred us to pieces in an instant.

Thankfully, the grizzly was nonplussed, content with a late-summer bumper crop of berries. The giant omnivore simply wandered off into the misty forest in roughly the same direction we were travelling, mind you, which kept us on edge for the remainder of the walk. For whatever reason — an abundance of available food, no cubs nearby, the fact that our scent had been carried on a forewarning invisible breeze or simple dumb luck — the grizzly didn’t perceive a threat. Leaving us only with memories of an exhilarating encounter.

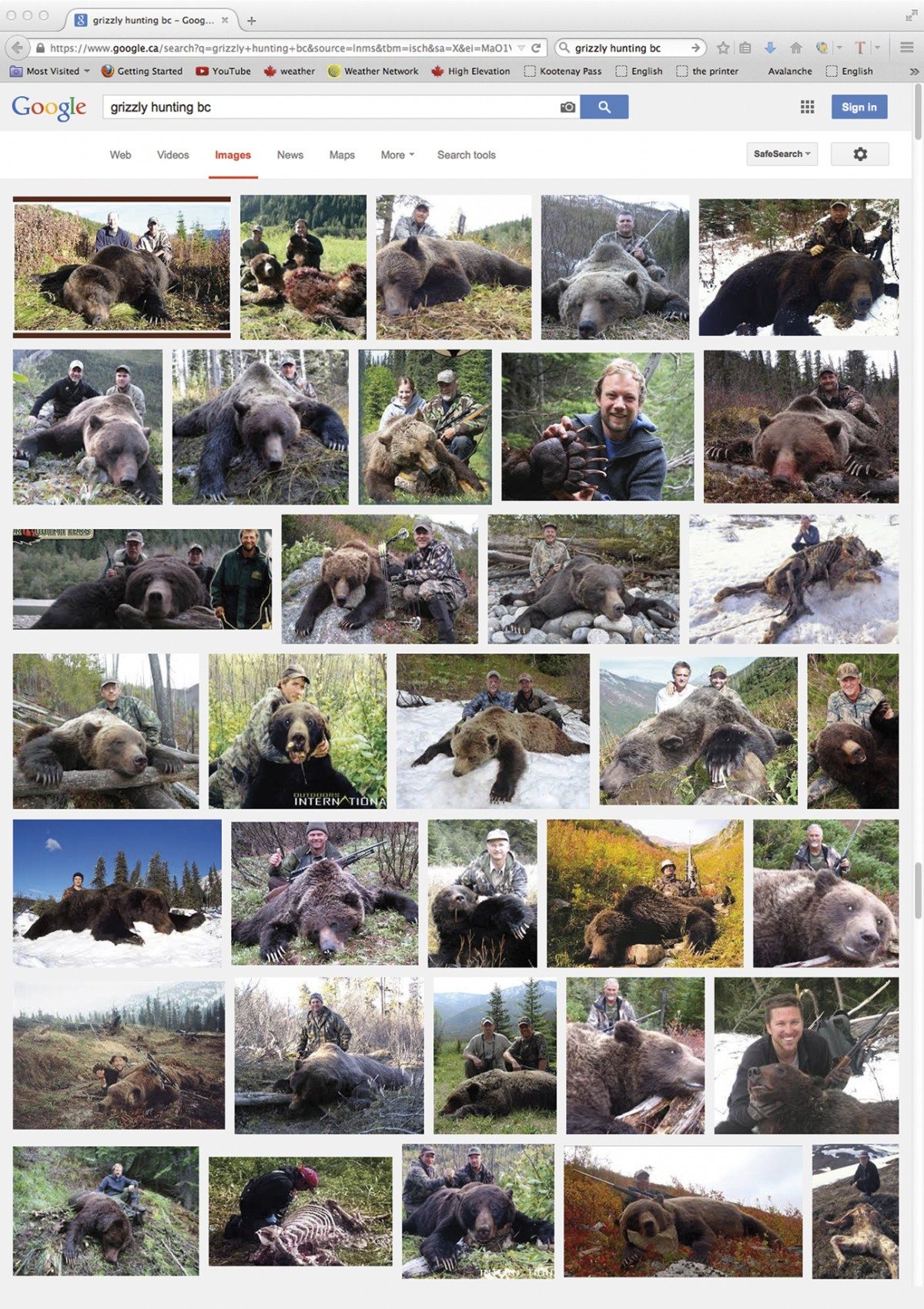

The Grizzly bear carries the Latin name Ursus arctos horribilis, which means “the horrible brown bear.” No other animal in British Columbia inspires the same fear, awe and controversy. Conservationists and government agree on little when it comes to these creatures: the science used to estimate populations, the amount of protected habitat needed to sustain them, or the annual and unpopular autumn trophy hunt that most public opinion polls say the overwhelming majority of British Columbians oppose. In 2014, the provincial government fuelled the fire when it raised the number of grizzly tags to 1,800 from 1,700 the year before, and they opened two previously closed areas to hunting.

British Columbia is home to half of Canada’s grizzlies. A century ago, there were an estimated 35,000 roaming the province. Today, depending on who you talk to and whose science you believe, there are anywhere from 6,000 to 15,000, the latter being the figure the provincial government currently uses for its management and hunting quotas. Every year, trophy hunters shoot between 300 and 400.

Grizzlies are extremely susceptible to extraneous pressures, whether it’s habitat fragmentation from logging, mining and sprawling development, or targeted hunting. Non-resident hunters, for example, will pay between $15,000 and $25,000 for a guided grizzly hunt. These bears roam large territories, as much as 4,000 square kilometres. Adding to their sensitivity within the ecosystem, they also have low reproductive rates. Females have cubs only once every three or four years, and natural mortality for cubs under one year old is high. The grizzly bear is also a top-of-the-food-chain predator, and its health is a key indicator of overall ecosystem health.

It’s for these reasons that, since 1992, the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada has recognized northwest grizzly populations as a species of special concern. Under this context, the shooting of these apex predators is increasingly indefensible.

Even putting aside the idea that grizzly bears have intrinsic value and the right to peacefully exist, you can distill the issue down to a frank economic conclusion against the hunt. There’s mounting evidence that a live bear is worth much more to the province than one that is hunted and killed.

In 1995, the British Columbia Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks published the Grizzly Bear Conservation Strategy, which was meant to be a turning point for the troubled species in the province. It boldly proclaimed the animal as the “greatest symbol of the wilderness,” one whose survival “will be the greatest testimony to our environmental commitment.” The strategy’s ultimate objective was to establish one large core protected area for each of the province’s grizzly-bear ecosystems, linking them with habitat corridors.

However, rather than a turning point, the strategy has become a source of controversy that still dogs the government two decades after it was published. It supplies endless fodder for critics, and for good reason: across the province, there’s no plan in place to recover these populations. Since the strategy’s implementation 20 years ago, nine of the province’s 57 grizzly populations remain in threatened status, all of them in southern British Columbia. This includes a tenuous population centered in and around the Jumbo Glacier Resort — a proposed ski development in the southern Purcell Mountains led by Kicking Horse Mountain Resort developer Oberto Oberti. It’s been on the table for more than two decades but is largely opposed by Kootenay citizens.

In a March 2014 report provocatively titled Failing BC’s Grizzlies, independent biologist and author Jeff Gailus concluded that by “almost every measure the BC government deserves failing grades for its implementation of the 1995 Grizzly Bear Strategy.”

A year earlier, a group of five scientists published a paper out of Simon Fraser University with an equally damning conclusion: according to lead author Kyle Artelle, government methodology for generating population estimates, and consequently kill limits, had built-in uncertainties that lead to overinflation of quotas. Artelle and his colleagues looked at a 10-year period between 2001 and 2011 and also found that the number of kills exceeded government sanctioned limits in half of the populations open to hunting.

“The precautionary approach is not being used in BC for grizzlies, and there’s no social license for the hunt,” Artelle says, flatly. The precautionary principle makes simple sense here: in the absence of scientific consensus, the burden of restraint falls on those wanting to take action, or in this case, pull the trigger.

In 2012, Coastal First Nations, an alliance of 14 nations, imposed a ban on sport hunting in their collective territories that stretch from the Sunshine Coast to Haida Gwaii. It’s a unilateral indigenous declaration, but illegitimate in the eyes of the provincial government. According to William Housty, a Heiltsuk activist and director of the science-driven guardian program called Coastwatch, First Nations rangers regularly patrol coastal inlets and valleys, prepared to confront grizzly hunters.

In Northwest Coast native art and mythology, bears symbolize strength and family and are considered to share human traits. Housty acknowledges that, historically, grizzlies have been harvested by First Nations for ceremonial purposes, a fact used by some to accuse Coastal First Nations of hypocrisy. However, says Housty, indigenous practices were in such low numbers that he considers a comparison with modern trophy hunting a joke. “Government doesn’t have a leg to stand on any more, but they still say their science is sound,” Housty says over the phone from Bella Bella, British Columbia. “[Grizzlies] are a species who don’t need to be managed by someone in a shirt and tie in Victoria, and if given a chance, can manage themselves.”

Artelle and his colleagues looked at a 10-year period between 2001 and 2011 and also found that the number of kills exceeded government sanctioned limits in half of the populations open to hunting.

However, decisions by bureaucrats and policy makers are a major influence on the long-term viability of large carnivores like grizzlies. As such, Ursus arctos horribilis is as much a public-relations problem as a scientific one for government. Provincial environment ministry bureaucrats did little to instill public confidence when, in 2000, they suspended now-retired-but-then-senior habitat biologist Dionys de Leeuw for two weeks without pay for publishing a paper that critiqued some of the statistics used to establish grizzly hunting quotas. Nor did the government earn sympathy by guarding its kill data in a five-year court battle with the Raincoast Conservation Foundation. One public opinion survey after another finds British Columbia residents — by some counts more than 80 per cent — are vehemently opposed to hunting grizzlies.

The shooting of apex predators, to most, seems anachronistic, a pursuit that should have been buried with Ernest Hemingway. Even putting aside the idea that grizzly bears have intrinsic value and the right to peacefully exist, you can distill the issue down to a frank economic conclusion against the hunt. There’s mounting evidence that a live bear is worth much more to the province than one that is hunted and killed.

A 2013 study by the US-based Centre for Responsible Tourism examined bear hunting and bear viewing in the Great Bear Rainforest — a 30,000-square-kilometre swath of coastal temperate rainforest extending from the Discovery Islands archipelago, located along the Inside Passage, to southern Alaska — and concluded that bear-viewing companies generated 12 times more in visitor spending than bear hunting operations, and 11 times more in government revenue via taxes, permits and licence fees.

Dean wyatt owns Knight Inlet Lodge, an operation that switched from sport fishing to bear viewing in 1996, and he has since hosted 26,000 visitors from more than 30 countries. Each guest gladly pays as much as $1,000 per day for the chance to view grizzlies along the Glendale River. He does approximately $3 million in business annually.

To do this, Wyatt has to personally spend $20,000 every year to compensate a hunting guide outfitter who would otherwise conduct his annual government-sanctioned hunt in the Glendale. Wyatt explains this is because the fish and wildlife branch of the provincial government favours hunting and fishing over wildlife viewing. “They don’t understand our business,” he says.

Scott Ellis is executive director of the Guide Outfitters Association of BC (GOABC), an organization that represents dozens of hunting guides in British Columbia and has been in the crosshairs of conservationists for years. Over the phone, Ellis says hunters and bear viewers can coexist as long as they’re not chasing bears in the same valley; it is an argument that will never find traction with trophyhunting opponents. Gerald Amos is one such opponent. A Haisla native who led the fight to preserve the Kitlope Valley near Kitimat from logging, he recalls watching hunters shooting grizzlies during the Kitlope River salmon run. He called it about as challenging and fair as “shooting fish in a barrel.”

For most biologists, taking a public stand against the grizzly hunt could kill your career and cost you government contracts. Or, if you suggest that it might actually be sustainable, you risk becoming a pariah among the conservation organizations. Grizzly science is increasingly a grisly business.

Bruce McLellan handles that prickly portfolio for the Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations. A research ecologist who has studied grizzlies in British Columbia for 35 years, he says he avoids the politics of the grizzly hunt as much as possible. Yet he will challenge the science, assumptions and methodology of some of the provincial government’s loudest critics. As example, he takes particular exception to the David Suzuki Foundation’s recent critique, and Kyle Artelle’s SFU study, claiming both are based on “very old information.”

“We know a lot more about grizzly-bear populations now than we did when these policy documents were written,” McLellan says. “I really wish these people would call me up to discuss these issues.”

He sees a much more nuanced picture than the one projected by critics focused on the grizzly hunting issue. As a government biologist, McLellan and Parks Canada colleague John Woods developed a method of estimating bear numbers using DNA from hair, known as genetic mark-recapture, that has been replicated around the world. The province has used the procedure to estimate grizzly numbers for almost 30 areas.

On the research front, McLellan says there are currently three ongoing long-term telemetry projects in British Columbia measuring various aspects of grizzly-bear ecology: including population vital rates, habitat and connectivity. Furthermore, he says there are many wilderness access closures that are at least partially for grizzly-bear conservation.

Putting the ethics of trophy hunting aside, the brouhaha about grizzlies boils down to population science. Counting bears is difficult and expensive work, especially in a province that has grizzlies living across 800,000 square kilometres. As McLellan points out, a single population study done in northern Montana alone, an area one-twentieth the size of British Columbia, cost $4 million.

Dated as it may be, the 1995 Grizzly Bear Conservation Strategy set a high bar for grizzly-bear sustainability that the province struggles to meet, and it hangs over the heads of bureaucrats like a guillotine. Today, the hunting of grizzlies is more a source of provincial shame than anything to stake a Super, Natural BC reputation on. Yet McLellan believes the four to six per cent of all forms of human-caused mortality (HCM) limit currently imposed by the provincial government is sustainable, and perhaps even conservative.

“We will never bridge the gap between some of the public and government stewards due to the biggest issue on this topic, the ethics of grizzly hunting,” McLellan says. “For some people ethically opposed to grizzly-bear hunting, claiming a lack of sustainability has more traction than [saying,] ‘It is simply wrong to hunt grizzly bears.’ Therefore these people will always say that the hunt is unsustainable — they have for 40 years.”

Even putting aside the idea that grizzly bears have intrinsic value and the right to peacefully exist, you can distill the issue down to a frank economic conclusion against the hunt. There’s mounting evidence that a live bear is worth much more to the province than one that is hunted and killed.

When you see a grizzly in the wild, the nasty politics of bear hunting and bear science dissolve in the immediacy and excitement of the moment. Such was the case when my dad, brother and I nearly bumped heads with one years ago. It was the same when I travelled the British Columbia coast for two weeks on a boat with Ian McCallister in the early 90s, some 15 years after my first grizzly encounter back in Kokanee Glacier Park.

In one inlet in particular, which McAllister practically made me swear on a Bible not to name, the primary forests that rose up on both sides were deep and thick. A raven perched on a crooked cedar overhanging the bay nearby and let out a throaty squawk, presumably some sort of broadcast warning that humans were afoot.

We scanned the estuary from the intertidal zone to where it meets the forest fringe of cedar and hemlock trees, festooned with lichen. We quickly spotted the telltale hump of a grizzly bear protruding above the sedges, preoccupied by his morning’s forage. A well-trodden animal trail paralleled a side channel of the river. We followed it. Here and there, the groundcover was disturbed where a bear had recently tilled the earth searching for starchy bulbs of lilies, a favourite springtime staple.

In the mud, perfectly preserved grizzly tracks the size of a basketball were inlaid, at one point, with equally exquisite wolf prints. We followed the grizzly tracks to where they disappeared into the forest, wondering if one day they’d disappear altogether.

Andrew Findlay

Andrew Findlay is an award-winning journalist and photographer with a home base on Vancouver Island. Born and raised in British Columbia, he continues to draw inspiration from the people, places, triumphs and travails of the Canadian West, however he ranges across the globe in pursuit of stories. Andrew’s journalistic interests are many; he enjoys peeling back the complex layers of social, environmental and business issues, but is also inspired by travel and outdoor adventure. Magazine and newspaper assignments have taken him to lands and cultures as diverse as the Great Bear Rainforest of BC, the remote mountains of northwestern Guatemala and the frozen ice hockey ponds of northern India.

Related Stories

Across the Mighty Tundra

One of our editors had the pleasurable task of driving from Nelson to Vancouver. A drive we at the KMC/CMC staff do…

STAND movie hits BC in early May

From our Friends Anthony Bonello of b4apres Media, and Nicolas Teichrob, photographer comes the cinematic premier of…

Creaking Tree String Quartet touring BC

Two time Juno nominees, The Creaking Tree String Quartet are coming to British Columbia to promote there fourth Album.…

Cool New Video by Nelson BC’s Best Western Hotel

The world of the webisode gets funner by the day. This new piece by the local Nelson family that runs the town's Best…

Jumbo Gets the Go Ahead by BC Government

It's been a point of debate in the Kootenays for nearly 20 years. Today it looks like Jumbo Glacier Mountain Resort is…

Grizzly Snooze – The Backstory of a Classic Photo

Alberta resident and mountain lover Andrew Dole happened to be in the right place at the right time to snap this…