For most of its lifespan, the craft of film-based photography always told the truth. But today, in an age of ubiquitous post-production boosting, the ethics around photo manipulation have never been more blurred. Looking to Banff, Pakistan and Australia, past-KMC editor Chantal Tranchemontagne chronicles three photographers who suggest a picture from our digital age is no longer worth a thousand words. It’s worth even more.

Fact: At the 2015 World Press Photo competition, one out of every five images was disqualified in the semi-final round. Too much post-processing, the judges said. Too much manipulation, too much blatant disregard for the truth.

It threw the spotlight on photography — a profession entrusted to tell the truth. The arena of journalism doesn’t always take well to artistic license. But what is the truth? A photographer’s job, after all, is to interpret and relate a moment in time for us. Does it then become dishonest if it’s bent? Or is it just an exercise of vision?

Our three featured photographers are technical, creative and clever, and offer a unique interpretation of what lies beyond the lens. They frame each shot exactly as they want us to see and feel it. They push their perspective, challenge our perception and skillfully blur the line between fact and fiction.

- Ray Collins — The Enigma

- David Kaszlikowski — The Technician

- Paul Zizka — The Romantic

[divider margintop=”20″]

Ray Collins — The Enigma

Three days a week, Ray Collins travels deep into the Appin West coal mine, which is 30 kilometres long and about one kilometre under the surface of the earth. Driving burly, noisy rigs is tough and dirty work, he says, but he likes it anyway. Like most other men born in Bulli, Australia over the last 100 or so years, this 33-year-old was practically born with a headlamp on his cranium and destined to work down under Australia’s Great Diving Range.

When he’s not at the mine, he concentrates on a second job, one that involves studying tide charts, analyzing weather patterns, tracking the trajectory of the sun and hours bobbing in the ocean. Armed with a waterproof camera setup, Collins is one of the most celebrated surf photographers.

This secondary life as a photographer may seem unlikely for a coal miner, but it’s even more improbable for a colour-blind one.

He came to photography late in life after an awkward slip off a platform at the mine caused a bad meniscus tear in his right knee. “Biggest blessing ever,” he says. To fill his down time, he bought a camera — his first — and watched endless online tutorials. As soon as he could swim again, he started shooting ocean life around his home surf in Thirroul, about an hour south of Sydney. Accolades and opportunities swelled: cover shots, prestigious grants, assignment in more than 20 countries with surf gods like Kelly Slater, Eddie “The Predator” Blackwell and Ryan Hipwood. He also published a handsome 184-page hardcover book called Found at Sea and cemented relationships with clients like Patagonia, Red Bull and National Geographic.

[divider margintop=”20″]

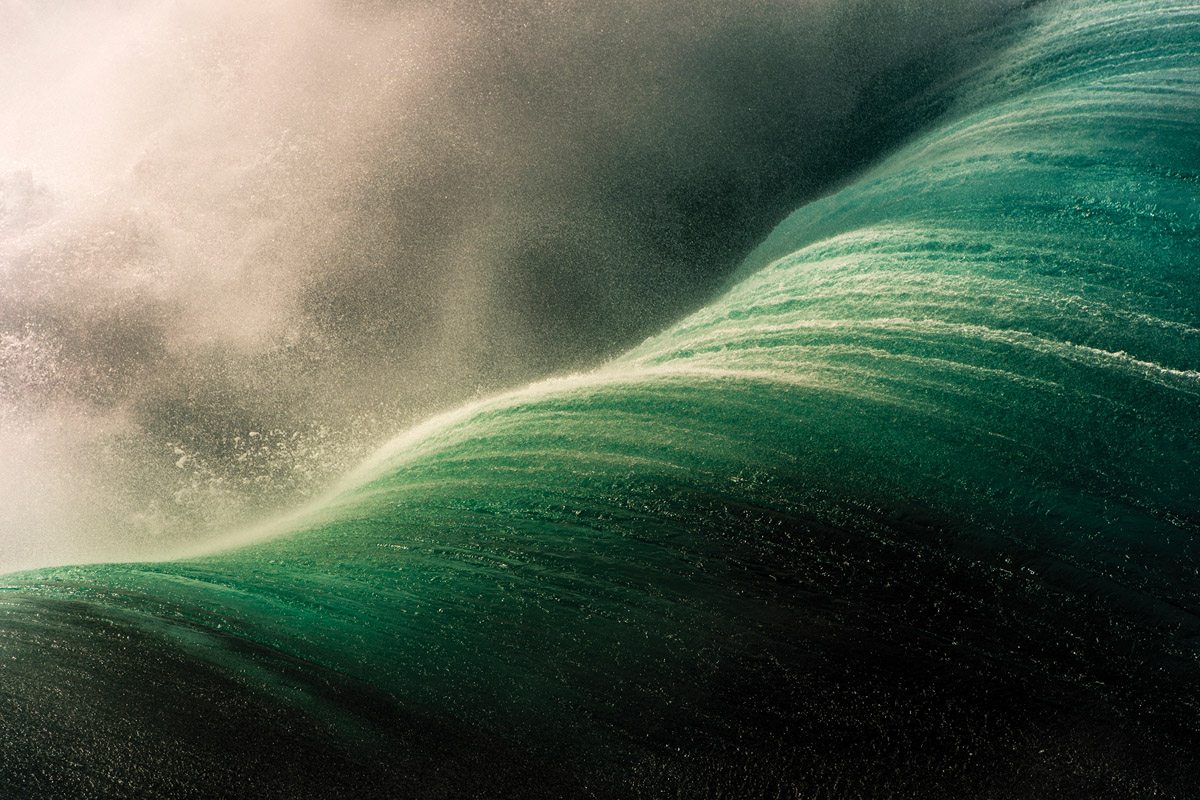

This secondary life as a photographer may seem unlikely for a coal miner, but it’s even more improbable for a colour-blind one. Collins’ inability to perceive differences in colour hasn’t held him back. In fact, it has directly influenced his photography and augmented his technical approach. “Not being able to see differences in colour has forced me to look at composition more than actual saturation,” he says. And that explains why many of his most captivating images are not of surfing pros but instead portraits of waves framed to look like mystical mountains.

As if ripped from a fantasy novel, Collins’ photos are soulful and powerful, and the seasoned photographer knows it. “I work really hard to make that happen,” he says, explaining how he usually sets out before dawn when it’s cold and dark to capture the wakening of perfect light. He often has to stare down cliffs and jump off rock ledges into the unknown. He wears a wetsuit and fins, and carries 20 pounds of camera equipment, which he compares to “swimming with a bag of concrete.” As if this weren’t already challenging enough, Collins goes up against waves over 20 feet high, sharks and other hidden dangers, hoping to freeze the perfect frame of a wave at its crest. “I like the moment before a wave crashes,” he says. “This is when it’s at its angriest and most dynamic.”

Collins admits he’s interpreting the wave as a mountainscape. “Because mountains are in my backyard and in the backdrop of my consciousness, it’s obviously influencing how I frame my seascapes, too.”

“I love this idea of nature imitating nature,” he explains. “It’s so interesting to watch people react to this. They think they’re seeing a solid landmass when it’s really a liquid, ephemeral sculpture that is gone in a split second. The chance to shoot that split second is the reason I get out of bed at four in the morning.”

David Kaszlikowski — The Technician

It’s rare to get a bird’s eye view of the Baltoro Glacier, deep in the Karakoram Range of Pakistan. A few helicopter passengers get the opportunity but only if they’re part of a search-and-rescue team or members of the national army or folks who can swing the $10,000-perhour flight price tag. But David Kaszlikowski found another way to get that unique perspective from up high. He used a drone, a small remote-controlled aircraft.

While working on the 2015 HBO documentary K2: Touching the Sky, the Polish photographer spent more than three weeks on the planet’s longest non-polar glacier. His main allegiance was to the filmmaking process, but that didn’t stop him from taking photos for his personal portfolio.

Given the vastness of the area, he was limited in how much terrain he could survey on foot. “You can’t simply walk around to check things out. You’d be exhausted,” says the 42-year-old. “Plus, there are deep crevasses hidden below thin snow. It can be extremely dangerous.” Every day of the expedition, in his free time, Kaszlikowski scouted unusual ice forms and interesting patterns using a first-generation DJI Phantom 1 drone mounted with a GoPro to fly around Concordia, which is the confluence of the Baltoro and Godwin-Austen glaciers.

He captured otherworldly images of glaciers twisting and turning through the mountains, mesmerizingly monochromatic landscapes, and even of a tucked-away glacial pool in the shadow of K2. “I know I’m playing with perception, and I love engaging someone’s imagination,” he says. “As a photographer, I have the chance to freeze the moment, to catch a fraction of a second from my reality, my vision.” These landscapes had never been seen before and because glaciers are constantly melting, changing and even disappearing, will never be seen in the same way ever again.

and i realized that i wasn’t just changing the composition of the picture. i was changing the whole feel, the whole story.

Drone photography comes naturally to Kaszlikowski. His climbing career — peppered with accomplishments including 10-plus free solos of skyscrapers in Warsaw and 13 big-wall first ascents from Alaska to Mali to Malaysia — along with his work as an adventure photographer, give him the unique skillset for finding fresh perspectives. “I’ve spent months of my life hanging on ropes, sometimes upside down to keep my feet out of the frame, so drone photography and the idea of angles feels very familiar to me,” he explains. “The only difference is that using a drone is less tiring.”

Kaszlikowski is acutely aware that drones have changed the photography landscape and are becoming more common, but he’s not worried. “I know that what is stunning and surprising today is already getting pushed and published so much. I think that at some point, the average person will get bored by the aerial perspective,” he says. “But that’s okay. Photography isn’t all about technology. It’s really about the photographer’s creativity. I have lots of that.”

Paul Zizka — The Romantic

Paul Zizka’s story starts like the story of so many Québécois kids. At 18, he “went out west” to spend one summer working in the Canadian Rockies. Then he came back to the mountains for six more. At the end of his last term as a lodge hand, that fresh-faced boy decided to put down his roots in Banff, Alberta. Now 37, he’s just as full of awe and passion for the area’s wild spaces as the day he first arrived. “It’s just… incredibly magical,” he says. When you cast your eyes on Zizka’s supernatural self-portraits, it becomes clear his work is a deliberate reflection of that sentiment. His images are as intimate as they are inviting. The viewer is summoned into that quiet moment where the awesomeness of the Rocky Mountains has been amplified.

Zizka wasn’t always successful transmitting his sense of wonder through his work. When he started full-time as a photographer in 2009, he says, “The skills just weren’t there” and his images were only okay. “Like a lot of people around here, I started my career by shooting Vermillion Lakes at sunrise. Nothing special,” he says. “But it didn’t take long for me to start looking for the extraordinary and being totally willing to commit more time and energy into finding it.”

and i realized that i wasn’t just changing the composition of the picture. i was changing the whole feel, the whole story.”

His perseverance helped him capture increasingly arresting landscape and adventure images, and attract editorial and commercial work. But in November 2012, he found his most enchanting formula to date: aurora borealis plus mountains plus himself. After struggling to get a well-composed night shot of Vermillion Lakes, he tried a new tack. He set the timer, ran into the frame and snapped the first image in his Aurora series. “Adding the human element changed everything,” he says. “And I realized that I wasn’t just changing the composition of the picture. I was changing the whole feel, the whole story.”

The shot, which he named “The Dreamer,” shows the luminescent northern lights dancing above Mount Rundle — Banff ’s signature peak. Zizka’s silhouette is in the foreground on the frozen lake. The careful construction is layered and impactful. Because he chose to leave out his face, anyone can visualize himself or herself in that time and place. This type of image “makes people realize that these magical places do exists in real life.”

He wants his images to translate into emotional experiences. And that points to his ulterior motive. “I document my relationship with the wilderness because I hope it encourages people to get out there too,” Zizka explains. “When others learn to love it as much as I do, they might want to keep it the way it is, for everyone to enjoy.”

Chantal Tranchemontagne

Chantal was KMC's editor-in-chief for a couple of years while Mitchell Scott worked on other projects. She was also the former editor-in-chief of Magazines Canada. She has close to 15 years of media experience, producing clear and compelling content for print, press, sales, magazines, web, social media and everything in between. She also likes baking.

Related Stories

Saving The Bats of Glacier National Park And Beyond

With a deadly disease creeping westward, scientists and government are throwing a lifeline to the bats of Glacier…

Skiing World Loses a Bright Light: Dave Treadway Perishes in Backcountry Accident

It's with heavy hearts we share the loss of legendary Canadian skier, and our bud, Dave Treadway. Rest in peace,…