Signed between Canada and the United States in 1964, the Columbia River Treaty might by one of the most important land-use agreements in the history of the two nations. The consequences of its renegotiation are very real. CBC journalist Bob Keating examines the history and next steps of the colossal contract.

I met Christopher Swain 15 years ago on the shores of Columbia Lake at Canal Flats where the Columbia River begins its 2,000-kilometre journey to the Pacific Ocean. The New Yorker was 34 then, quick with a smile and eager to chat about the improbable journey ahead of him. He struck me as one of those larger-than-life Americans willing to embark on a crazy adventure just to be the first to do it, make a larger point, or as it turns out, launch a career. I was there doing the very Canadian thing of witnessing something big and recording it for the CBC, a little in awe of the ballsy American.

Swain stood in one of those full-body triathlon swimsuits only serious swimmers wear. A hundred or so kids from Martin Morigeau Elementary School in Canal Flats had the morning off to cheer him on at the outset of his mammoth swim from interior British Columbia to the Pacific. The kids had all been given clear plastic cups, and at the urging of their teachers, did something that alarmed me greatly. They dipped those cups down into a small, spring-fed creek that bubbles into Columbia Lake, and after a boisterous countdown, took a big gulp. Christopher Swain did the same.

No bacteria-killing chemicals or filtration necessary: the Columbia’s origins were as pure as the dreams of those elementary students. Swain didn’t know it then, but by the time he reached the mighty river’s mouth at Astoria, Oregon, 165 swimming days later, most reasonable people wouldn’t let their kids wade into the toxic stew the river turns into, let alone drink from it. Swain’s swim would take him past the outflow of pulp mills and lead smelters, the toxic pesticides of industrial agriculture and the sewage of towns and cities.

Just in case he had any designs on further gulps, the Columbia also meanders by Hanford, Washington, the western world’s most contaminated nuclear-waste dumping ground. The Columbia Swain drank so eagerly from would eventually give him seven ear infections, four respiratory infections and countless skin rashes. Twice his lymph nodes swelled to the size of Ping-Pong balls. “Bear in mind, I’m rinsing my mouth out and gargling with a hydrogen peroxide solution every 20 minutes before I took a sip of water or bite of a power bar,” he would say in a later interview.

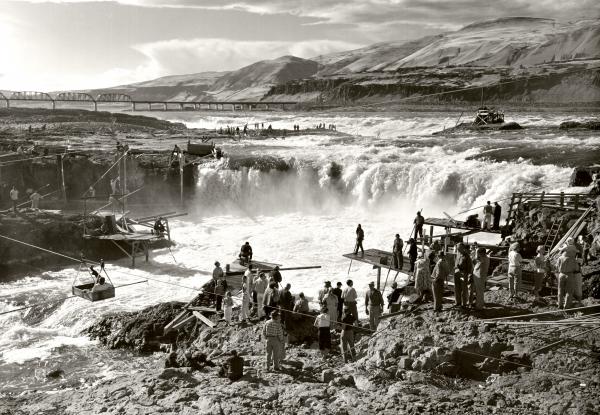

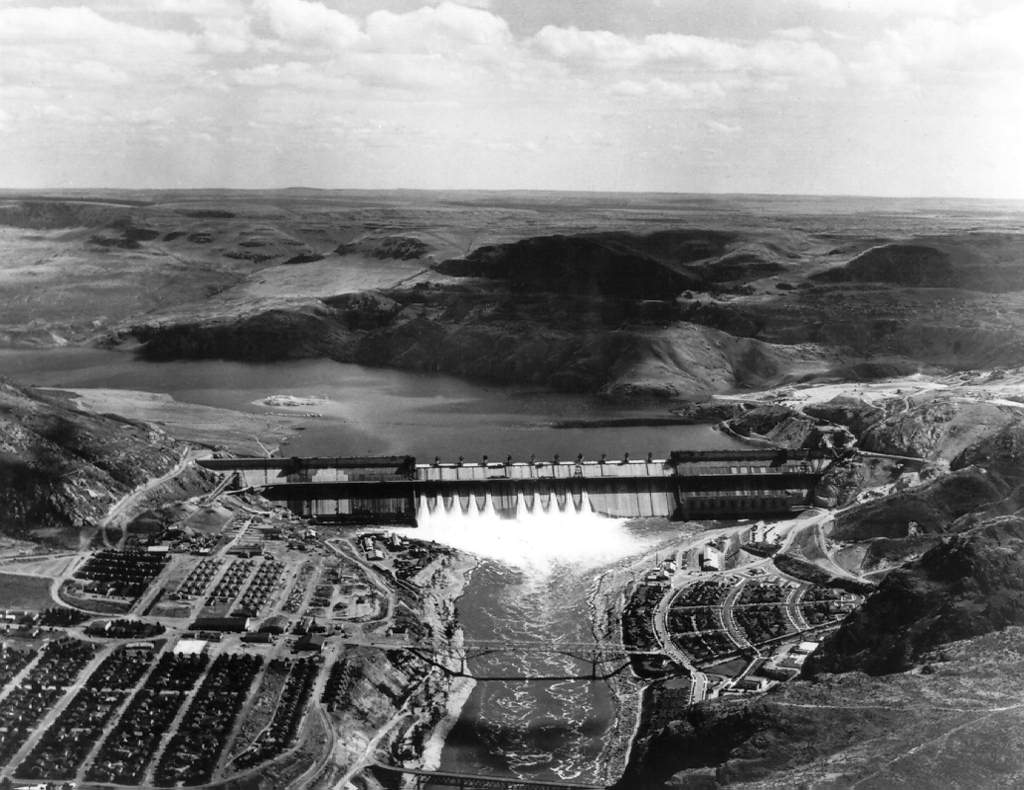

Of course, Swain couldn’t swim the river without numerous portages. The Columbia is one of the most dammed river systems on the planet. There are 14 on the main stem of the Columbia alone—three of those in Canada—backing up the second largest North American river to drain into the Pacific (the Yukon River is the largest) after collecting runoff from a basin slightly larger than France. Of the over 60 dams in the Columbia River watershed, the four dams that reshaped the Kootenay landscape were built after Canada and the United States signed the Columbia River Treaty in 1964: British Columbia’s Duncan, Mica and Hugh Keenleyside dams, as well as Montana’s Libby Dam. The treaty flooded 110,000 hectares of farmland and forest, essentially turning southeastern British Columbia into a giant holding tank, profoundly changing the Kootenays forever. And now the Columbia River Treaty is up for renegotiation for the first time in over 50 years.

Under the current treaty’s terms, the Americans hold great sway over water levels thousands of kilometres to their north. It is arguably the most important document ever signed in southern British Columbia, surely the most important to the Kootenays. And now that it is up for renegotiation, there is almost as much at stake as there was a half century ago.

To download a PDF of the “Dammed & Determined” article as it appeared in Kootenay Mountain Culture magazine, click here:

Dammed-and-Determined-KMC31

We are blessed with a seemingly endless supply of fresh water in the Kootenays, making it easy to underestimate the value of a resource locked in glaciers and yearly snowmelt. Ask a Californian what water is worth. Or look to the once-mighty Colorado River—which didn’t even reach its terminus at the Sea of Cortez between 1998 and 2014—for proof of what happens when something so valuable is poorly managed.

In the first round of negotiations, the Kootenays lost hundreds of kilometres of valley bottom and surrendered control of water levels in its own backyard. The Columbia River Treaty was the greatest sacrifice ever made on behalf of the people of the Kootenays. It’s also an audacious engineering feat that will likely never be matched again by a western democracy. Only China’s Three Gorges Dam project rivals it. In upcoming negotiations that could last up to a decade, the region has the opportunity to regain control of its most valuable resource: water.

AMERICAN VICE PRESIDENT Lyndon Johnson was a lanky Texan looking for an easy win. Beloved President John Kennedy had just been assassinated and Americans didn’t really know or trust Johnson, who had the gall to be sworn in on Air Force One before the country could properly mourn. Johnson made his first foreign trip to British Columbia to sign the Columbia River Treaty, setting into motion an engineering project as ambitious as any infrastructure initiative outlined in Franklin D. Roosevelt’s now infamous New Deal.

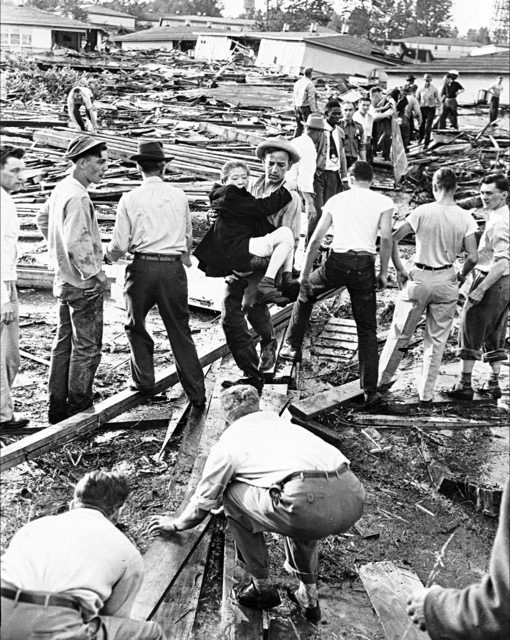

Three new dams, and an option for a fourth, were built on the Columbia and brought the mighty waterway to heel. Aside from generating power, the dams prevented catastrophic flooding, such as the 1948 flood, when anywhere from 16 to 50 people (death was less of a recordable event back then) died in a chaotic evacuation. The floods rendered entire towns in Canada and the US uninhabitable. Floods to that extreme haven’t happened since.

The more water the dams backed up, the more the money flowed. The new dams made utility companies, governments and individuals rich in hydroelectric money, adding fuel to the fire of the postwar dream. To this day, provincial and state governments, through their utilities, make so much money it is impossible to calculate. The United States pays Canada $100 to $300 million a year as compensation. Known as the “Canadian Entitlement,” it’s chump change compared to the hydroelectric profits governments receive from the treaty dams every year. Almost half of British Columbia’s electricity comes from these dams, with the province selling the excess.

In the first round of negotiations, the Kootenays lost hundreds of kilometres of valley bottom and surrendered control of water levels in its own backyard. The Columbia River Treaty was the greatest sacrifice ever made on behalf of the people of the Kootenays. It’s also an audacious engineering feat that will likely never be matched again by a western democracy.

Hydroelectric power is also relatively carbon-free compared to other energy sources and has the added advantage of being generated when it’s needed or when the market pays highest, unlike wind and solar, which only generate when the resource cooperates. The treaty dams have made British Columbia wealthy in the way oil has made Alberta wealthy. They have also turned entire communities into beggars.

First Nations, in particular, were ignored completely when the Columbia River Treaty was negotiated in the 1950s and when the dams were built after that. The Canadian government went so far as to strike the Sinixt people from the Indian Act, declaring them officially extinct in 1956, conspicuously close to the period of time the government was beginning to make plans to flood the Canadian portion of their traditional territory.

The four treaty dams did not choke off the salmon local First Nations cultures were based on, that was the Grand Coulee dam, completed in central Washington in 1941—a New Deal colossus President Franklin D. Roosevelt took personal interest in. The Grand Coulee backed up the Columbia from central Washington to the Canadian border and the giant reservoir it created named was after him.

The treaty dams followed the development of the Grand Coulee dam, creating their own necklace of reservoirs on both sides of the border and ensuring once plentiful steelhead, chinook, coho and sockeye runs would never return. An already staggered people fell into abject poverty. “Even today the lands upriver from the Coulee Dam are some of the most depressed areas in the United States, on reservation or off reservation,” says Michael Marchand, chairman of the Washington-based Colville Confederated Tribes. Marchand talks to me on the steps of the Nelson, British Columbia, courthouse where he’s attending an improbable case. The Sinixt people, declared by the federal government to be extinct 60 years ago, are trying to prove in court they are, in fact, still a people with aboriginal rights in Canada.

Marchand’s grandfather was a Sinixt leader and spear fisherman at what is now Kettle Falls, Washington, where the fishery was so lucrative it drew native traders from all over the continent—until the dams were built. “It really destroyed a way of life,” he laments. “We used to have 5,000 fishermen gathered at Kettle Falls. It was a major trade centre. They’ve found artifacts from the Atlantic Ocean, Gulf of Mexico, all over North America; they came to trade for 10,000 years.”

Farmers and other settlers were also devastated by the creation of reservoirs where there once flowed a river. More than 2,000 people in British Columbia alone were moved to higher ground, their homes and farms burned to make way for the oncoming water. The governments of the day paid them little more attention than they did First Nations. The Arrow Lakes valley used to be the third most fertile in the province, after the Fraser and Okanagan, a lush, idyllic place with farms, apple orchards, and wild grasslands. Now it’s underwater. There are scatterings of people living on its shores in resettlement communities, but not many.

Duncan Lake, Koocanusa and the Kinbasket Reservoirs are even less inhabited. The mountains that rise out of the water are spectacular as any in southern British Columbia. The reservoirs created by the dams somehow discourage exploration and settlement. This is not necessarily a coincidence of geography or history. Why set down roots in a place that is seasonally filled and drained like a bathtub? A bathtub your own government has limited control over. You have absolutely none.

“In general, I’m not sure people understand both what this region possesses and what this region lost in the first iteration of the treaty.” –Eileen Delahanty Pearkes

THE TREATY HAS NO END DATE but either country could have terminated it in 2024 provided 10 years notice was given. In 2014, neither side opted to do that. Provincial, federal and state governments on both sides of the border have no interest in ending a treaty that has serviced them so well. Canada and the US have served notice that they would like to update the treaty to meet the needs of two countries in a new century. They refer to it as “tinkering” or “modernizing” the treaty, a somewhat nebulous reference since no treaty like this exists between two nations anywhere else in the world. Further to that, there surely hasn’t been one revisited half a century later.

“There’s so many questions, I feel like I’m watching a game of poker and waiting for someone to lay a card down,” says Eileen Delehanty Pearkes, a Nelson-based activist and writer who has just finished a book on the treaty called A River Captured. “In general, I’m not sure people understand both what this region possesses and what this region lost in the first iteration of the treaty.” The impacts of a renegotiated agreement can only be guessed at, but just like the first time around, the Kootenays have a tremendous amount to lose—control over its water. British Columbia is choosing its negotiating team and the United States is not that far yet. There are no dates set or even firm rules about what is on the table when talks start. “I think talks will begin when the US has developed a position that it believes will potentially bring them more benefits,” says British Columbia Energy Minister Bill Bennett, whose ministry has taken the lead in treaty negotiations. “BC has already, in 2014, spelled out our interests. We have received one very brief statement from the State Department indicating they might like to sit down, but no follow-up and no formal engagement at this time.”

The treaty dams followed the development of the Grand Coulee dam, creating their own necklace of reservoirs on both sides of the border and ensuring once plentiful steelhead, chinook, coho and sockeye runs would never return.

Flood control will remain the defining interest, with power generation right behind it: the two main benefits the treaty has provided. First Nations are adamant they won’t be a witness to their own destruction anymore. They have already led a heroic effort to get Columbia salmon back to the Okanagan Valley and vow to see them return to the upper Columbia. They want the return of salmon as a priority in any new deal. That alone has implications that would make both biologists’ and bankers’ heads hurt.

Residents on the edge of reservoirs want more stability in water-level management and some say over whether their lakeshore should be allowed to drop by as much as 30 metres. In 1964, these lakes were viewed as tools to move goods and produce food and energy. Scant attention was given to them as part of a larger ecosystem. Or people’s lives.

Then there is the water itself. When the treaty was signed, Canada’s stretch of the Columbia contributed about one-third of the water that eventually made it to the Pacific. With global warming and sustained drought on the American Great Plains, it’s now more like 40 per cent. Some scientists think it will rise to 50 per cent before any new deal is inked. Washington State’s agriculture sector alone generates $5 billion a year, largely in part to their recent ability to use water drawn from Columbia River reservoirs.

CHRISTOPHER SWAIN KNOWS ALL OF THIS. He spent 13 months of his life swimming down the river that is born in the heart of the Kootenays, then turned it into a career of clean-water advocacy. Since the Columbia, Swain has swum the entire lengths of the Hudson, Mohawk, Charles and Mystic Rivers, as well as huge swaths of the eastern seaboard. For all of his epic efforts, Swain received the Earth Day Award at the United Nations. Catching up with him via phone at his home in New York, the now 49-year-old is still eager to talk about the river 15 years on. He understands the importance of the treaty more than most of the people who live near the river. The way Swain sees it, Canadians hold all the good cards in negotiations, with the most powerful nation in the world, and they need to play them carefully, this time with the river and its people as the first priorities. “Forget for a minute you have a superpower negotiating [with you] that is going to use all kind of leverage on you,” he says. “Just think for a minute: What do you want? This has to work for Canada and this has to work for the river.”

Bob Keating runs the CBC’s Kootenay bureau in Nelson, British Columbia. He’s been covering the twists and turns of the Columbia River Treaty for years and has a file on the treaty as thick as a phone book (the old ones) to prove it. This is his third feature for KMC magazine.

Bob Keating

Bob Keating worked for the CBC for three decades in Alberta and British Columbia. When he’s not out looking for muck to rake, Keating is a music geek and outdoor lover who, like a lot of Kootenay residents, jumps off the bike in the fall onto a pair of skis.

Related Stories

Don Freschi – The King Of Columbia River Fishing

TV personality and angler Don Freschi was born and raised in Trail, British Columbia, and has fished waterways around…

Eight Minutes in British Columbia

Check out this epic re-edited segment of James Heim shredding BC mountains from Matchstick Productions. Quality action…

Snake River Float Avalanche Airbag Save

This avalanche airbag footage was caught on January 25th, 2012 in the Snake River backcountry near Montezuma, Colo. It…

KMC and Columbia Basin Trust Launch The Headwaters Podcast

This week, Kootenay Mountain Culture Magazine and Columbia Basin Trust launch a new podcast called The Headwaters. The…

Sherpas Drop “Children of Columbia: A Skier’s Odyssey” Trailer Today

Sherpas Cinema, the production house behind Imagination, today released the trailer to their latest film, “Children of…

Columbia Basin Trust Spending $2 Million on 42 Heritage Projects

The Columbia Basin Trust is currently supporting 42 heritage projects around the Kootenay region with over $2 million.…