As long as an alligator and with the hide of a prehistoric pachyderm, she has lurked the Kootenay River system since before World War I. How a certain super-sized sturgeon is helping scientists in Montana, Idaho and British Columbia understand the very uncertain fate of these deep dinosaurs.

Big fish do weird things to people. And by big fish I mean really big fish. They affect some part of our reptilian brains and account for the manic popularity of television shows like Shark Week, River Monsters and Hillbilly Handfishin’. This prehistoric connection overrides rational thought and amps up our adrenaline levels — which is exactly what happened to me when I first heard about Big Bertha.

I’ve never given a second thought to swimming in Kootenay Lake, unless it’s February, but when Nelson-based fish biologist Sarah Stephenson showed me a photo of the dinosaur she hauled up from the depths near Creston last April, I froze. “That monster lives in the lake?” I asked. She told me not to worry as it was harmless to humans, but this fish was important. In fact, given that its kin are no longer successfully breeding in the wild, this fish could impact the future of its species.

Big Bertha is the nickname of the 10-foot Kootenay white sturgeon that weighs over 350 pounds, roughly the size of a full-grown female alligator. Its age is estimated between 80 and 100 years and it’s the largest and oldest fish of its kind ever caught. Yes, there are larger white sturgeon in the province, but the local population — which exists in the Kootenay River system from Duncan Dam, north of Kaslo, to Kootenay Falls in Montana — is unique because since the last Ice Age they’ve been isolated from the ocean by a natural barrier at Bonnington Falls. In other words, they were corralled 10,000 years before the first hydro dam was ever built.

The white sturgeon’s scientific name is Acipenser transmontanus, which means the “sturgeon over the mountains.”

[one_third]

[/one_third]

[two_third_last]

Like many of the 26 species of sturgeons that have survived since the Paleozoic era, the Kootenay population has been threatened by overfishing and habitat change in the last century. Their dire straits were first noticed in the 1970s when Montana closed its sturgeon fishery, and in 1994, when British Columbia and Idaho followed suit. At one time there were an estimated 7,000 wild adults in Kootenay Lake. Today that number is closer to 1,000. What’s worse: not one is producing offspring.

This is why the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho started an aquaculture program with funding from the Bonneville Power Administration — the American federal agency that markets hydroelectric power in the Pacific Northwest. The Tribe fertilizes sturgeon eggs at a hatchery and 12 to18 months later populates the river system with juveniles. Today there are a myriad of organizations helping out. “We’ve been the lead instigator [of the hatchery program],” says Shawn Young, a fish biologist with the Tribe. “But once the fish are released, monitoring is done by Idaho Fish and Game, Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks, the US Fish and Wildlife Service, and the BC Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations.”

Despite this complex bureaucracy, the aquaculture program seems to be working well: over 220,000 hatchery juveniles have been released into the Kootenay River system since 1990, and 1,000 of those released fish are caught annually as part of the monitoring program. But this doesn’t mean we’re going to see another local sturgeon fishery in the next few years, because the bigger concern is that the current wild adult population is not successfully reproducing. Which is where Big Bertha comes in.

[/two_third_last]

In April 2014, Sarah Stephenson and fellow BC ministry employee Val Evans were in their boat near Creston angling for sturgeon as part of their annual adult sampling program. They are two of only a handful of people in the country who are allowed to do this on Kootenay Lake — the white sturgeon here are federally listed as endangered, so if you try to catch one you face jail time and a huge fine. Evans remembers they hadn’t had much luck in the previous two weeks and were getting frustrated. “Sarah said something like, ‘Just one more cast.’ And I said, ‘What’s the point?’ And then she caught a monster. It was unbelievable! Like a fairytale creature.”

They were using a heavyweight halibut rod, with a 150-pound test line and a baited, barbless circle hook. It took them 40 minutes to reel it in. They had to switch off twice because their arms were so exhausted. “Sturgeon are really powerful,” Stephenson says, “but after tiring out they become super docile, which is great for us scientists.” When they finally got Bertha beside the boat, they realized their onboard crane maxed out at 250 pounds and they were in danger of capsizing. So they slowly made their way to shore and examined the fish just off the beach.

The fish measured 332 centimetres from tip to tail and its skin was about 10 centimetres thick: four times thicker than an elephant’s. They estimated its weight to be over 350 pounds and determined it was a female given its shape and size.

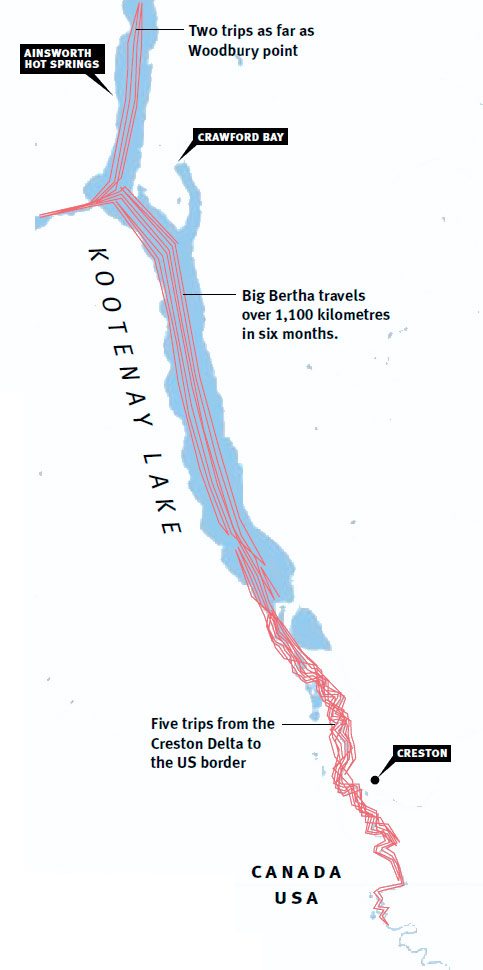

Then, and most importantly, they inserted a sonic tag into the specimen.That tag is crucial because the telemetry buoys set up along the length of Kootenay Lake and upstream in the river have monitored her movements since Stephenson and Evans caught her last April. In the first six months, they discovered she travelled an astounding 255 kilometres from Creston to Balfour to the US border, back to Balfour and then to Woodbury.

What they’re really hoping, though, is that her actions and spawning habits help explain why wild eggs are not surviving through the larval life stage. All Kootenay sturgeon breed near Bonners Ferry, Idaho, at the south end of the lake, but the females do so about every five years and only after they’ve reached an age of 35. Perhaps larval health is being affected by the substrate on which they lay their eggs? Or maybe it’s the water temperature or changing flows from a dam-operated system? More than a few theories are possible, but one thing’s clear: with a little luck, a 10-foot, 350-pound monster named Bertha will help solve the mysteries.

Vince Hempsall

Vince Hempsall lives in the beautiful mountain town of Nelson, British Columbia, where he spends his time rock climbing, backcountry skiing and mountain biking (when not working). He is the editor of Kootenay Mountain Culture Magazine and online editor for the Mountain Culture Group.

Related Stories

Kicking Horse Opens Super Bowl

There's new lifts and area expansion happening all over the Kootenay's these days, check out this press release from…

Life On the ‘Squatch Watch

For millennia, Bigfoot has evaded capture and definitive conclusion. Despite myriad monster hunters, top-secret DNA…

CMC Feature Series – Life On The Line

To the west, a market of 1.5 billion consumers. To the east, the planet’s dirtiest oil. And in the middle, a colossal…

Have You Met The Koots Creatures Yet?

Whimsical creatures are popping up all around the Kootenay region that they're named for. This is why. Story by Louis…

In Through The Trout Door

The baseline of the Kootenay freshwater life cycle is populated by millions of one particularly beautiful yet hardy…