One of the Purcell Mountains’ most gruelling and historically significant multi-day hiking routes gets some love. By Dave Quinn.

In the early days of European settlement, exploration of the Kootenays was limited to the handful of established First Nations’ trails that unlocked the vast, untouched wilderness. These routes formed the lifelines of a fledgling colonization that would change the region forever. The Earl Grey Pass Trail, which traverses over a 2,256-metre pass in the Central Purcells to link East and West Kootenay, is one of the few historic routes not replaced by a road. It remains one of the region’s premier wilderness, adventure experiences.

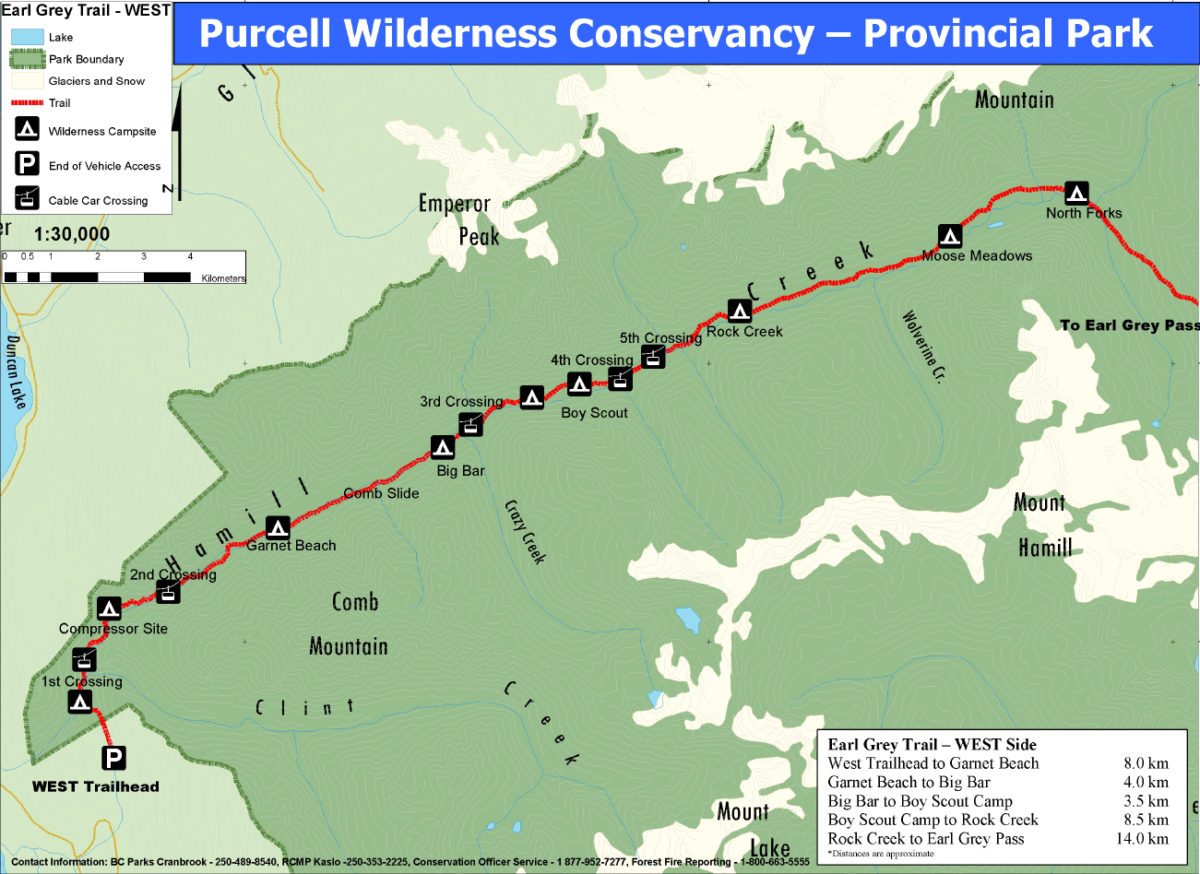

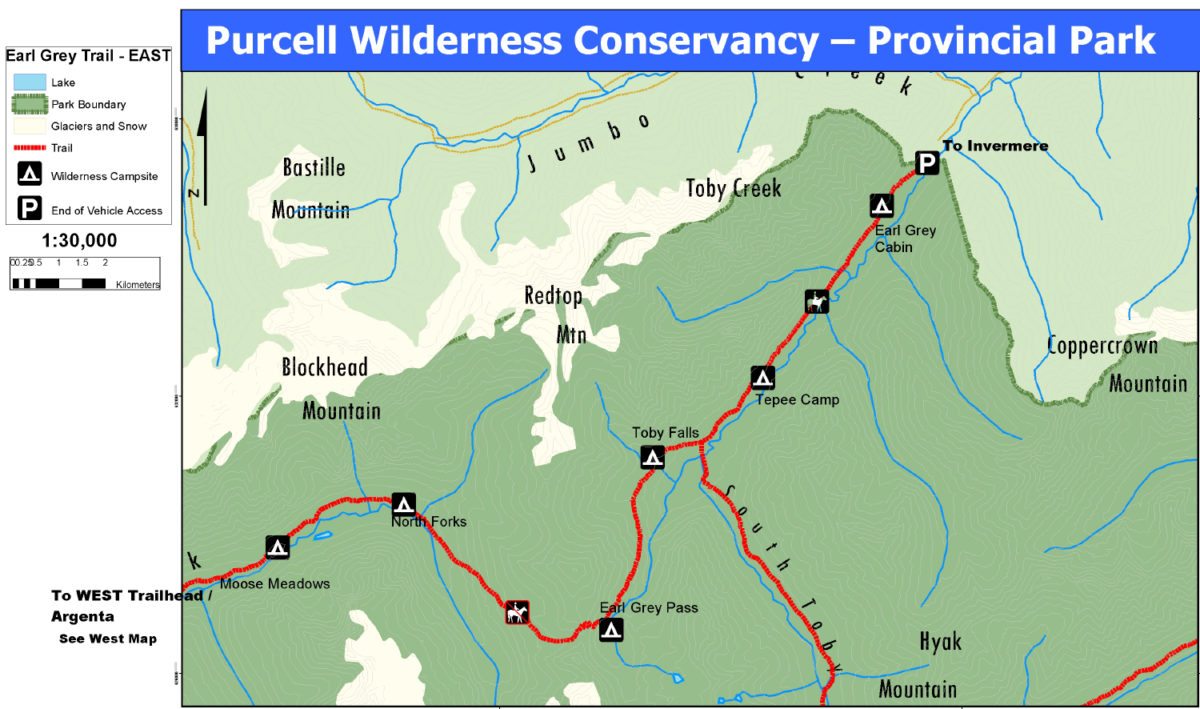

The trail begins southwest of Invermere and travels 61 kilometres west to Argenta. Over the years, it’s been rerouted around avalanche debris and blowdown, boardwalks were built along steeper sections, and, cable cars were placed over dangerous creek crossings. And this summer, to celebrate Canada’s anniversary, Earl Grey is getting a special upgrade. Thanks to funding from the Canada 150 Program, Columbia Basin Trust and the Regional District, recent washouts will be repaired, as will damaged cable cars in Hammill Creek. Interpretive signage will also be installed to explain traditional Ktunaxa Nation knowledge of the route, along with other historical highlights.

Even with these upgrades, which will be done by BC Parks and the Kaslo and District Community Forest Society Youth Crew, the trail is a grind. It’s full of runoff debris, head-high stinging nettle, and other surprises, so hikers who complete it earn substantial backcountry cred. It’s hard to imagine one cow, let alone a whole herd, travelling this trail and arriving intact at the other end. But that’s exactly what used to happen. Here’s a look at the story behind of one of the Kootenays’ most significant byways.

The Earl Grey Pass Trail began as a well-worn, hoof-and-claw path that showed the way to Ktunaxa hunters and traders. They in turn guided early miners across the Purcells, and the trail was expanded to allow horse travel in the Kootenay mining boom of the late 1800s. The route was known as the “Beef Trail” in the early days, as cattle were driven across from the ranches in the east to feed hungry miners in the west.

The region saw its first brush with fame in 1908 when Albert Henry George Grey, Canada’s ninth Governor General and the fourth Earl of Grey, visited and fell in love with it. That summer he travelled on horseback up Toby Creek from Invermere, through the ancient forests of Hammill Creek, to the mining settlement of Argenta.

So stoked was he with the forests, game, glaciers, and towering peaks of the Central Purcells, he had a family cabin built on Toby Creek a year later. Governor General Grey even wrote to then Premier of British Columbia, Richard McBride, making the case to set the region aside as a national park. The proposal did not bear fruit, however, and for the next five decades the still remote, Central Purcells were visited by climbers, prospectors, hunters and trappers. That changed when Toby Creek’s Mineral King Mine, first staked in 1898, was substantially developed in the 1950s.

This development, along with an explosion of forestry roads into the heart of the Purcells, prompted the Invermere Rod and Gun Club along with Argenta hippies to push for the protection of the remaining wilderness. In the early 70s, Federal funds were received via the Opportunities for Youth project to reroute the trail past burned-over areas. Invermere resident Pat Bavin lead the project in 1972. “In July of that year, we took a 10-horse, pack train of dried food up to the Toby Glacier outwash, and worked for 10 days on, out for four, all the way through to September,” he says. “Restoring the trail…was quite a challenge since it was totally overgrown with numerous avalanche debris zones.”

Bavin’s crew also mapped the headwaters of Toby Creek and created a master plan for a future, alpine-protected area.

Finally, in 1974, after a first-of-its-kind, grassroots conservation effort that saw hunters and trappers united with hippy tree-huggers, an Order-in-Council literally stopped bulldozers in their tracks with the creation of the Purcell Wilderness Conservancy. The Earl Grey Pass Trail traverses its northern limits.

Hikers will still find Earl Grey’s family cabin perched at the edge of a massive avalanche path, looking west past the dramatic Pharoah Peaks to the headwaters of Toby Creek. The intervening century has left the log structure in a ruinous state, although, miraculously, much of the roof still remains. A stone hearth welcomes. Bits of beds and furniture are still visible through a mountain of packrat middens. Behind it lies the remains of an outhouse and what must have been either a log barn or servant’s quarters, or both. The essence and the romance of the wild Purcells are still strong here, carried on by the very sense of discovery and awe by the trail’s early explorers.

For more information about the Earl Grey Pass Trail, log on to the provincial government park’s website.

Dave Quinn

Born in Cranbrook, British Columbia, Dave is a wildlife biologist, educator, wilderness guide, writer and photographer whose work is driven by his passion for wilderness and wild spaces. His work with endangered mountain caribou and badgers, threatened fisher and grizzly, as well as lynx and other species has helped shape his understanding of the Kootenay backcountry and its wildlife, and help shape his efforts to protect what remains. His writing and photography has helped fill the pages of publications such as British Columbia Magazine, Westworld, the Financial Post, Backcountry, Adventure Kayak, as well as the Patagonia and MEC catalogs.

Related Stories

Life Cycles Premiere in Trail and Nelson

Oh great goodness, the wait is going to be worth it. Rossland based filmmakers, Derek Frankowski and Ryan Gibb, coupled…

Where The Trail Ends Online Premeire

It's no secret Nelson, BC's Freeride Entertainment is one of the most prolific production houses in the world when it…

Powderwhore’s “Breaking Trail” Trailer 2011

Powderwhore Productions presents, Breaking Trail. This epic backcountry adventure is all about earning your turns and…

91 Octane – $10,000 Season Pass

"With a 125 years of skiing experience 91 octane presented by Shreddy Times release their teaser $10,000 season pass.…

New Mountain Bike Trail at Island Lake Lodge Opens Today

After four years of construction, the Lazy Lizard Trail at Island Lake Lodge in Fernie, British Columbia, opens today.…

Win a Season’s Pass to Red Mountain Resort

Red Mountain Resort in Rossland, BC, is one of our favourite places to shred. And it's that much better when you win a…