Over the last 20 years, the backcountry has seen a massive spike in use. From sledders to shredders, on any given winter day, we’re out there in the thousands. But how many are actually out there? And why hasn’t that corresponded to a sharp rise in accidents or even deaths? Ryan Stuart looks for answers in the statistical world.

Last winter should have started on a tragic note. “It was a gong show,” remembers Gilles Valade, the executive director of Avalanche Canada based in Revelstoke, British Columbia. After a crappy winter the year before, the 2015-16 season went off early. By Sunday, November 8, more than a metre of snow lay on the ground in the alpine around Rogers Pass in Glacier National Park, British Columbia, and powder-starved backcountry skiers stampeded to the buffet. “There were avalanches going off everywhere,” says Valade. But none was scarier than a size-3.5 slide that swallowed a skier and snowboarder on Bruins Pass, one of the most popular areas in the park. As a matter of pure luck, both emerged unscathed.

That chaotic season opening, as a microcosm, mirrors a contradictory trend: while winter use of the backcountry increased exponentially in the last 20 years, the number of people dying in avalanches remains mostly stable. The reason remains elusive, and the question keeps surfacing, especially after days like November 8, 2015.

Because so little data exists on how many people are actually in the backcountry, statistics backing up the overall claim that users are getting in less trouble also don’t exist. One of the few sources of reliable data is Glacier National Park, where skier visits increased about 50 per cent, or by more than 5,000 skiers, from the winter of 201011 to that of 201516. The anecdotal evidence is even stronger. Valade echoes many longtime locals when he says 20 years ago he was alone touring in Rogers Pass on a typical weekend. Now the parking lots fill even midweek.

There’s a lot of circumstantial evidence, too. According to SnowSports Industries America (SIA), a trade organization, American backcountry-ski-boot sales increased 27 per cent last year and now make up 12 per cent of boot sales overall. No comparative Canadian data exists, and MEC, the country’s largest retailer of backcountry gear, won’t release sales stats. But they say interest in backcountry-related gear has increased every year since 2008. Tellingly, in the last five years, just about every major ski-boot manufacturer started making backcountry-specific models. Valade, for his part, thinks there may be as many as 10 times more users. Further to this, page views on backcountryskiingcanada.com, a website full of route beta, have doubled every year since Brad Steele founded the site in 2006. “Where ski movies used to include a lot of in-resort skiing, now it’s all these wild places,” he says. “Everyone wants a piece of the adventure.”

Newer groups of backcountry users are growing even faster. Snowshoeing is the fastest-growing winter sport according to Outdoor Industry Association, another trade group. And then there’s snowmobiling, or “sledding,” as it’s often called. “Fifteen years ago you saw few mountain sledders,” says Valade. “Now I suspect there are more sledders than skiers in the backcountry.”

It’s clear the backcountry has never been busier. It should follow that deaths from avalanches would increase too, but that’s not what the long-term trends show. In the five years before 2015, in Canada, the average annual fatality rate stood at 9.8 users per season. The five years before, that average was 14.2 per season. And it was higher the five years before that. Comparatively, in Europe, a Swiss Alpine Club study found a reduction in fatalities for ski tourers from 11 per 100,000 between 1984 and 1993 to just four per 100,000 between 2004 and 2013. In the US, the average is 27 avalanche deaths per year, about the same as it was from 2001 to 2006 and only slightly above stats from the late 90s, despite the higher number of participants. SIA estimates there are more than 6 million backcountry skiers; which would put the American death rate at less than 0.5 per 100,000.

In the last 15 years, sledders typically made up less than a third of victims. But, more recently, they may be taking over as the “average” avalanche victim, says Avalanche Canada.

Why the spreading gap between skier traffic and avalanche deaths? Could it be the one upside to global warming? Temperatures just below zero do tend to stabilize the snowpack compared to cold snaps, according to Dr. Pascal Haegeli, a renowned avalanche-risk specialist and assistant professor at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, British Columbia. But he notes milder winters also often mean more rain-on-snow events, which tend to create persistent weak layers. The big picture is global warming could actually mean long dry spells and more intense storms; neither of which encourage a stable snowpack. The climate is likely not doing us any favours.

Could the busyness of the backcountry itself then be a beneficial factor to snow stability? Some users suggest tracks on a slope help break up potential weak layers, and really busy slopes close to ski-area boundaries could be getting safer through skier compaction. But Haegeli is skeptical of this idea, because of the haphazard way recreational skiers travel.

Bottom line: “The backcountry hasn’t changed. It hasn’t gotten safer,” says Avalanche Canada’s Valade. Instead, he figures the lower per-capita death toll is more likely a result of “human factors”—backcountry skiers making better decisions. Much of that credit goes to his own organization, which now has more resources than ever and delivers more products: notably, frequent and focused avalanche bulletins and forecasts.

So are less people getting caught altogether? Very few non-fatal avalanche accidents are reported, so it’s hard to say. Users called in only nine non-fatal avalanches in 2002, and 85 in 2014. But that dropped to zero last winter when Avalanche Canada brought online the Mountain Information Network, a separate tool for sharing observations and incidents that doesn’t record them statistically. “There are no stats to support it, but my gut is saying we’re seeing less people caught in avalanches,” says Karl Klassen, Avalanche Canada’s public avalanche warning service manager. “The accident rate is falling.”

Additionally, those caught are now more likely to survive thanks to better technology, like easier-to-operate transceivers and avalanche air-bag packs; better rescue techniques, like speedier shovelling; and more education—7,000 to 8,000 people now take an introductory avalanche course every year in Canada. However, within the macro positive trend are some micro disturbing anomalies. In the US, January 2016 was the second deadliest in 20 years. In Europe, Switzerland’s Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research says preliminary data suggests that in the last few years avalanche-related deaths increased in step with increases in backcountry traffic. And here in Canada, the death toll jumped to an anomalous 16 last winter. This was largely due to a single incident that killed five snowmobilers at once near McBride, British Columbia, which bumped the five-year trailing average close to 11 per year.

“There are no stats to support it, but my gut is saying we’re seeing less people caught in avalanches.” — Karl Klassen, public avalanche warning service manager at Avalanche Canada

Thirteen of the deaths last winter were sledders, one was a snowshoer and two were backcountry skiers. In the last 15 years, sledders typically made up less than a third of victims. But, more recently, they may be taking over as the “average” avalanche victim, says Avalanche Canada.

That’s because it’s still a young sport and the safety culture is chasing to catch up, according to Curtis Pawliuk, a board member at Avalanche Canada and the owner of Frozen Pirate, a Valemount, British Columbia-based business that provides avalanche courses for snowmobilers. He says, “It’s only since the late 90s that snowmobile technology advanced enough to make mountain sledding a reality.”

Valade admits Avalanche Canada initially focused on skiers with its outreach, and snowmobilers got left behind. Since learning from that lesson, he wants to be more proactive with other emerging groups, like snowshoers. “The worst thing we can do is become complacent,” he says.

Although we might not be able to quantify how avalanche safety has improved, and can only speculate about why, we are clearly tuning in and gearing up for safer play these days. It’s definitely no less tempting to dive right in, but with a little forethought, we appear to be coming home in better shape than ever. Let’s keep up that trend.

Ryan Stuart

Ryan Stuart has been fascinated by the natural world since he was a kid, and he’s now sharing this interest through his freelance writing, which he does from Comox on Vancouver Island, British Columbia.

Related Stories

New Backcountry Legislation May Threaten Skiers

Mark Hartley drops in on Mt. Fey. Photo: Isaac Kamink This comes from one our contributors, Mark Hartley. Mark's…

Selkirk Wilderness A Skiers Shangri-La

Over the years the KMC team has been lucky enough to visit the utopian state of Meadow Creek, as guests of Selkirk…

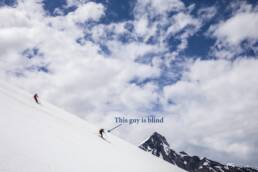

Tyson Rettie is taking blind people backcountry skiing. This is how.

With his Braille Mountain Initiative, Tyson Rettie is introducing visually impaired skiers to the backcountry. By Ryan…

Mount Carlyle Backcountry Lodge

Our friends at Mount Carlyle Backcountry Lodge have a few spots open. Read about their iconic leader the Bald Bomber…

Skiing World Loses a Bright Light: Dave Treadway Perishes in Backcountry Accident

It's with heavy hearts we share the loss of legendary Canadian skier, and our bud, Dave Treadway. Rest in peace,…