International ski superstars and humble local shredders: Pemberton-based writer Lisa Richardson grabs her shovel and follows four skiers out into their chosen summertime fields, where deep dreams turn to dirt.

Farm photography and portraiture by Jordan Manley

Mark Abma was 18 when he first moved to Whistler from Langley, a British Columbian kid with a fantasy about living in a van and skiing all day. “I lived on a futon in a living room of a one-bedroom suite with two other girls and a crazy cat for $200 a month, eating rice with cream of mushroom soup as my go-to meal,” says Abma. “Now I’m so particular about my diet, I’m in awe of how I survived.”

Mark Abma was 18 when he first moved to Whistler from Langley, a British Columbian kid with a fantasy about living in a van and skiing all day. “I lived on a futon in a living room of a one-bedroom suite with two other girls and a crazy cat for $200 a month, eating rice with cream of mushroom soup as my go-to meal,” says Abma. “Now I’m so particular about my diet, I’m in awe of how I survived.”

Over a decade later, Abma is freeskiing’s favourite hippie, a biodiesel-hoarding bro who’s comfortable enough in his own radness to practice yoga, Instagram about enjoying a sunset with his fiancée, former-Olympian Kristi Richards, and start an environmental foundation called 1STEP, which encourages winter playing sustainably, all the while stomping gnarly Alaskan ridgelines and shooting segments for MSP and Salomon FreeskiTV.

In an average winter, he churns 14.5 tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere through air travel alone — accounting for almost half of his calculated carbon footprint, which he offsets through the company Native Energy — so when he comes home, he wants to get grounded, and fast. “Balance is something I’m striving to attain right now, healthwise, workwise,” he says, “[because] so often I’m bouncing from place to place.”

This is part of the reason why, in 2008, he chose to make Pemberton, British Columbia, his home base. “I was looking for a slower pace of life,” he explains. “And the farming sold me. The ability to grow so much food. I wanted to be closer to my food.” He and Richards started with a couple of raised beds, then dug up the entire front yard and replaced it with a 900-square-foot garden; the lawn was repurposed as a sod roof to insulate the backyard sauna. They ran drip lines through the garden so the growing would continue while they travelled, built a root cellar, kept chickens, squeezed a storage container full of waste vegetable oil into a corner, and this summer they plan to build a greenhouse and start some fruit trees.

Abma doesn’t know what the turning point was, where the kid eating cream of mushroom soup became the guy who juices, makes his own granola and wonders how much quinoa he could grow on his Pemberton lot. “I’m not sure if there’s one pivotal moment,” he says. “It’s so interesting how my path at the grocery store has changed: I circumnavigate the aisles now: I barely go down the middle aisles where all the packaged, processed goods are. Right now, I’m just trying as much as possible to eat real food. And the garden gets better and better every year.”

Ian Mcintosh comes back down to earth, literally, about 70 times a summer. He averages as many as 70 jumps per skydiving season and now uses wingsuits when he flies.

Still, the 31-year-old Pemberton-based pro skier sees nothing incongruous in an adrenaline-addicted athlete spending a couple of hours weeding the garden or making pasta sauce from an awesome backyard tomato harvest. “Being able to grow some of your own food is badass,” he says, shrugging off any concern that his hard-charging persona might be compromised when people find out he likes to garden.

“Every young farmer I know right now is in it because they want to have a positive influence on their community, or because they want to raise their kids in a good way, or because they just love growing.”

— Delaney Zayac

“Being an athlete means eating healthy, training hard and staying fit. Plus, when you spend a lot of time playing out in nature you gain a deeper respect for the natural world,” he observes. “Why would I want to eat a tasteless tomato that comes from some far-off place and has been sprayed with poison and genetically altered, when I can grow one in my own yard? Commercial shipping accounts for more air pollution then all the cars and planes on the planet, so eating delicious local healthy food in my mind has a much stronger positive impact on our environment than driving a hybrid car.”

A small-town kid who grew up in BC’s Kootenay region, McIntosh’s awakening was triggered when he bought a house in Pemberton five years ago, and friends who’d grown up on an organic farm initiated a garden, opening his eyes to growing your own produce. Now, he spends the summer eating out of his garden and has a freezer full of basil and tomato sauce, alongside half a local grass-fed cow.

The North Face-sponsored athlete, who spent the winter filming with TGR and Sherpas Cinema, is living a professional dream right now and fully aware of that privilege. “It’s a fun and exciting lifestyle, and it won’t last forever so I’ve got to take advantage as much as possible,” he says, eschewing guilt over his carbon footprint for a more productive stance. “Stopping everything we do, including travelling or using a heli to access some unreal Alaskan line, would be moving backwards,” he says. “I’m no environmentalist, but I spend a lot of time in nature and that makes me want to protect it. We don’t make big change staying at home and doing nothing. Instead doing what you can in life to make a difference and trying to make conscious decisions every day, whether that’s eating local or carpooling to the ski hill or riding your bike to the store, whatever it may be, it all has a positive impact.”

In an average winter, Abma churns 14.5 tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere through air travel alone—accounting for almost half of his calculated carbon footprint, which he offsets through the company native energy—so when he comes home, he wants to get grounded, and fast.

While Abma and Mcintosh get down and dirty in a backyard garden as part of a healthy lifestyle, JD Hare has taken it a step further, hoping to turn his seven-acre patch of Pemberton earth into a farm that will sustain his family and, eventually, leave him his winters free to play.

A self-propelled mountaineer-style skier and former Patagonia ambassador, Hare spent his 20s avoiding the pro circuit of Las Lenas-Whistler-Verbier, seeking new lines deep in the countries of Georgia and Kyrgyzstan or descents throughout the Coast Mountains’ Waddington and Tantalus Ranges.

An old-school-style skier, Hare doesn’t self-identify as a hippie or count his carbon footprint. In fact, when he bought seven acres in Pemberton in 2001, he envisioned a future more as a property developer than organic farmer.

But the Agricultural Land Commission wasn’t letting anyone pull farmland out of protected status, Squamish was beginning to boom, and Pemberton and Whistler were awash in new condos. It was the throwaway remark “we can’t all grow blueberries,” from another frustrated landowner who couldn’t subdivide, that stuck in Hare’s mind.

In spring 2009, waking up from surgery with a six-inch post screwed into his repaired femur, snapped while skiing in McConkey’s Trees on Whistler Mountain, Hare, who’d already broken an ankle, a tibia-fibula and blown an ACL skiing, announced to his wife and two-year-old son, “We’re going to become blueberry farmers.”

Three things had happened since that early remark that suddenly made agriculture seem viable as a career path to Hare. People’s awareness about food was growing. The rise of farmers markets meant a grower could sell directly to the consumer, and social media put marketing power in the grower’s hands, too. “When I’d grown up,” Hare admits, “farming wasn’t really a viable career. It always seemed like something for losers.” Now he’s betting everything on the success of 5,000 organic blueberry bushes.

He started farming from scratch, straight out of surgery, crutching around his property in soil that, by sheer good luck, proved to be near-perfect for blueberries. Four years went by while he obsessed, cleared land, built bridges and barns, planted, borrowed money, worked as a carpenter, raised a family and squeezed in a handful of epic ski adventures, before Hare’s Family Farm offered its first harvest at Sea-to-Sky farmers markets.

“Being able to grow some of your own food is badass,” says Mcintosh, shrugging off any concern that his hard-charging persona might be compromised when people find out he likes to garden.

The venture is no hobby farm. It’s a 100 per cent commitment from someone who dangled at the sharp-end of enough ropes to know what commitment means. “I’m a carpenter and I still have to keep that going until this starts to pay for itself, but ultimately this is what I would do,” he says. “Sponsors paid me to ski for 10 years, and I’m so grateful. Now I have a wife, a child and a shitload  of farm debt. But you don’t have to manage a hedge fund to pay your bills. I feel really proud to be an organic farmer. I think that farming is one of those few really decent, noble ways to make a living. And basically, I’ve come to terms with the fact that I spend my time here — building the farm.” A love of nature and a self-reliant streak help turn a pro skier into a farmer, but a willingess to bust your ass is mandatory too.

of farm debt. But you don’t have to manage a hedge fund to pay your bills. I feel really proud to be an organic farmer. I think that farming is one of those few really decent, noble ways to make a living. And basically, I’ve come to terms with the fact that I spend my time here — building the farm.” A love of nature and a self-reliant streak help turn a pro skier into a farmer, but a willingess to bust your ass is mandatory too.

That’s where Hare has a good role model in Delaney Zayac, a Faction Skis rider who spends his winters probing the backcountry around Pemberton with a crew of sled-hards and his summers running an organic farm with his wife and kids. Going into its fifth year, Icecap Organics has 10 acres under cultivation, selling partially by harvest box to 100 subscribers and partially direct to consumers at farmers markets. Their Pemberton location was chosen for three reasons: good growing conditions, a proximity to Vancouver and the mountains.

Still, despite their growing momentum and the surge of keen local greenthumbs and farmers, Zayac isn’t sure we’re on the cusp of a genuine back-to-the-land renaissance. “Right now I see a lot of people getting into it because they like the idea of it, or the lifestyle,” he explains. “That is positive, but we aren’t seeing a big influx of young farmers getting into it for the money, because there isn’t a lot of money to be made. Every young farmer I know right now is in it because they want to have a positive influence on their community, or because they want to raise their kids in a good way, or because they just love growing. The big rush into farming will happen when gas and water and land and resources in general make the current industrial food system financially illogical. Right now some of the biggest food crops grown are grown at a loss, subsidized by tax dollars and essentially grown from fossil fuels. The current model is unsustainable. When it collapses, then we will see young people really get into farming.”

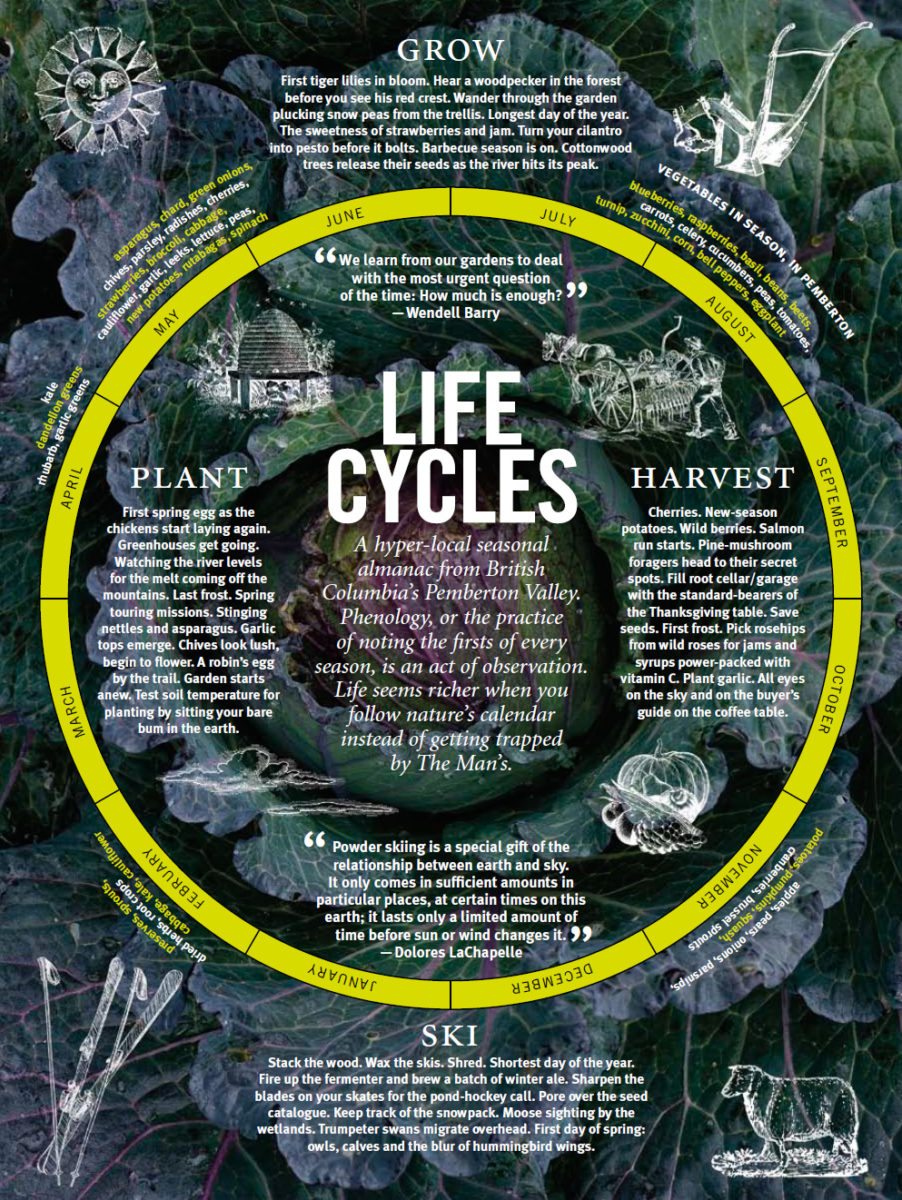

Until then, it might be the health-conscious, balance-seeking, real-food eating skiers who lead the way. After all, when you chase the seasons and spend your days watching the sky and barometric charts to see what kind of systems are blowing your way, there’s a natural rhythm to the year. It divides quite perfectly into four seasons: planting, growing, harvesting, skiing. One simply leads into the next.

Lisa Richardson

Lisa is a lifestyle and ski journalist. She has contributed to a host of publications and outlets including an anthology of ski-writing Skiing The Edge, CBC radio, Pique newsmagazine, www.thetyee.ca, the Vancouver Sun, the National Post, Whistler the Magazine, SBC Skier, Freeskier and The Ski Journal.

Related Stories

Merry Christmas People

We here at Kootenay Mountain Culture Magazine would like to put out a big giant snow filled hug to everyone who's been…

Montana’s Barstool Race Turns 40

It's time to get stooled! Montana’s Barstool Race Celebrates 40 Years of downhill drinking. By Clare Menzel It began…

Sternwheelers of Kootenay Lake

Our Art Director loves his history. He recently found this very comprehensive site exploring the sternwheelers of…

Greg Hill And His Quest for 2MiL

Check out this video of Revelstoke mega ascender, Greg Hill on his quest to shag 2 million vertical feet in one year.…

Greg Hill On His Way to 2 Million

Revelstoke, BC guide and backcountry goat, Greg Hill, recently topped two million vertical feet in one year. Which is…

Splitfest Thank You

In a world fueled by social media and laden with hyperbole, it’s often easy to get caught up in the biggest, baddest,…